Stop wasting your customers’ time. Start helping them save it, spend it well – or even invest it wisely.

Most businesses do not think much about our most precious human resource: the time of individual human beings.

Manufacturers, of course, consider time when seeking to reduce set-up, changeover, or cycle times to facilitate variety, customization, or lower costs. Service providers similarly seek to reduce time to streamline activities and increase productivity. While valuable, these internal time-reducing efforts often force customers to spend more of their time, whether on buying or resolving problems afterward. Witness, for example, how companies reduce the time that service representatives spend on the phone by compelling customers to suffer phone-tree hell, waiting to discuss calls claimed to be “very important to us.”

The external effects of time should be of great managerial concern, for customers increasingly place ever more value on their time. (Socially distanced life during the Covid-19 pandemic has only intensified self-examination of how time is spent.) Think about it: customers’ time is incredibly scarce – limited to 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 52 weeks a year – and once consumed, is never to be recovered.

What does anyone do with a precious yet limited resource? Conserve it as much as possible and use it wisely. Companies can create value for customers by eliminating activities that waste their time; saving their time when so desired; offering experiences where time is valued; and even helping customers to wisely invest their time.

No company should impose wasted time on customers. The primary strategic choices today focus on time well saved and time well spent.

Time well saved

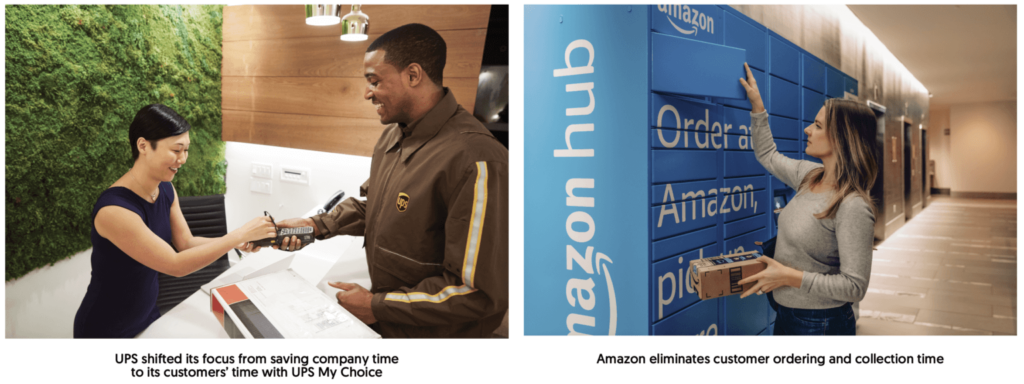

When providing time well saved, many old ways of competing on time work rather well – when, that is, centred on saving customer time, not just company resources. UPS, for example, famously focuses on the efficiency of its drivers and their routes, to the point of mandating that drivers simultaneously start vehicles with one hand while buckling up with the other. Yet recently, the company has shifted focus to its customers’ time, via its UPS My Choice service, which lets customers choose what day and time – for some packages, even where – to receive deliveries.

Amazon excels at saving customer time. It eliminates travel time to and from stores and, through its search and recommendation functions, shopping time itself. It saves customers additional time by remembering credit cards, addresses, and past purchases to avoid duplication and returns. Its one-click ordering all but eliminates checkout time. Prime members avoid the wait for orders that can be bundled into one shipment, while Dash buttons, Echo devices, and Alexa systems even eliminate the time needed to get online to order.

Such relentless focus on saving customer time flows from founder Jeff Bezos’ obsession with customer-centricity. In his 2016 letter to shareholders he wrote: “Even when they don’t yet know it, customers want something better, and your desire to delight customers will drive you to invent on their behalf.” Amazon thus employs new technologies to save consumers time, constantly improving its processes. Meanwhile, its suite of ‘as-a-Service’ business models – Software-as-a-Service, Platforms-as-a-Service, Infrastructure-as-a-Service, and other Amazon Web Services capabilities – save B2B clients the time needed to set up and operate entire businesses. Amazon turned hardware and software goods into services, seamlessly accessible on demand and mass customized to individual company needs.

