Legacy companies urgently need to rethink their operating models – and there’s more to it than just copying the digital disruptors.

There is a widening gap between the external dynamism of markets and the rigidity of many companies’ internal operating models – and it is one of the biggest issues that businesses now face. Outside, the needs of consumers and stakeholders are being quickly transformed by economic, societal and environmental trends that demand more flexibility and adaptability in how companies operate. But inside, most firms are still functioning with operating models based on decades-old management practices driven by bureaucracy and strict control.

Digital native companies, such as Google and Netflix, are exceptions to this general managerial reality. With no legacy structure they have been able to organize themselves in a more agile fashion, fully synced with today’s dynamic context.

The temptation for traditional companies is to copy the operating models of such digital champions. For example, when ING Bank’s executives initiated the firm’s agile transformation, they visited Spotify and were fascinated by the company’s organizational model of tribes and squads. But applying the Spotify model in a large company such as ING proved challenging, with a great deal of unanticipated complexity – such as dealing with layer upon layer of procedures, industry regulations and deep cultural norms.

In our consulting experience, we have seen several legacy companies attempt similar journeys from traditional to agile – with mixed results. The inconvenient truth is that companies with strong legacy models cannot simply adopt the way that Google, Netflix or Spotify have organized themselves in the absence of a legacy model.

The reality is that established companies do have a legacy. Their history cannot be ignored: they must find their own way to modernize their operating models. If copying the digital natives is not a viable option, how should traditional firms reinvent themselves to stay in sync with today’s dynamic context?

The Reinvention Circle

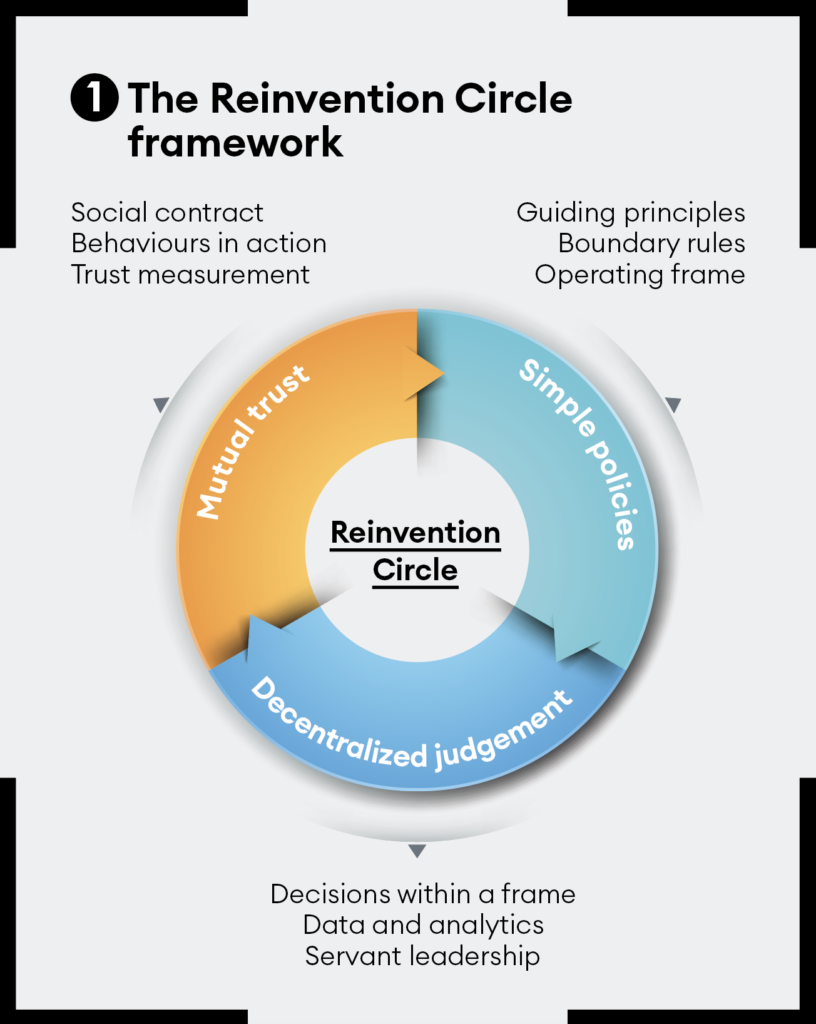

Starting from Donald Sull and Kathleen M Eisenhardt’s pioneering work on ‘Simple Rules for a Complex World’ (Harvard Business Review, September 2012), leveraging Gary Hamel and Michele Zanini’s thinking on debureaucratization (‘The End of Bureaucracy’, HBR, Nov-Dec 2018) and through our own research on judgement and trust, we have designed a closed-loop framework to help large established corporations modernize their legacy model. The framework – labelled the Reinvention Circle – consists of three main elements: Simple Policies, Decentralized Judgement, and Mutual Trust.

