The nonprofit sector has long understood how to engage people and motivate them to work for free. Here’s what business leaders can learn from volunteer work about how to spark employees’ passion.

Imagine if every December you had to recruit, motivate and organize 7,000 volunteers working in two-hour shifts to sort, wrap and correctly tag almost 67,000 holiday presents for kids – a specific present requested and delivered to each specific child. And that’s after having collected, assembled and distributed close to 15,000 back-to-school backpacks just a few months before. Queen Elf of Family Giving Tree, Jenn Cullenbine, and her team do this year after year. They are so successful at getting people to donate their time, effort and money, that Cullenbine actually has more volunteers every year than she can use.

Alternatively, imagine you were responsible for constructing a new church building, but had little money to pay for most of the work on the $3 million project. Yet, you still managed to get it built on time, on budget and with half the labour coming from people who didn’t even belong to your congregation. Reverend David Bradbury of the Anglican Church did just that.

How do these leaders get people to work hard, doing what needs to be done, in their personal time, repeatedly and for free when many managers cannot even coax their paid employees to do the jobs they were hired for?

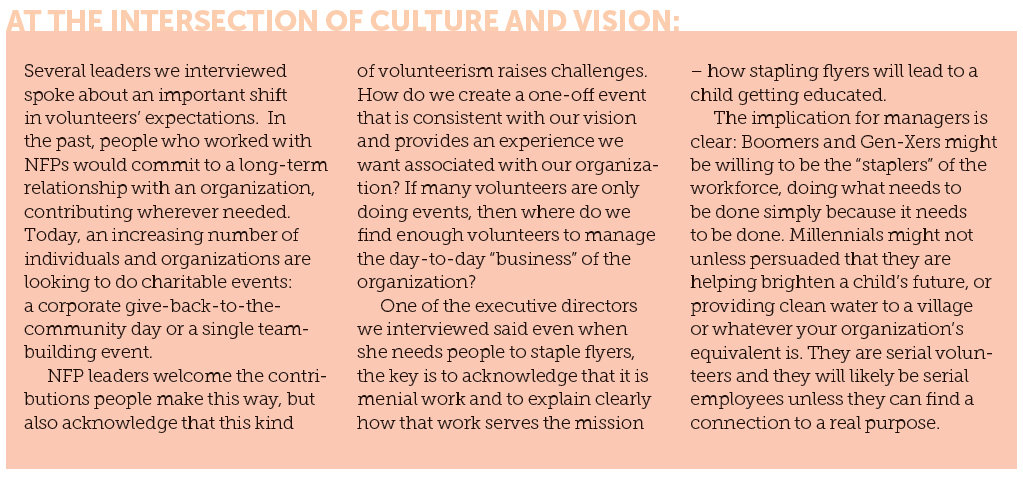

More and more, we hear from middle and senior managers that their younger employees act like showing up and working is doing the manager a favour, as if they are volunteers. These managers are finding it harder to motivate and focus their teams than it was 10 or 15 years ago. They are paying these employees, offering good benefits packages, and yet the employees give little discretionary effort.

What are people like Jenn Cullenbine and Reverend Bradbury doing to inspire enthusiasm, labour and loyalty? Not-for-profit organizations (NFPs) rely heavily on volunteers (people who are not paid or who are paid relatively little for their time and effort) to accomplish their mission. If NFPs cannot attract, retain and use their volunteers well, their organizations fail. We decided to ask these leaders for their advice on managing and engaging volunteers. We believe these same strategies also work well in a corporate setting.

We interviewed a varied set of people around the world who work in the NFP sector. Most also volunteered with one or two other organizations. So, what should Gen X and Boomer leaders be doing more or less of, if they want to manage Gen Ys (and all their other employees) more effectively? A combination of culture, leadership and day-to-day management makes the difference.

Culture: create the experience

As leaders, we have the ability to shape the culture in which we and our teams work. The environment we create communicates our values, sets a tone for behaviour and attracts or repels people. Think about a situation you have been in where you checked your watch every few minutes, feeling oppressed and put upon, wanting desperately to leave, but feeling obligated to stay.

Now, think about a situation where the time flew past, where you were stimulated by the people you were with and what you were accomplishing. Which environment would you rather visit and spend time in regularly? Which would your team members want to spend their time in?

