The art of doing well by doing good.

Many people operating in today’s complex and uncertain environment have already figured out that their traditional ways of doing business no longer have a place in today’s marketplace. Between the financial crash and corporate scandals to environmental crises like climate change and an overabundance of plastic waste in our planet’s oceans, business thinkers have been forced to contemplate new approaches to their industries. Until not long ago, many assumed that business interests were directly in conflict with social and environmental concerns. Yet recent research findings challenge this assumption. As it turns out, you can secure superior financial returns through highly engaged staff who display social and environmental responsibility.

I have had the privilege of interviewing 58 business leaders at the forefront of this change for a forthcoming book, Humane Capital. It validates, and builds on, the research I completed for an earlier work, The Management Shift (Dialogue, Q1 2016, page 36), which identified five levels of engagement and performance of staff, from Level 1 – actively disengaged, to Level 5 – passionately committed. It also explained how to align engagement initiatives with strategy and processes to harness this commitment to serving customers.

The new book features 35 case studies from the corporate sector, public sector, non-profit and small- to medium-sized enterprises; 50 strategies for making the shift for each sector, some 200 in total; eight pillars for creating a humane, high-performing organization, based on a total of 272,000 words of research transcript.

The links between being a great employer and securing better business results may appear to apply mostly to young dynamic companies in the creative sector. For example, the UK digital marketing agency Propellernet, one of the case studies in Humane Capital, has a waiting list for individuals wanting to work there. Founder-entrepreneur Jack Hubbard offers benefits that include making an employee’s dream come true. Every month, as the company achieves the revenue target, a lottery is held to send a staff member on their chosen prize, such as a safari or a trip to the World Cup. Since making the shift, engagement and financial returns have soared, and the small company registers £1 million net profit on turnover of just £4 million.

The bigger challenge is: can the principles apply in more grown-up companies, with tens of thousands of staff, operating in regulated industries?

This is where the results from the research described in Humane Capital get really interesting. The lessons are equally applicable, and some major companies are making the shift. For the past eight years, the global consumer goods giant Unilever has reoriented itself around social and environmental goals, rather than quarterly earnings targets. Its mission is to enhance the welfare of its customers, double its turnover, while reducing its environmental footprint. Between 2010 and 2017 its employee engagement scores went from the mid-50s to the 80s. It became the third most sought-after brand to work for, according to LinkedIn, after Google and Apple. Far from compromising commercial performance, returns have been impressive: the share price has more than trebled, from £11-12 to £38-40 by mid-2018. In a similar way, the pharmaceutical giant Roche is switching its mission from purely financial targets to ones based on wellbeing and quality of life of the patients that they ultimately serve.

In my work with large companies, I find that high trust and engagement helps compliance with regulations such as health and safety and data protection, so there is no trade-off. And the high-engagement approach is equally applicable in the government and nonprofit sectors, as many case studies in Humane Capital illustrate.

There are multiple benefits to making such a shift. As my interviewee Karin Tenelius, chief executive at Tuff Leadership Training, puts it: “Efficiency goes up, profitability goes up, there is a high quality of service and happier customers. Innovation happens.” Some interviewees reported returns on investment that run into the millions, while stressing that the benefits extend beyond the financial, using terms like ‘priceless’ and ‘magic’. Some credit the switch to a high-engagement, high-performance workplace with the very survival of the business.