‘Frictionless’ has become the byword for companies pursuing time savings – reducing their own time and effort, as well as that of customers. It’s one of the pillars of the so-called ‘CX’ movement (Customer eXperience) which aims to make time-saving interactions with customers “nice, easy, and convenient.”

CX works well as a time-well-saved strategy, for when customers want to spend less time as well as less money. However, if a customer seeks time well spent while the company only provides time well saved, the strategy may backfire and result in commoditization. Consider this: when customers buy goods and services from a company as mere commodities – bought at the cheapest possible price and greatest possible convenience – they can turn around and spend their hard-earned money, and their harder-earned time, with companies offering more highly valued experiences.

Time well spent

Experiences offer time well spent to guests, the customers of such offerings. Experiences are a distinct economic offering, as distinct from services as services are from goods. They use goods as props and services as the stage to engage each individual in an inherently personal way.

While experiences offer time well spent, the “nice, easy and convenient” refrain of the CX movement, by contrast, only yields excellent service. Instead of just being nice, experiences are memorable, creating the memories on which brands and businesses become indispensable to customers. Instead of being easy, via a routinization that can make it easy for customers to disengage, experiences reach inside customers to engage them in a personal way. And instead of offering convenience, the ultimate focus of any time-well-saved strategy, distinctive experiences focus on whether customers value the time they spend with the company. If customers spend more valued time, they are likely to spend more money as well – the essence of any time-well-saved strategy.

What, then, makes for distinctive experiences? Experiences are revealed over a duration of time and turn the mundane into the memorable through dramatic structure. The late Jon Jerde, the architect who pioneered placemaking, once emphasized that “what we do is design time… The primary design focus is not an object, but time itself. It’s designing what happens to people in time, in a place” (The Jerde Partnership International: Visceral Reality). Experience-stagers must intentionally design the time that customers spend with them to generate time well spent.

Think of Uber and Airbnb as respective paragons of time-well-saved and time-well-spent strategies. Perhaps one’s first few Uber trips – summoning a car to your exact location, smoothly reaching your prearranged destination, exiting and paying without any fuss – rise to the level of a memorable experience. But after a while, riders recognize that they’re just saving time hunting down a taxi, telling the driver where to go, and paying. It’s all well-designed, but fundamentally offers only time well saved.

In comparison, consider Airbnb and its focus on visiting places – not just the room or home booked, but the locale as well. The company encourages suppliers to act as the ‘host’ for each ‘guest.’ It’s why, in 2013, Airbnb hired Chip Conley, founder of the JDV Hospitality collection of boutique hotels, as its chief hospitality officer. It’s also why, in 2017, it created the Airbnb Experiences platform, allowing customers to book experiences in each place, to help increase the value of time during each stay. And it’s why it so readily shifted into virtual experiences when the Covid-19 pandemic hit in 2020.

Paid-for experiences, such as sporting events, plays, concerts, movies and theme parks – or entirely new genres of experience that pop up in today’s Experience Economy, such as escape rooms, e-sports, or axe-throwing bars – naturally offer time well spent. Service businesses do not. But pursuing the time-well-spent strategy of staging experiences can lift service providers out of commoditization and pay off in increased revenue, customer retention, and marketplace reputation – especially in retail, hospitality, and other industries where customer interactions remain vital.

For example, Zappos, the online shoe retailer now owned by Amazon, offers a remarkable experience through its contact centre. Late chief executive Tony Hsieh banished the industry-standard benchmark of average handling time (AHT), which is a measure of how little time representatives spend on the phone with customers. Zappos instead trains its reps to fully understand and resolve the concerns of each customer, regardless of how much time it takes, to cultivate customers for life and elevate word-of-mouth. The record? Ten hours and 43 minutes!