Those who manage volunteers successfully concentrate explicitly on creating the experience. They think about the physical environment that they bring people to. They consider how best to express the mission and outcomes – that is, what the volunteers’ efforts will accomplish – and make sure the volunteers understand what the experience will be like. They try to make the people feel welcome, valued and useful.

Volunteers’ roles have to fit what they want from the experience. A former CEO of an organization running support centres for the homeless noted that feedback and connecting people to the right tasks is essential. She told us about a volunteer in another NFP who had worked on an arts campaign. The volunteer had been a teacher, so the staff gave her a project relating to arts education. After a week, the CEO checked in with the volunteer. The volunteer revealed that she had been away from education for some time due to health issues. She indicated that she had really preferred to be doing administrative tasks. The CEO made the job shift and the volunteer thrived. “She had the place shipshape in no time.” The volunteer was able to make a difference in a way that matched the experience she wanted.

Another way to shape the experience is to set clear expectations and standards. We heard from several of our interview subjects that they negotiate a “volunteer agreement” with people, setting out what the volunteer will do and by when. The NFP staff support and train their volunteers, then trust them to do the work. They allow autonomy where possible, check in periodically and set people up to succeed in the tasks. Flaminia Mangone noted that The Nature Conservancy has volunteers working side-by-side with paid staff, even when doing hands-on controlled burns in forests. Those volunteers are trained just like full-time staff and are expected to act safely and appropriately during that experience.

These NFP leaders strive to create a culture that values accountability and results. People must want to be there and feel included. And, they also need to know that there are standards to meet. As one interviewee noted, when she herself volunteers, “the staff takes it seriously, so I feel I should as well.” The people who come to work with those organizations know their efforts have a positive effect and are pleased to be part of something great. They are looking for an experience where they can use their skills (or learn new ones) to make a difference.

The cultures that attracted and retained their volunteers were ones where the managers respected people and the time they were offering. The cultural values mirrored the organization’s mission, and promoted dignity and respect for those involved. The leaders explicitly focused on the experience they were creating for all stakeholders: is it a positive one? Does it meet people’s needs for being in a group, or growing as a person, or making a difference or feeling heard and touched? Were the volunteers’ skills used well and efforts appreciated? Were they greeted with a smile and a hello, or instead did the manager just bark orders at them?

Leadership: share your passion

People want to be part of something meaningful and they want to be part of a winning team. “Of all the events that engage people at work, the single most important – by far – is simply making progress in meaningful work,” noted researchers Amabile and Kramer in their 2011 New York Times opinion piece. People look to their leaders for inspiration and direction – where are we going and why?

In the NFP sector, a critical piece of advice was to have a clear vision and communicate it well. Be sure to communicate where the project or organization is on the path, what the end state looks like and why it matters that they succeed. Remember Reverend Bradbury, the leader who led his parish’s efforts to build a new church? It started out just as a new church, but morphed to include community space and meeting rooms. It was built in two years, on budget and almost entirely by volunteers, many from outside his congregation. He cited two factors that helped: first, he went around to community groups, told them what the project was and asked for help. He shared the vision and how the project would fit into their community. Second, at the end of each project stage, they had some form of a celebration. They recognized where they were and reaffirmed where they were going. These events provided an opportunity to remind people of the vision, their role and what to do next. The events were a way for Reverend Bradbury to share his energy and focus.

Leaders who can connect the work to a larger vision help people feel engaged. Lisa Wardle twice worked for the organizing committee for the Olympic Games. For the 2002 Winter Olympic Games, they had more than 20,000 volunteers working long hours on a fixed schedule over three weeks. They directed traffic, took tickets, hauled trash, operated elevators or other such jobs – for hours and hours at a time. Sometimes those volunteers were standing out in the cold for those long shifts. In exchange, they got free burgers, pins and a watch. Yet, those Games had zero attrition in volunteers. Zero. She credits the clear, simple vision set for those games: “Best Games ever.” That vision set the positive, aspirational tone for all the leaders, all the staff and all the volunteers.

Communication about the purpose is essential. The other part of leadership is sharing your energy and passion about what you’re doing. Passion is contagious, just like laughter and yawns. We spoke to an executive director who said after he listens and asks questions to understand someone’s interest in volunteering, he then explains why he got started in the NFP sector and what he loves about the community he serves.