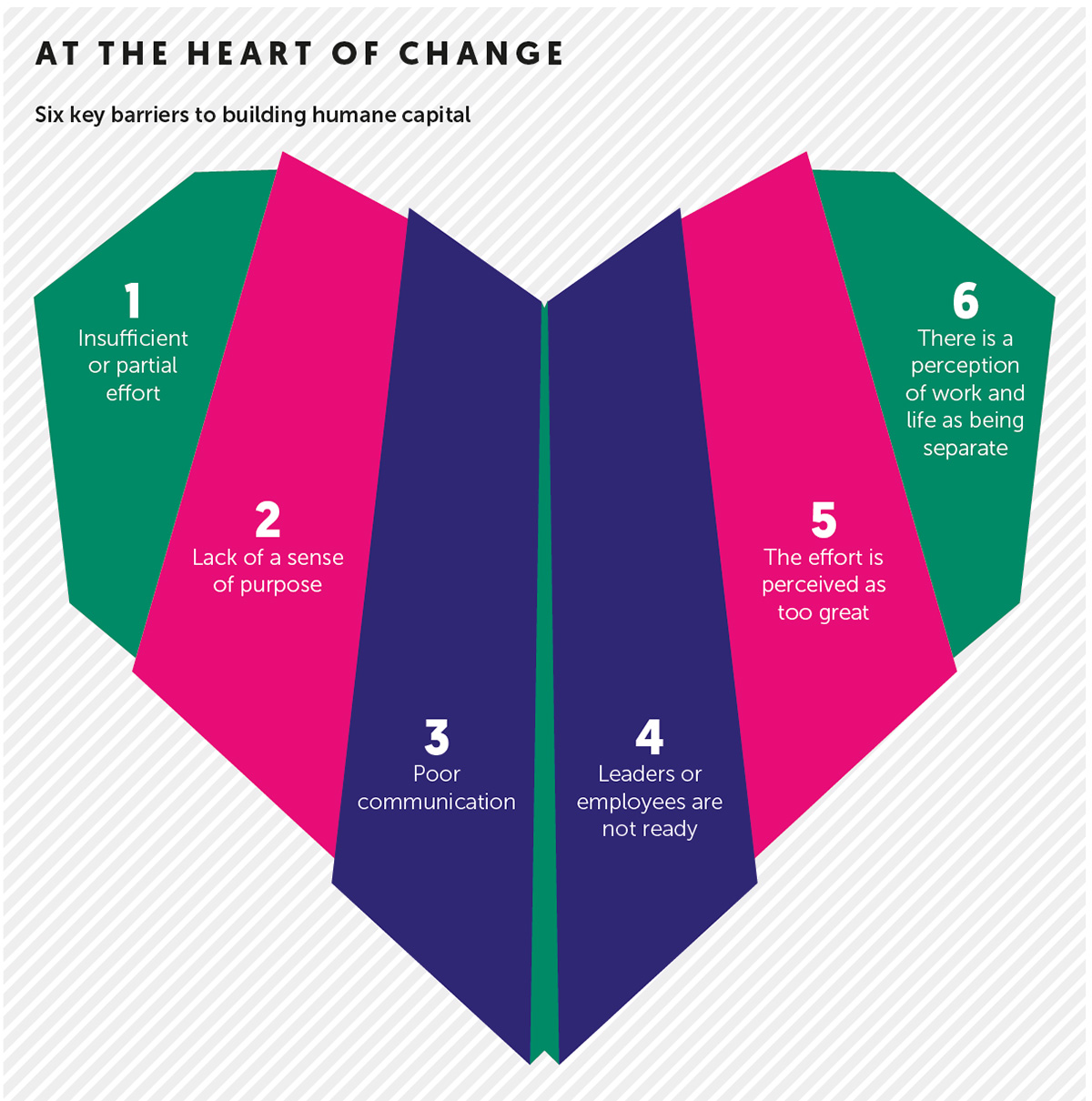

So why is such an approach still comparatively rare? The barriers fall into two main categories: at a practical level, and to do with mindset.

Practical problems can occur when an attempt is made, but the effort is halfhearted, so the initiative loses credibility. Or there can be a lack of an overriding sense of purpose, for example where the company has grown by acquisition. Leaders sometimes devote insufficient time to communication. Or the employees may have had a negative experience of change programmes, and are mistrustful of a new initiative.

Yet my research persuades me that the biggest barrier is in the mindset of those leading the change. Despite all the evidence, many people refuse to believe it is possible or necessary. In an interview for the book, Steve Denning, former programme director for the World Bank, said: “If you don’t have that [empowering] mindset, it doesn’t matter what methodologies or what practices or what systems you put in place, everything goes astray.”

The shift isn’t just a set of best practice tactics, it’s a radically different philosophy of what an organization is, what sustains it, and how it can be led and managed.

In the successful cases, the people leading this business transformation ‘get it’, deep down. They understand the enterprise as a network of intelligent people, not a set of inanimate departments or resources. They know that they can’t know everything as a small elite, and so they have to harness the collective inventiveness of all. They know that they are a part of society and the environment that ultimately sustains the business.

For all the threats and disruptions in the modern world, there is cause for an optimistic take, in that the more participative, enlightened ways of work do bring lasting competitive benefits, as the case studies in Humane Capital show. So what happens if we don’t shift?

Some change is happening through market pressure. A top-down approach to management results in organizations that are slow to adapt to rapidly changing technology and business models, the digital transformation now known as the fourth industrial revolution. Mark Esposito, professor of business and economics at Harvard University, said that Humane Capital “pushes an open door in the direction of how the fourth industrial revolution envisions the role of organizations in the 21st century”.

Paul Polman, chief executive of Unilever, said in an interview for the book that the financial crisis of 2007/08 raised profound questions. “I think a lot of people started to realize on a micro level not only that companies needed more of a purpose, but that we needed to also transform our economic system … The overconsumption, the environmental stress and climate change being among them … If you don’t tackle it [the environmental crisis], the cost will be higher. So if we don’t address these issues, we will challenge our own existence, ultimately.”

Humane Capital is a practical handbook, containing proven models that align beliefs, strategies and resources, summarized in eight pillars of the humanized organization. It is a challenge, but one with considerable rewards. Ultimately, it is less problematic than ducking the issues the business world faces.

— Professor Vlatka Hlupic is chief executive of The Management Shift Consulting, professor of business and management at Westminster Business School and visiting professor at Birkbeck, University of London

— Humane Capital by Professor Vlatka Hlupic, with a foreword by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, will be published by Bloomsbury in October 2018

The accompanying Humane Capital board game will also be available from October, helping organisations put lessons into practice

— Illustration by Cajsa Holgersson

An adapted version of this article appeared on the Dialogue Review website.