Contrast Zappos’ relentless focus on time well spent with other contact centres. Their just-as-relentless focus on minimizing AHT throws up barriers to reaching a representative and all too often pushes customers off the phone quickly without fully hearing them out – essentially wasting their customers’ time.

The lessons? Don’t force callers to sift through menu after menu before putting them into a queue to talk to a live human being, or ask them to key in account numbers only to have a representative ask again once connected. Don’t staff checkouts or other interaction points for the least personnel cost instead of the greatest customer demand. Don’t ask customers to fill out forms asking for information already in your system (seemingly endemic in healthcare). Just don’t!

Stop wasting customers’ time

While not crimes against humanity, time-wasters are certainly offences against human customers. The worst thing you can do is waste your customers’ time – yet companies do it all the time.

To stop, first eliminate or at least reduce unnecessary and bothersome interactions. Program or fix systems in order to provide information on demand for individual customers.

Emulate Dr David Feinberg, the former chief executive of Pennsylvania-based Geisinger Health System, who wrote in a LinkedIn post that he would “like to eliminate the waiting room and everything it represents” in emergency departments. “A waiting room means we’re provider-centred – it means the doctor is the most important person and everyone is on their time. We build up inventory for that doctor – that is, the patients sitting in the waiting room.” Geisinger added medical staff and turned emergency department waiting rooms “into clinical space where doctors would actually treat patients – instead of having patients sit in a chair and wait.”

Second, convert badly-wasted time into valuable time well spent, by turning unnecessary interactions into engaging encounters. For example, guests arriving at Vance Thompson Vision in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, receive an iPad to customize their immediate and upcoming non-clinical time. They can watch videos about their forthcoming procedures, read about caring for their eyes, or just play games.

The Walt Disney Company long ago mastered managing guest time, making waiting for rides seem less futile, and even fun. It snakes its theme park lines so that guests can people-watch. It provides “wait time” signs that set expectations it always beats, putting guests in a better mood for each ride. As guests advance forward, they soon encounter pre-show vignettes for the ride experience, creating anticipation. And it cuts down the time spent actually getting on a ride to the bare minimum through a continuous boarding process; rides never stop, as guests get off on one side and new guests get on the other.

More recently, Disney has developed mobile apps which promise to “turn wait time into play time,” offering interactive games, trivia, music and other activities for those attractions with the longest waits. These will also, over time, offer more ways for guests to interact with park experiences, as with the Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge attraction.

Eventually there will be little if any physical queueing, as guests walk smoothly from one scheduled experience to the next, where experiences include not only rides and restaurants but character interactions, alternate reality games, smartphone-based activities.

Such options layer time well spent upon time well spent.

Charging for time well spent

Customers aren’t stupid. Time is money, as Ben Franklin famously quipped. Wasting their time detracts from the overall value provided. As a result, they will demand a lesser price to make up for supplying wasted time. In effect, this effectively compensates customers for the time wasted in the form of a discounted price. It’s the cost paid by companies for wasting customer time.

In contrast, when customers save time over what they can get elsewhere (or do for themselves), they come to value such offerings more highly – and pay in kind. Whether selling commodities, goods, services, or experiences, think of it as:

Money charged = Functionality provided + Net value of time

Time wasted has a negative value, time well saved is essentially at zero, and time well spent has a positive value.

When customers desire only “nice, easy and convenient,” it is fine to provide exactly that. But when they desire time well spent, the value of that time is much higher to them than that of time-well-saved offerings. That yields premium pricing.

There’s one foolproof way to know if experience offerings are worthy of customers’ attention and valued as time well spent. They willingly pay explicitly for the time spent, whether it’s through an admission fee, membership fee or some other form of time-based payment. No one would imagine going to a movie, a sporting event, a concert, play, or theme park without paying an admission fee. These offerings are instantly recognized as experiences offering time well spent. And because people do value their time so highly today, companies far from these traditional fee-commanding industries also now charge admission, including leaders in retail, restaurants, manufacturers and myriad new genres of experiences.

