Teams have become the atomic unit of work. To realize their potential, leaders must learn how to coach.

Implicit in the idea of teams is a promise: together, we can achieve more than we could as individuals. In healthy team contexts, diversity of knowledge, skillsets, and perspectives can all be harnessed to achieve what was seemingly impossible alone.

We witnessed this on 18 February 2021, when Perseverance, the Mars rover, travelled more than 300 million miles through space to arrive on the Red Planet. The robot rover’s touchdown was an amazing feat of science, teamwork and leadership spanning years of research and work. There may have been 50 people in Nasa’s control room at the time of the landing, but the actual team numbered more than 1,000. It comprised scientists and engineers from varied disciplines, countries and organizations all around the world. When everyone cheered madly, it was because of the wild success of an audacious team.

Adam Steltzner, Nasa’s chief engineer for Perseverance, notes in his book The Right Kind of Crazy that there is no one person who can do the lion’s share of the work. Teams require 100% collaboration and cooperative effort. To achieve something as incredible as the Mars rover landing, you need a group who can operate, collaborate and innovate under pressure.

While your team may not be dealing with Nasa-level goals, you’re probably being asked to take on more complex problems, operate under uncertainty, collaborate across more boundaries, and act with increasing speed. All of these demands are fundamentally changing what is expected of teams, how people cooperate on teams, and what it takes to lead a team.

Teams have become the most pervasive – the atomic – unit of work in organizations. Externally, it is only through teams that complex strategies can be fully implemented, innovations emerge, and change happens. Internally, teams are the site on which company culture meets the real work, shaping the employee’s everyday experience.

Employees’ expectations are also shifting quickly. People want more engagement and inclusion, and faster, focused development. From the patterns we see in conversations with chief executives, chief people officers, and current and former students, it is clear that workers want and expect more humanity from their work. Employees want to feel like they matter; they want to contribute, learn and develop, both as workers and as people. They long to be part of a team that provides the meaning, challenge and security necessary to become their best selves and accomplish great things.

These market and internal forces have shifted what’s required and needed from team leaders. Today, team leaders need different tools – they cannot rely on positional authority and technical expertise to create a winning team. Instead, they need to reimagine their role as a coach.

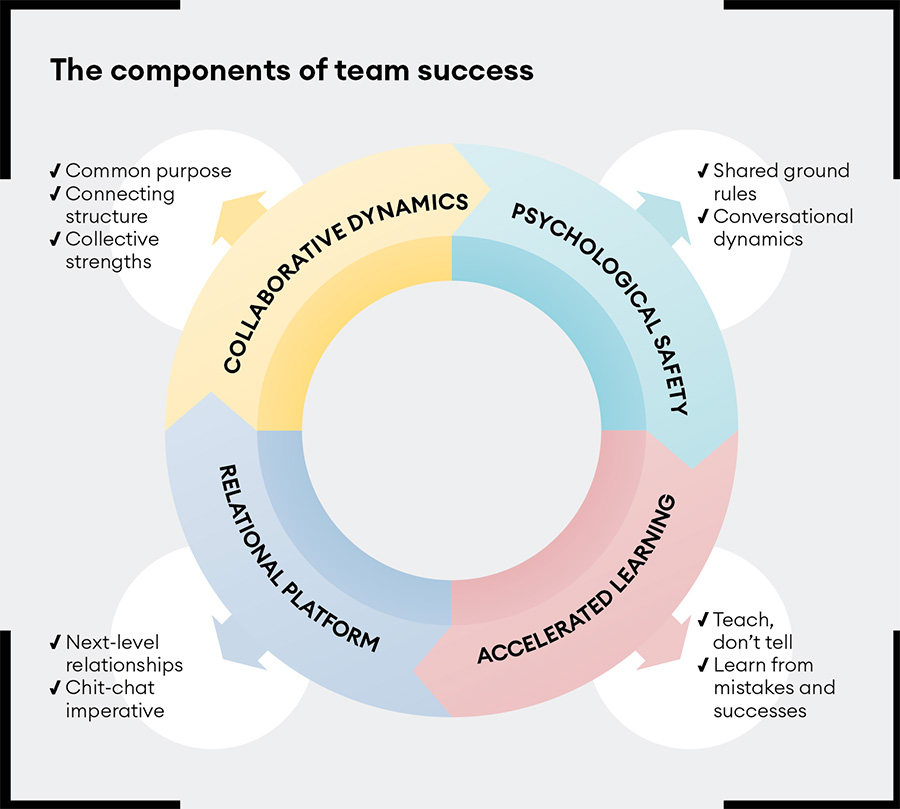

At Duke CE, we are pleased to have partnered with ExecOnline to reach more leaders through a course on team coaching, part of a wider series on coaching. We have identified four key domains of team success for leaders to focus on as coaches:

- Fostering collaborative dynamics

- Building the relational platform

- Ensuring psychological safety

- Accelerating learning and adaptation

While our online course covers all of these aspects, this article will focus on the fourth domain: accelerating learning and adaptation.

Accelerating learning and adaptation

In some ways, the goal of all coaching is to accelerate learning and adaptation. But in today’s world, and for today’s leaders, we suggest that there is a specific way to accomplish this objective: create learning and enrichment opportunities in real-time, every day. When time is tight and the stakes feel high, a leader’s natural inclination is often to just get the work done. The leader becomes controlling, telling others what to do, or just doing the work themselves. (Does this sound familiar?) The result is that both the leader and the team miss out on a learning opportunity. So how can you turn everyday challenges in your work into development opportunities?

