Embrace this moment of change.

In March 2020 most developed economies began a global experiment in homeworking, at an unprecedented scale and at lightning speed. Within just a few days, millions of workers found themselves compelled to work at home, with an expectation that they would maintain their productivity without breaking step. By the end of April, the proportion of employees working at home had soared from 12% to about 50% in the USA and 44% in the UK, representing the most extensive and rapid shift in working patterns in peacetime.

As the post-lockdown return to work has got under way, senior leaders have been trying to make sense of this shift, and to ensure that they get back to what passes as ‘normal’ as quickly and seamlessly as possible.

For some, the plan is to snap back to how things were before, as soon as possible – but others have tuned in to the fact that the pandemic has created a rare opportunity to rethink how their organizations work in a more daring and disruptive way than they ever imagined possible. For these leaders, the ability to experiment with remote working, virtual teams, novel approaches to organization and job design, and innovations in flexible working, has represented a great opportunity to consider disruptive changes to the way they do business.

Remote working – thriving or surviving?

The first step in considering whether lockdown has taught us any enduring lessons is to check how well employees coped with the experience, to build on the positives and mitigate the negatives. In the UK, our survey of 900 people working at home was launched within days of the lockdown. We measured their engagement and motivation, their health, and the impact of homeworking on their work-life balance. We found that:

- More than four in ten shared a space at home with another working adult. A third lived with dependent children and 16% provided care for another adult or elderly relative

- Over 70% of respondents were working at home directly as a result of the lockdown, so had make a rapid transition to homeworking

- Almost half (44%) reported losing sleep due to worry and 42% reported more fatigue than usual; 36% said their work pressure in lockdown was “too much” and 43% did not have enough time to get their work done

- One in five said their alcohol consumption had increased and 60% worried they exercised too little.

Those respondents with the highest mental wellbeing scores were those who were older, had autonomy and control over their work, felt supported and motivated to work from home, had more frequent contact with their boss, and had fewer physical health problems.

We found that, as lockdown went on, mental wellbeing and a general sense of ‘coping’ improved somewhat, and an increasing number of employees claimed that they would find it hard to go back to working and commuting as they had in pre-lockdown days. This offers hope to those leaders who have ambitions to permanently alter the pattern and location of work as they manage the return to work of thousands of employees. This could be a very liberating change, turning a threat into an opportunity.

Does work need to be a “place?”

Some recent research in both the UK and the USA has identified a clear gap between those whose jobs can be performed at home and those for whom it is impossible. Unsurprisingly, the former are almost exclusively professional, R&D, public administration and “white-collar” jobs, and the latter are those in retail, hospitality, healthcare and so on.

However, there is a range of other roles where the choices may not be so clear-cut. Here, innovative approaches to flexible working, self-rostering, rotation between ‘A’ and ‘B’ teams of employees doing similar work, or work in intermediate ‘hub’ locations, can reduce the need for long commutes or slavish compliance with the tradition of nine-to-five office occupancy.

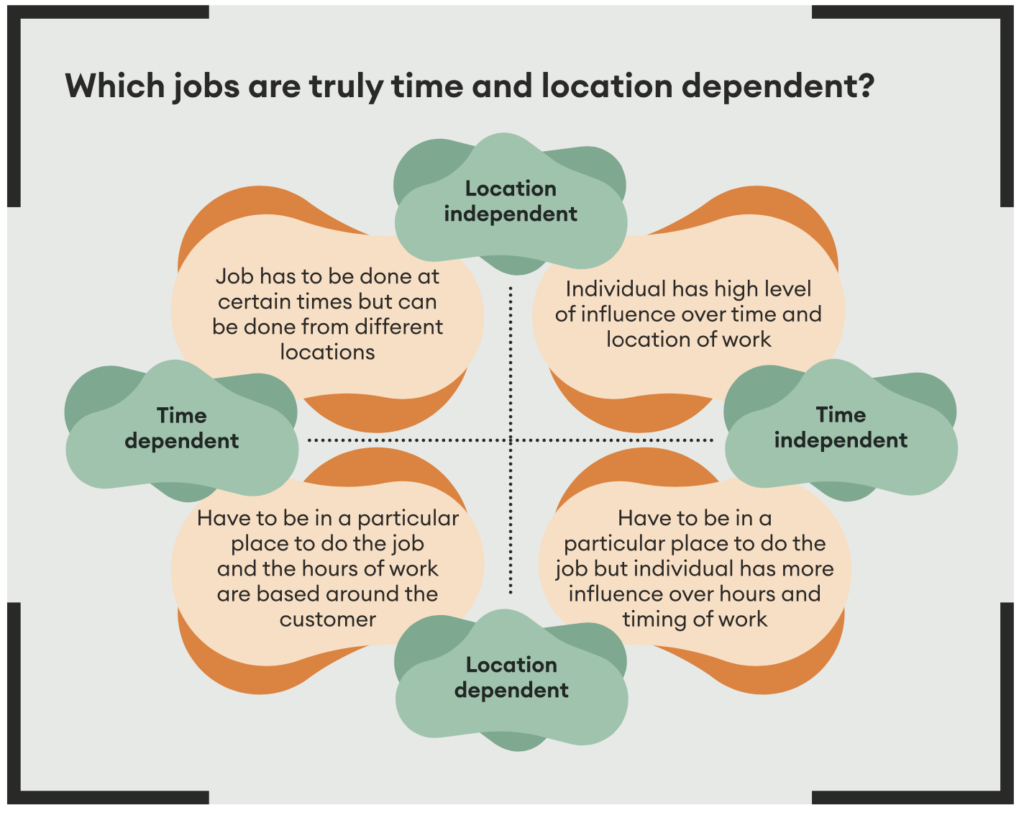

In the diagram above, I share a simple framework which I have been using to support several organizations to think through alternative approaches to managing the return to work after lockdown. It simply challenges businesses to ask which jobs can genuinely only be performed at a fixed location and at a fixed time, or whether some are rather more independent of time and location than has previously been conceded.

Of course, the ‘voice’ of employees matters here, as consent for changes to working time and location is important. But my experience is that leaders who show some imagination and flexibility about how their people work get repaid many times over with enhanced loyalty, flexibility, collaboration, productivity and retention.

No going back?

Leaders who have always harbored an ambition to subvert the status quo and to try new working arrangements have been given a helping hand by Covid-19. A substantial proportion of employees have tasted the upsides of more flexibility, autonomy and trust while working remotely: if they want to hang on to these advantages once the crisis subsides, then the appetite for novelty will grow. Unlocking this readiness for change may release the potential for sustained improvements in innovation and team working, and may even reveal new sources of competitive advantage.

– Stephen Bevan is head of HR research development at the Institute for Employment Studies.