In order to foster deep engagement in your organization, you must demonstrate that humans are more important than rules or bureaucracy.

Leaders and human resource professionals understand that an engaged workforce is good for both productivity and a better quality of work. Despite this widely accepted and oft-proven principle, many organizations fail to do what is necessary to surpass conventional engagement and achieve a state that we call “deep engagement.” When individuals are deeply engaged, they feel a genuine emotional attachment to their work and their organization as a whole, and, in turn, are motivated to help make it an even better place.

We generally see two situations in which organizations create deep engagement.

The first situation is driven by the individual. A chef at a restaurant with a Michelin star lives to cook and can make his dreams become reality. An engineer at Porsche lives for sports cars and can apply her talents to mastering her craft surrounded by likeminded, equally passionate engineers.

The second situation is driven by leadership. This form of deep engagement occurs when individuals know that they are cared about as a person first, and as a vehicle to accomplish work second.

This remains a rare achievement and, as such, has the potential to contribute to competitive advantage. It may also be particularly important in today’s Vuca (volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous) world, in which uncertainty and ambiguity are high, and risk-taking fundamentally important.

Why should individuals have the courage to make mistakes, unless they know they are cared for as individuals by their leadership? Why isn’t deep engagement being adopted?

We believe two principles – missing at most large organizations – facilitate deep engagement and thereby contribute to a company’s competitive advantage.

Principle 1 – People before rules

Treating people as individuals sometimes requires rules to be broken. Most organizations spend far too little time discussing under what conditions rules should, and should not, be broken. And most individuals spend too much time imagining that more rules exist than is strictly true.

When a young Hervé Coyco was working late for Michelin tyre manufacturer one Friday night, his boss’s boss approached him – remembering that Coyco was getting married the following day. “Why are you still working?” the executive asked. Coyco replied that he needed to be sure his team had instructions for the following week while he was on his honeymoon. The manager asked why he was only taking one week for his honeymoon. Coyco explained that he only had accrued one week’s worth of annual leave. The chap ordered Coyco to take two weeks. When Coyco said, “But my boss…” the executive replied, “I will speak to your boss.”

In this example, the big boss breaking the rule about annual leave contributed to Coyco wanting to build a career at Michelin, and fostered his desire to do his absolute best for the company.

There is, however, an essential note that must be made to this story: ‘people before rules’ must be genuine. The message is not for leaders to learn a handy ‘people engagement’ recipe, but for leaders to be aware of the value of empowering individuals to break the rules and creating a culture with clear guidelines as to which rules can – and cannot – be broken.

Now consider a contrasting example. When Roger Hallowell was a research associate at a well-known business school, he was frequently on the telephone conducting interviews. He had been paired with another researcher in an office slightly larger than a coat closet, making interviewing awkward. Hallowell noticed that there was an empty faculty office next door and there were no plans to place anyone in it.

Physical space was an indication of status at this institution; faculty offices were for faculty. Despite knowing this, Hallowell moved only what he was working on at any given moment into the empty office, and kept himself capable of vacating the room within five minutes. Productivity and quality rose and, for a time, everyone was happy. After about a month, however, rumour of the transgression spread and the rules were enforced. The off-limits empty office sent the message that rules were more important than people and their work.

These two examples – one engendering a lifetime of loyalty to an organization, and one demonstrating that a bureaucratic rule was more important than people – illustrate the opportunities of responsible rule-breaking. What can we learn from this? When should you, and when shouldn’t you, break the rules?