The underlying logic is the following. Simplification gives more freedom and empowerment to employees; within these new boundaries and guidelines employees can make quality decisions at their local level. For this to happen, managers must foster the conditions to help their collaborators perform, acting as coaches, providing the right data and tools, and establishing mutual trust. Once mutual trust increases, it becomes easier to further simplify rules.

There are a number of examples of traditional corporations, in sectors ranging from financial services to energy to industrial goods, that are pioneering an approach along the fundamental principles of the Reinvention Circle. Take the case of the global energy company Enel (a company we have worked with as consultants). Enel was founded 60 years ago. It is now undergoing a deep transformation of its legacy model while driving the energy transition, moving towards electrification and a sustainable future for all. The company’s chief people and organization officer, Guido Stratta, has started a reinvention of the firm’s management style and culture, shifting to what he defines as “kind leadership.” It is a move away from a bureaucratic command-and-control model to an empowering, motivating and purposeful one based on mutual trust, creating the environment for people’s passions and talents to bloom. As part of this reinvention, Enel is tackling several components of the operating model, with a particular focus on traditional processes, policies, and procedures in different areas of the firm: from investment approvals and business development, to hiring and onboarding processes, to travel policies and procurement.

In line with the Reinvention Circle, Enel’s first step was to define simple rules: boundary conditions, thresholds, and guiding principles for thousands of Enel employees, enabling them to be freer to make decisions based on their autonomous judgment. For example, the group’s travel policy was made simpler by putting boundaries on a trip’s total cost rather than capping individual items. Seven approval circumstances were eliminated. Employees can now judge for themselves what the best solution is for their business: is a flight necessary, or can a meeting be held remotely, considering the health and environmental trade-offs? The role of managers has shifted from authorizers to context-setters. A similar logic was applied to the hiring process, where shortcuts were made possible with the aim of being more flexible about urgent needs that were otherwise being left unmet.

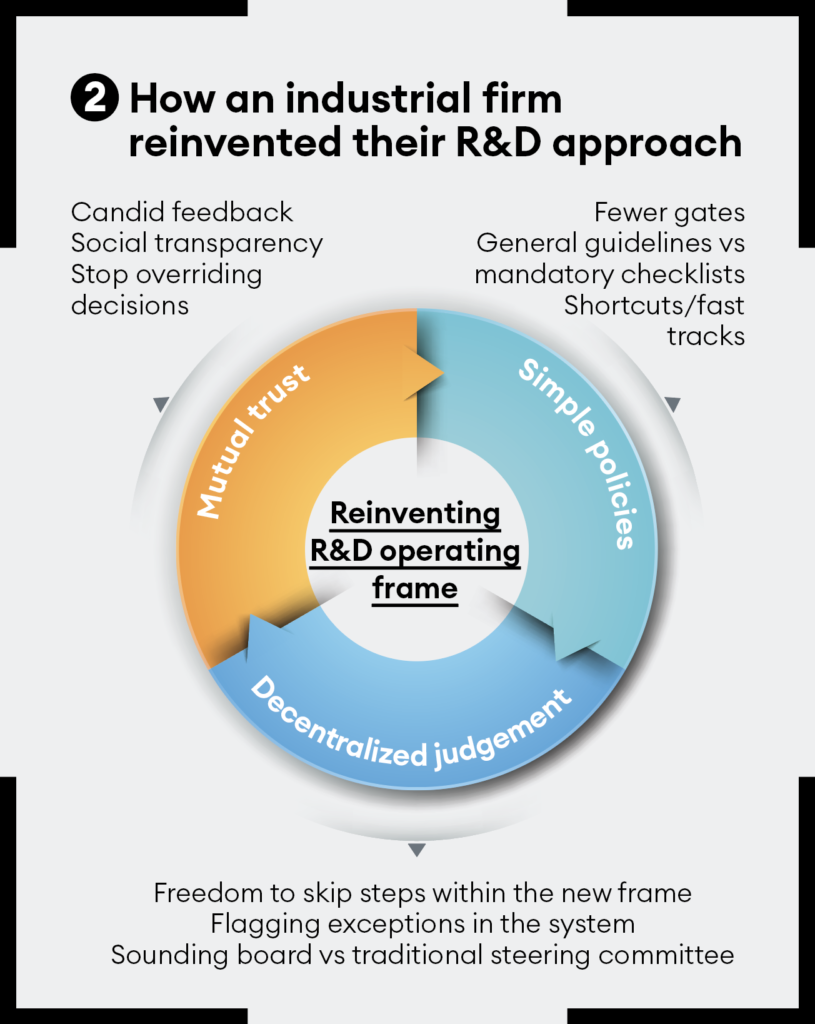

Looking at a different industry, an industrial corporation applied the framework to de-bureaucratize its R&D funnel, known as Stage Gate, aiming to speed up the new product development cycle. Previously, the company’s development process for a new idea involved over 100 steps, perfectly illustrated in a detailed handbook.