The money value of time

All current and potential experience-stagers should examine their offerings by the resulting ‘money value of time,’ or MVT. This metric recognizes that the amount of money customers willingly pay for any experience is directly proportional to the value they receive from the time they spend. Their spent money becomes a proxy for the degree of time well spent in any experience. This has several implications. One, if there is no charge for time, people will naturally come to assume that such offerings are probably not worth experiencing. Two, the more time well spent, the more money customers should be willing to pay. And three, offerings commanding a fee can measure the experience against others – and with itself over multiple periods – on the MVT scale of expenditure per minute.

Movies provide perhaps the most common (pre-Covid) experience. With ticket pricing across the world generally between US$8 and $15, assuming $12 as an average price and two hours as an average length, movies generate about 10¢ per minute. Time drinking a Starbucks cup of coffee can run about the same. (An even better measure would include revenue from memorabilia, parking services, food and drinks, in the equation, but these figures are not generally public).

Use this MVT as a baseline index. How much is your experience worth? If you can charge around 10¢ per minute, congratulations, you’re staging a good experience, one on par with a successful movie. Netting more means an even better experience; getting less maybe just a so-so experience.

In the so-so bucket? Enhance your experience-staging prowess. Doing better than a movie, or Starbucks? Don’t rest on your laurels. Competition always intensifies and customer expectations continually expand. (Witness the production values in today’s movies compared to just a few decades ago). Disney theme parks have MVTs of around 20¢ per minute, but escape rooms, Instagrammable places such as the Museum of Ice Cream, and immersive art experiences such as those created by Meow Wolf now garner 40-50¢ per minute, or more.

Time well invested

One can offer even greater value than time well spent. How? By helping customers to achieve their broader aspirations, whether via the proverbial “life-transforming experience” or, more likely, through a series of experiences that effect desired change in some significant way. In our book The Experience Economy we simply call such economic offerings transformations – where companies use experiences as the means to guide customers to achieve some particular change.

Transformations – think fitness centres, healthcare, education, consulting, coaching of all stripes – can enrich people’s lives. But companies can’t do it alone. As the old saying goes, you can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make it drink. Customers – whether consumers, businesses, or employees – have to undergo the transformation for themselves, whether doing workouts, following a wellness routine, completing homework, or following counsel or coaching instructions.

That’s why transformations offer time well invested. Under the guidance of their transformation elicitor, customers invest their time, aiming to achieve their aspirations and reap dividends now, and in the future. With time well invested, it matters less what inputs the elicitor provides; the main concern is the outcome customers achieve. Indeed, the customer is the product – it is a changed dimension of being that they seek. Therefore, in offering time well invested, companies should not merely charge for well-spent time, but for the demonstrated outcomes that customers achieve. Channelling Ben Franklin again: industries that help people become healthy, wealthy, or wise, in particular, should shift to outcomes-based compensation. A few companies lead the way.

Beyond just the money value of time, enterprises guiding transformations should focus on the compound interest of time well invested. When helping a person become healthier, wealthier, or wiser, companies are helping individuals spend their precious and finite time more wisely, from greater wealth, in better health.

It’s about time

In today’s Experience Economy the locus of competition is shifting to time: not only the time customers have and want to spend, but also the time of employees. Their time, too, can be wasted, saved, spent and invested.

Whether you become commoditized or create the circumstances to thrive depends on your view of time and how it’s consumed. Will you merely provide time well saved or stage time well spent? Or perhaps even guide time well invested? It’s time to make your strategic choice.

B Joseph Pine II and James H Gilmore are co-founders of Strategic Horizons LLP and authors of several books, including jointly The Experience Economy: Competing for Customer Time, Attention, and Money and Authenticity.