The paradigm has changed. Leaders need to rethink strategy from first principles, argues Tony O’Driscoll.

Over the past quarter-century as a business school professor, I have almost invariably begun courses with one simple question: “Why do firms exist?” Equally invariably, students respond: “Firms exist to make money!” When I ask, “But what happens if I spend more money than I make?”, their response rarely deviates from the amended viewpoint: “Firms exist to make a profit!”

The business world has been transformed over the last 25 years, yet students’ answers have barely evolved. It is a sign of the deep need to rethink the role of strategy to reflect the new realities of a more connected ecosystem-based world.

Traditional strategy

The traditional approach to strategy was profoundly shaped by Milton Friedman. In 1970, he wrote that the responsibility of corporate executives is to “conduct business in accordance with the desires of shareholders,” namely, “to make as much money as possible while conforming to the basic rules of society.” Business’s only social responsibility was “to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase profits as long as it stays in the rules of the game.”

The perception that firms exist only to make money for shareholders has burrowed deep into our collective consciousness. Indeed, on the rare occasion that a student deviates from the norm in answering my question, it is typically to argue that firms exist to create value for shareholders. That is the point at which I introduce the concept of business strategy, defined as the formulation and execution of an integrated set of choices that create, deliver and capture differentiated value. But how are those choices conceived?

Ego-centric and eco-centric strategies

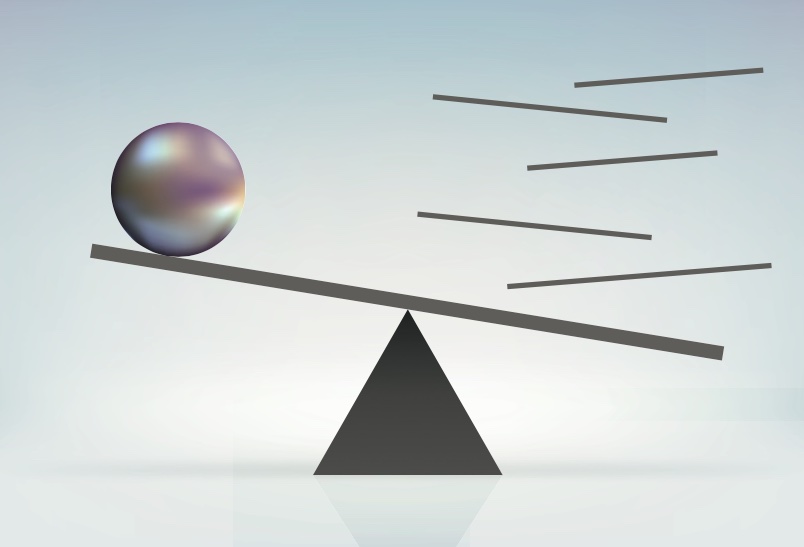

If firms only exist to create shareholder value by generating as much profit as possible, the strategy of each player (or firm) in the business game is obvious. Defeat other players by seizing control of the most profitable position in the value-chain and defend that position to maximize their own value-capture, taking it away from other players until they are squeezed out of the game. In this zero-sum, ego-centric framing of the business game, the core strategic objective is to win by defeating rivals.

But does this strategy actually create value-add? Are we not just fighting for the biggest slice of the market in a given industry pie? Peter Drucker argued that the purpose of business is to “create and keep a customer.” This stakeholder-based perspective enables us to imagine a fundamentally different future: to focus on growing the size of a given industry pie, or on collaborating to bake new pies that customers value. The value-generation game is changing.

In an ecosystem-based game, the strategy of each player is to remain relevant and useful to other players in order to sustain the overall health, resilience and development of their shared environment. In this positive-sum, eco-centric framing of the business game, the core strategic objective is to win by ensuring that all players remain motivated to play the shared value co-creation game.

This represents a complete paradigm shift – not only in what strategies we pursue, but how strategy is developed and executed. Research has shown that over 75% of strategies fail today, which is for two key reasons: their underlying premises, and the mechanisms through which they are executed, no longer fit reality. Today, strategies are typically formulated at the top of the organization. A profitable position of sustainable competitive advantage is identified and strategies to secure that position are developed. They are cascaded down the corporate hierarchy and employees are commanded to implement structural, procedural and technological changes as required.

The flaws in this approach are two-fold. First, in a world as complex and unpredictable as today’s, the assumption of sustainable competitive advantage no longer holds. Rita McGrath has taught us that organizations can no longer survive by competing within existing industry boundaries: instead, they must enter new cross-industry arenas, or ecosystems, where they vie for resources by helping stakeholders with control over these resources to create added value. In such a world, competitive advantages are transient, so it is crucial that we develop an empathetic understanding of customer needs. We also need to enable cross-ecosystem teams to emerge around value-creating opportunities. In short, strategies must become less ego-centric and episodic, more eco-centric and emergent.

Second, even if well-conceived, the execution of strategy typically falters due to human resistance. Organizations do not change unless people change, and people won’t change unless they see personal value in doing so. Those required to implement strategy are rarely involved in formulating it, so they have no intrinsic motivation to change. This too needs to change.

Strategy’s rightful place

This is the new paradigm: collaboratively designing strategies that create shared value, and collaboratively delivering those strategies to capture and distribute value. Our approach must be radically reconceived to maintain fit with an ever-evolving business ecosystem. To put strategy in its rightful place, begin by clearly articulating your PVAC:

- Purpose – Why do you uniquely exist?

- Values – What do you fundamentally care about?

- Aspiration – What do you collectively aspire to achieve?

- Complementors – Who has similar aspirations and complementary capabilities?

Once your organization’s PVAC has been established, strategies simply become the dynamic and integrated set of decisions and actions required to operationalize it. Straightforward as this sounds in summary, it means a wholesale shift in the strategy paradigm. We must move from ego-centric and zero-sum, to eco-centric and positive-sum; from shareholder to stakeholder value; from corporate profitability to customer empathy; from value-capturing industry position, to value-creating arena partnerships; from sustainable competitive advantage to sustained collaborative advantage; from sequential formulation and execution, to dynamic design and delivery; and from top-down mandated change, to edge-back motivated change.

Business can – must – become a stronger force for good in the world. As academic and business consultant Clay Christensen taught us, revolutions in the business zeitgeist come slowly, then suddenly. We will know the revolution is on its way when students respond to my trusty old question with the answer that “firms exist to engage in ecosystems that create and maintain shared value-add for all stakeholders while relentlessly focusing on the needs of customers.”

I hope that moment comes sooner rather than later.

— Tony O’Driscoll is a professor at Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business.