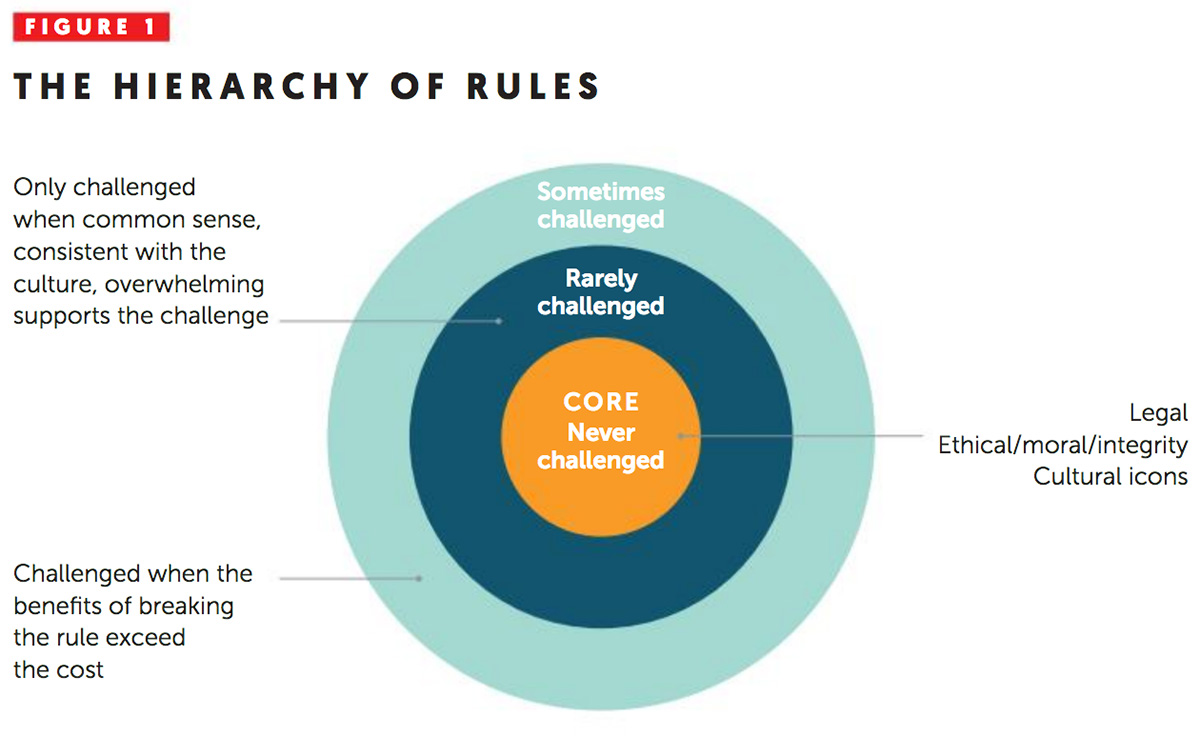

Break the rules when the long-term benefits of breaking them exceed the long-term costs (note that this requires a long-term perspective). Take a look at the hierarchy of rules (see Figure 1): at the core are rules that are never challenged. The most straightforward examples of these involve legality. Slightly less straightforward are those involving ethics, morality and integrity.

More subtle rules that are never broken often relate to cultural icons. For example, for many years at Michelin it was understood that one would never propose a change to decrease costs unless it simultaneously increased quality.

Moving out from the core of Figure 1, we experience a set of rules that are rarely broken unless common sense and the organizational culture overwhelmingly support their being challenged.

Once a flight ‘closes’ at Singapore Airlines, no more tickets can be sold… except that this rule was broken when Coyco was struggling to get the last flight from Singapore to Paris due to a family emergency. Singapore Airlines’ culture is about being customer-centric. If a flight isn’t delayed, the only inconvenience of ‘reopening’ a flight is administrative hassle: a cost well worth incurring when you can help a fellow human-being in a crisis and thereby reinforce the airline’s culture and strategy – not to mention boost revenue.

Moving further out from the core of Figure 1, we see rules that are sometimes challenged. In making a reservation for a rental car, Hallowell’s corporate travel agent cheerfully broke the rule against renting out SUVs when she learned that he would be driving across the plains of South Dakota in February, where the temperature could drop to -40oC, accompanied by a metre of fresh snow.

Laid over the very simple framework we have provided, a leader at any level in an organization may consider breaking rules based on need. But will a person or group abuse the freedom they are being given?

There is no contradiction in having rules and giving people degrees of freedom. This is not a zero-sum game in which increasing one automatically reduces the other, as long as leaders have a clear understanding of when and which rules to break.

At organizations with extraordinary cultures there is an innate understanding of when to break rules. For most organizations, however, the question of when to break rules is opaque at best. We would encourage leadership of all organizations to have an open dialogue about breaking rules.

Only if an organization creates its own version of our Figure 1 can it be sure that some rules will never be broken, but that other rules can be subject to judgment and common sense. Open dialogue is an essential part of ensuring individuals believe that their organization puts people first.

Having some rules about rules will help all leaders intentionally ask the right questions. Emotionally intelligent leaders, supported by a good culture, instinctively know when to break the rules.

Principle 2 – Emotional leadership

A lot has been written on this topic, but its execution remains elusive for many leaders.

Deep engagement requires leaders of an organization to capture individuals’ hearts, just as Coyco’s boss’s boss did. This starts at the top of the organization through behavioural modelling, and then cascades to the entry level.

When done effectively, the organization’s culture reflects the belief that individuals are human beings first, and vehicles to accomplish work second. During Hallowell’s first visit to study Southwest Airlines, he was struck by the enthusiastic way individuals greeted each other at headquarters. What initially appeared to be excessive Texan friendliness turned out to be genuine concern individuals had for one another. Did this come out of nowhere?

Herb Kelleher, then chief executive, applied emotional leadership extraordinarily well, genuinely caring about his people and insisting that those behaviours cascade through the company.

Kelleher stated: “We say, ‘If you’ve got problems at home, we understand that and we want to help you deal with your problems at home, because Southwest is your family too’… We aim to constantly show that we care about our people as individuals number one, not just as part of Southwest Airlines, but in the totality of their lives.”

In a business-to-business context, another chief executive delivers a similar message. C William Pollard, former chief executive of residential and commercial services giant ServiceMaster, wrote: “When I was in… St Petersburg, I met Olga. She had the job of mopping the floor in a large hotel, had been given a T-frame for a mop, a filthy rag, and a bucket of dirty water to do her job. She wasn’t cleaning the floor, she was just moving dirt from one section to another. I knew from our conversation that there was great unlocked potential in Olga. I am sure you could have eaten off the floor in her two-room apartment – but work was something different. No one had taken the time to teach or equip Olga. No one had taken the time to care about her as a person. She was lost in a system that did not care…”

ServiceMaster learned the hard way that getting competitive advantage requires beliefs and behaviours that are echoed throughout an entire organization to create a culture of caring.

Principle 3 – The Goldilocks principle

Deep engagement can occur in any organization, at all levels, when our two principles are applied: (1) putting people before most rules; encouraging discussion about when rules should and should not be broken; and (2) engaging in emotional leadership; capturing the hearts of your people by showing them you care about them as individuals first, and as a vehicle to accomplish work second.

A critically important note: both ‘people before most rules’ and ‘emotional leadership’ can’t be some kind of algorithm. They require true leaders who are empowered and who possess good judgment. Too much rigidity will diminish the moments of truth when deep engagement can be initiated or enhanced. Too much flexibility defeats the purpose and can create long-term problems. What’s needed is ‘Goldilocks Leadership’ – not too hot, not too cold – but just right.

Is developing emotional leadership throughout an organization a difficult goal? Absolutely, otherwise people would have stopped writing about it by now. This is why we think being clear about which rules cannot be broken and which can be flexed, changed or challenged, is so important. As is the development of emotional leadership.

— Hervé Coyco, Roger Hallowell and Randall White are adjunct professors at HEC Paris.

An adapted version of this article appeared on the Dialogue Review website.