The world’s largest democracy holds tremendous opportunities for business – if you know how to navigate the country’s nuances.

India spelled opportunity for Western companies when their own markets were shrinking. Business has shifted eastwards since 2000 and the trend has accelerated after the global financial crisis of 2008. India is one of the oldest civilizations in the world and is a complex mixture of new and old, a confection of West and East. With a strong and stable democratic political system, a young nation where more than 50% of the population of one billion is under 35, a pervasive entrepreneurial spirit and high domestic demand, the country has much to offer. Indians are known to be self-reliant, and have great capitalist spirit. Many of the world’s top billionaires such as Mukesh Ambani, Lakshmi Mittal and NR Narayana Murthy have created best-in-class companies. That being said, like any country, India has specific cultural issues which incoming businesses need to consider. Let’s consider some of these.

Liberalization, privatization and globalization

After gaining independence from British rule in 1947, India became a republic in 1950 and began developing its economy. It has focused primarily on import substitution – unlike many developing nations, it has a strong home market – and exporting. For the first four decades after independence, businesses operated under what was called the ‘Licence Raj’ system, meaning that companies were given licences by the government, to allow them to operate.

This was a fairly protectionist stance and companies survived despite being unproductive, inefficient and without competition. However, in 1990, the government changed its approach and opened the country to so-called ‘LPGization’ – the liberalization, privatization and globalization of the Indian economy. This move drove domestic companies to become more global in their outlook, and to start competing with Western multinationals and making products that were acceptable beyond Indian borders. Many young Indians who had settled overseas came home in a wave of reverse brain-drain, armed with new business ideas. Indians are great entrepreneurs.

Hierarchy and inequality

Sociologists would call India a nation with a high power distance index (PDI). PDI is not about the absolute levels of inequality, but the degree to which the bottom (and top) echelons accept and expect inequality. This contrast – and acceptance – can be seen with homeless families living under sacking on the pavements of Mumbai outside the 27-storey, $2 billion home of billionaire Mukesh Ambani. Mumbai is a city of 20 million people, where many have a monthly income of less than $150. When doing business in India, you must understand the scale of inequality.

Indians have also embraced old British customs of hierarchy and there is high degree of formality between colleagues. It is common to call a superior ‘sir’ or ‘madam’. Similarly, influences of Hinduism and caste have created a culture that emphasizes established hierarchical relationships. All relationships therefore observe hierarchy. The idea of hierarchy is deeply rooted in the Indian psyche. Hierarchical relationships are important in the business context.

Working ‘through proper channels’ is highly emphasized. For example, if you are looking for a quick result on some licence application, take time to study the hierarchical set up of the office to which you’ve submitted it. If you respect the office hierarchy, your work gets done faster. Students call teachers ‘guru’ and at work ‘the boss’ is considered the ultimate source of responsibility and power. Hierarchical relationships mean bosses tell subordinates what to do and how to do it, and seeking permission from those above is a sign of respect. In India, bosses are like benevolent dictators who look out for their teams.

Family means business

Hierarchy also shows up in families, where the father is considered the patriarch and head of the family. Family ties bind India – just observe the crowds gathered outside airport gates to greet returning family members. Indians rely on family for everything, from arranged marriages to buying a home and naming a child. The elders are normally consulted before making important decisions and approval is vital. If a decision is made despite disapproval it causes unease in the family. For example, the Ambani brothers engaged in a well-publicized feud after their father’s death, until their mother stepped in and settled it. It is common to see several generations of families living under one roof and this makes relationships critical – in life and in business.

The family-owned company structure can be a challenge to doing business in India. From the small street-side vendor to the large multinational, many Indian firms are still family-owned. The larger ones are referred to as ‘promoter-owned’ companies and while the ‘promoter’ may not be the majority shareholder, he or she can act as wished on behalf of other shareholders. It can be difficult to know who the real decision makers are, as titles like group president or managing director can mean little. While this is changing, as companies become listed and subject to new rules of governance, it is still worthwhile investing time in identifying the real decision makers.

Bureaucracy, red tape and rules

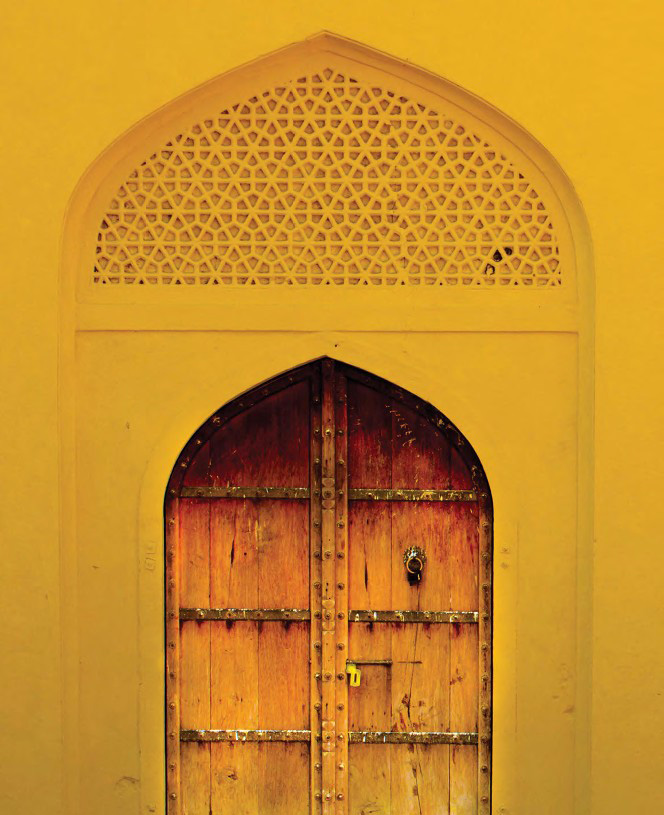

For all the ‘India shining’ hyperbole, there are lots of pockets of success and plenty of impediments. There is a joke in India that you can bring proceedings to court and your grandchildren will inherit them. The regulatory framework has been tight in some industries such as banking, which actually stood the country in good stead during the 2008 financial crisis. However, not all aspects of the legal system offer business a level playing field. Contracts in India are not to be taken literally. Indians believe everything happens for a reason, which is a significant factor in its decision-making process – it is slow and people with a lot of authority typically reach final decisions.

Delays are frequent, especially when working with the government. Recently I took my son to watch one of the two Indian stops by the solar-powered aircraft on its maiden voyage across the globe. There was a lot of fanfare and media coverage, but a week later, the plane had still not departed. While people were blaming the rain – which only fell on one of the days – the genuine reason for delay was the long and arduous process of completing the paperwork, which threw out the entire schedule. The tax authorities can take a year to reply to queries. And while parts of the country have world-class infrastructure, others still struggle to get good power connections and airport connectivity.

Nikhil Raval is managing director of Duke CE, India.

An adapted version of this article appeared on the Dialogue Review website.