To radically change the approach, the firm introduced room for flexibility and judgement, setting out guidelines that allow its people to make decisions about which steps can be skipped in certain situations.

Now, the steps are seen only as a reference source from which employees can choose, determining which tasks are unnecessary and can be eliminated. Executives act more as sounding boards and official steering committees have been reduced in number too, allowing for greater informality.

Decision-making and data literacy

These examples illustrate the importance of having simple policies as a necessary precondition for timely decisions. Judgement and trust are also key. When employees are not bound by a host of prescriptive rules, they need to exercise decentralized judgement. Making decisions at a local level requires that employees have access to information and data – and know how to process it.

It is easier than ever to give employees access to systems and data, but access by itself is not enough if employees do not know how to leverage the system and extract insights from data in order to make good decisions for the business. Therefore, data literacy must become a widespread capability right across organizations. In other words, all employees need to be able to analyse relevant data independently.

One firm working to improve its data literacy is GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), the British multinational pharmaceutical company, which has recently launched a Data Academy to drive up data literacy among its 95,000 employees. The Academy’s programme is organized around three distinct personas for data literacy: ‘experts’ (data and analytics professionals), ‘users’ (the majority of people, who need to use data and tools to get insights for their daily tasks) and internal ‘consumers’ (those such as managers, who traditionally look for business metrics).

Early evidence suggests that these efforts are paying off: 20,000 of GSK’s 100,000 employees have interacted with the Data Academy content since its launch in June 2021.

Decentralized judgement also implies room for exceptions, understanding why the guideline in a particular case might not need to be followed, or should be adapted to the circumstances. (Of course, while exceptions are possible, they need to be flagged in an auditable and transparent way in the system.) Handelsbanken in Sweden and Affinity Bank in the US are pioneering ways to enable autonomous judgement at their local branches.

The new role for leaders

Decentralizing decision-making casts leaders in a new role. They need to create the conditions (tools, data and systems, skills, and so on) to help their collaborators perform. They have to act as a sounding board, providing coaching and removing obstacles, rather than controlling and monitoring the execution of tasks.

Such a shift in leadership style is not easy to achieve. Building and sustaining trust can be difficult for leaders, as they often have to unlearn many of the beliefs and practices associated with traditional management. Consider a leader who frequently overrides the decisions of subordinates without providing appropriate explanations. This behaviour is unfit for trust-based processes as it undermines the ability of employees to make autonomous decisions within clear guidelines. It demotivates employees, leaving them disengaged and frustrated, and sapping their willingness to contribute. To avoid this trap, leaders need to identify a list of concrete and actionable behaviours that they commit to start or stop doing. At Enel, for instance, we designed a Trust Behavioural Index measuring the level of trust of each manager on several categories, such as vulnerability, credibility, and empathy. Initially tested on HR executives who were role-modelling behavioural change, the Index helped to highlight gaps and opportunities to improve trust levels.

Three phases of change

The operating model of a large established company consists of numerous processes, procedures and management practices. Clearly, change does not happen overnight. According to Enel’s Guido Stratta, “the shift requires that you win the hearts and the minds of both employees and leaders along a transformational journey”. There’s no one-size-fits-all recipe that one can engineer from the top down. It’s a learning experiment in which each company needs to find and tailor its own model. It is advisable to start small with some experiments. In terms of approach, we suggest three phases:

Test phase Select a few processes to start with; engage with real users; identify critical decision points in the current process; brainstorm on creative application of a set of new models for decision-making and control; draft a ‘version 1.0’ of the new process. In parallel, make sure leaders commit to trust-based behaviours, and provide employees with the right context and supporting tools.

Learn phase Run a test on a sub-area of the firm (a unit or a country); measure the results with clear KPIs (including behavioural components); collect the learnings into a toolkit with company specific examples that can be shared in other areas as internal reference cases.

Scale up Disseminate the approach to other processes and procedures, set up methodological training, share experiences and build a community of practice.

The reinvention of legacy models is desperately needed. Three ingredients are key: simple policies, decentralized judgement, and mutual trust. All three are necessary for an effective recipe: simple policies free up autonomy, judgement is needed for freedom and autonomy to be used in the best interest of the company, and trust ensures the support of leaders for their teams.

Pioneers in traditional industries demonstrate that established firms do not need to copy Netflix or Spotify. They should instead find their own way, evolving their legacy model to a more modern way of functioning.

Paolo Cervini is vice president and Gabriele Rosani is principal at The Management Lab by Capgemini Invent.