To gain insight into this question, a team at Duke CE sought out organizations that demonstrated the capability to accelerate development and deliver high-quality results while under pressure to deliver. They wanted to parse the key factors that made those organizations successful in these particular ways.

A benchmark example was the innovative and powerful learning environment at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. Working with Dr Charles Wiener, MD, professor of medicine and physiology and president of Johns Hopkins Medicine International, Duke CE learned the four foundational principles of Hopkins.

1 Problem-based learning uses real-world problems as an opportunity to develop critical-thinking and problem-solving skills. At Hopkins, they use ‘rounds,’ during which doctors visit patients in the hospital, as the immediate context and material for development. During rounds, young doctors are given the chance to explore the nuances of a medical case with the guidance of a more senior physician. In this way, rounds create a habitual, daily touchstone for exercising meaningful problem-solving skills in an environment safe for exploration.

In a business context, our daily, habitual touchstone encounters might be our morning meetings, weekly project updates or customer-client visits. These meetings are probably necessary to the functioning of your organization; are you leveraging them to maximize learning opportunities and growth? Are you exploring hypothetical situations and encouraging everyone to speak? Activating the learning mindset of your team starts with the kinds of questions you ask around the table.

2 ‘Teach, don’t tell’ is a method of teaching based on the Socratic method. It calls upon senior, experienced doctors to use questions and inquiry to teach, rather than simply providing answers. Instead of instinctually providing a diagnosis or opinion, experienced doctors have to ask probing questions and, importantly, listen to gaps in understanding. The Socratic style of questioning not only increases understanding and promotes self-discovery among medical students and young doctors, but provides an immediate feedback loop for the students’ own understanding.

This method, long-known and widely utilized in medical settings, is underused in business. The team leader can and ought to ask questions pointed toward problem-solving, aiming to point out gaps in the communal understanding of an issue. Teaching in this manner pushes the leader to be a better coach, empowering individual thought and ideas. This, in turn, accelerates both individual learning and group understanding. As one manager in one of our client organizations said, “Not only does the ‘teach, don’t tell’ method deepen team learning around specific customer challenges, but it also allows a team to explore issues more thoroughly, possibly unearthing previously overlooked errors and incorrect assumptions.”

To use this method in practice, try using these coaching questions:

- “What have you tried thus far?”

- “What’s working? What’s not?”

- “Is there a different way we could frame the problem?”

- “Do you have all the data?”

- “What assumptions are you bringing to the problem?”

- “Who does this well? What would she do?”

3 ‘Point of the wedge’ is a metaphor used at Hopkins to describe the position of the junior member of the team – typically an intern – with responsibility for an individual patient’s care. This person stands at the apex of a large team of professionals dedicated to achieving quality patient care, and to the learning and development of the individual at the point. In the hospital setting, this wedge comprises attending physicians, residents, medical students and nurses. They are available to provide support to the point of the wedge and observe progress from a distance, to ensure patients are receiving quality care. Importantly, however, the day-to-day responsibility for delivering quality patient care always falls to the junior member of the team.

Contextualizing this in the business world means pushing responsibility and accountability to the most appropriate less-experienced team member in order to help them develop and own outcomes. As team leader, our natural instinct is to assign work to the most experienced team member or to the person occupying the role naturally encompassing the work. Overcoming this instinct and appointing a less senior or less experienced team member as the point of the wedge, and pairing them with a more senior person, can accelerate learning and development. The ‘point’ is responsible for preparing rigorously to address the problem, or make the presentation, or handle the client. Once the point has presented their views on the issue, a structured discussion ensues, in which guided inquiry is used to deepen the point’s learning and, in many cases, the full team’s. In our work with clients, we’ve found that less-experienced team members felt a strong sense of accountability and enthusiasm for their work as a result of being positioned as the point of the wedge. They often expressed excitement over the opportunity to take on additional responsibility and showcase their skills to their teams.

4 “We learn from our mistakes” is the final principle at Hopkins. Errors and near-misses happen, but should be reframed as opportunities to improve, not to assign blame. After-action reviews (AARs) are the natural locus for reflection in a business context, but what constitutes a good review? In her work with the military, Sanyin Siang learned about two key principles used by the US Special Forces for effective AARs.

First, remember that there are multiple perspectives operative in a single team. Each comment made by a teammate comes from their own unique point of view. Everyone has a perspective to share; everyone has a different role to play. When reviewing an action item, take time to hear the perspective of every person in the room. The most junior member of the team might lack certain information, but he may also notice patterns of behaviour that senior members are blind to. Senior team members might not have a hand in every detail of a project, but they might be able to provide context for everyone’s individual work.

Second, foster an environment in which everyone is encouraged to speak up, regardless of where he or she stands in the hierarchy. The US Special Forces spend intentional time building culture that promotes speaking-up. Everyone has permission to critique others – if you see something wrong and bite your tongue, you’re not doing justice to the organization. Instead of focusing on blame, though, each person is encouraged to frame an action around what should be replicated and what should be improved. Then, to apply what they’ve learned in an AAR to the next mission, teams take the time to perform a pre-action review, ensuring that past learnings are in the front of everyone’s mind.

From the military, from medics, and from a groundbreaking mission to Mars: these insights point towards a very different future for how teams work. Like businesses today, today’s teams are having to learn how to run faster and adapt in briefer and briefer cycles. They don’t need captains who are only capable of running a pre-determined play. Instead, they need more team leaders who think and act like team coaches, who are capable of developing a play as it evolves, and who can draw on the very best in their people, to deliver the exceptional results our organizations need.

Sanyin Siang is executive director of the Fuqua/Coach K Center on Leadership & Ethics (COLE) at Duke University. Michael Canning is global head of new businesses at Duke Corporate Education.