We spoke with others who shared similar stories, including a gentleman who as a young man spent two years on a Mormon mission to an American Indian reservation. Seeing people who were truly in need led him to a career where he could help change people’s lives for the better. He did that work for 37 years, ending his career as head of a large humanitarian aid organization. Sharing their purpose and the passion driving them helps these leaders connect to others and get others excited to join the organization’s work.

Build a relationship and grow together

Many of us have been lucky to encounter amazing leaders – these are leaders who others point to and say, “I’d follow that person anywhere,” and they mean it. It comes down to establishing a strong relationship: sharing a vision and understanding what role that other person can and would want to play.

Relationship management is a core leadership skill. In order to match people to roles and create the experience they’re looking for in a way that meets the organization’s goals, a leader needs to know his or her team. They need to connect as people, not just as role-fillers.

Our NFP experts made it sound simple: ask people questions and listen to their answers. Ask why they want to volunteer. Ask what they would like to do or try. Ask how it’s going. Ask what they have seen elsewhere that might work here. Then, pay attention and listen to the answers. When an executive director was new to his community, he met with Sarah (one of his staff ) about holding a young leadership programme. Having run them before, he laid out his plan and asked her what she thought. “That won’t work here,” she said. He replied: “Okay, so how do we make one that will?” Together, they reshaped the approach based on Sarah’s input. Strong relationships rely on feedback going in both directions. Our experts advised to find out from the people doing the work what is going well and what else might be needed.

We heard over and over that many volunteers are there to learn new skills or to get to practice existing skills. So, the better-run NFPs offer training to staff and to volunteers. They help their people try new activities and support and coach them as they learn. Not coincidentally, getting to develop skill mastery and grow additional skills are two features of motivation and engagement, as Dan Pink explained in Drive and large-scale engagement studies have found.

Providing opportunities can be a great recruitment tool as well. A distinguished giving director related how she “recruited” one of her best volunteers: she was having dinner with a friend. Her friend’s brother came by, but was preoccupied, having heard that a colleague had been diagnosed with breast cancer. The director, herself a survivor, invited the brother to a planning meeting for a cancer-related fundraiser. He came and joined a logistics committee. The next year, he asked to take a lead role, even though it would require public speaking. This man was an introvert who sat behind a desk at his regular job. But he knew he’d get advice and support whenever he needed it. He did so well, he won a volunteer award. After three years of trying new roles and gaining fresh skills as a volunteer, the man decided to buy his own business, something he never could have done before. Due to the training, growth and support the NFP offered him, he is a committed and now more skilled volunteer who is there for the Giving director, for whatever she needs whenever she needs it.

The director allows people to try doing what they are not initially qualified for, ensures they know that they have whatever support they need to succeed (and then really does provide that support to them), recognizes and rewards their achievement and builds a relationship over time. A final piece of advice was to let people know you appreciate them. Recognize what they’re doing and the contributions they are making. This is a particularly powerful opportunity for the leader to do something that blends all three principles outlined in this article:

● Acknowledging achievement, effort and contribution is an important part of a culture – it demonstrates the leader’s and the organization’s values and enhances the workplace experience

● By connecting the thanks or praise to the “why” of the organization, leaders can reinforce the vision and their own authentic passion for it. Say something like “I want to thank you for _____. It has added significantly to our ability to fulfill our mission of ______.” Linking thanks to outcome deepens the mutual commitment to the mission

● Appreciation strengthens the parties’ commitment to one another, provided that the form of recognition is aligned with the recipient’s desires for recognition.

All of the advice from our NFP leaders seems straightforward: give people meaningful work, in an environment they feel comfortable in, with a chance to learn, grow and be treated with respect and appreciation, and on a team led by an energizing leader who communicates vision and goals clearly. Anyone who works chooses how much discretionary effort to give. People choose whether or not to share a new idea, or work a little faster, or help another team member. In that sense, all managers are leading volunteers, even those who get a paycheck. Acknowledge that, apply the lessons from our NFP experts and see how much more engaged your people will be.

Marla Tuchinsky began working with Duke CE in 2002 and is involved in delivering executive education strategies and programs for corporate clients. Thomas Hughes is member of Duke CE’s educator network and an organization development, learning and development consultant.

An adapted version of this article appeared on the Dialogue Review website.