In many respects, the complicated tangle of strategic agility can be boiled down to three basic factors: the market, the organization, and the human.

In General Electric’s 2000 annual report, CEO Jack Welch described in no uncertain terms the potential conditions that would lead to GE’s fall: “We’ve long believed that when the rate of change on the inside becomes slower than the rate of change outside, the end is in sight.” This comment turned out to be eerily prescient. Today, GE – once one of the most valuable and greatly admired companies in the world – is a shell of its former self. Since 2000, its market value has declined almost $500 billion. But GE is not alone: just over half of the Fortune 500 have disappeared since then.

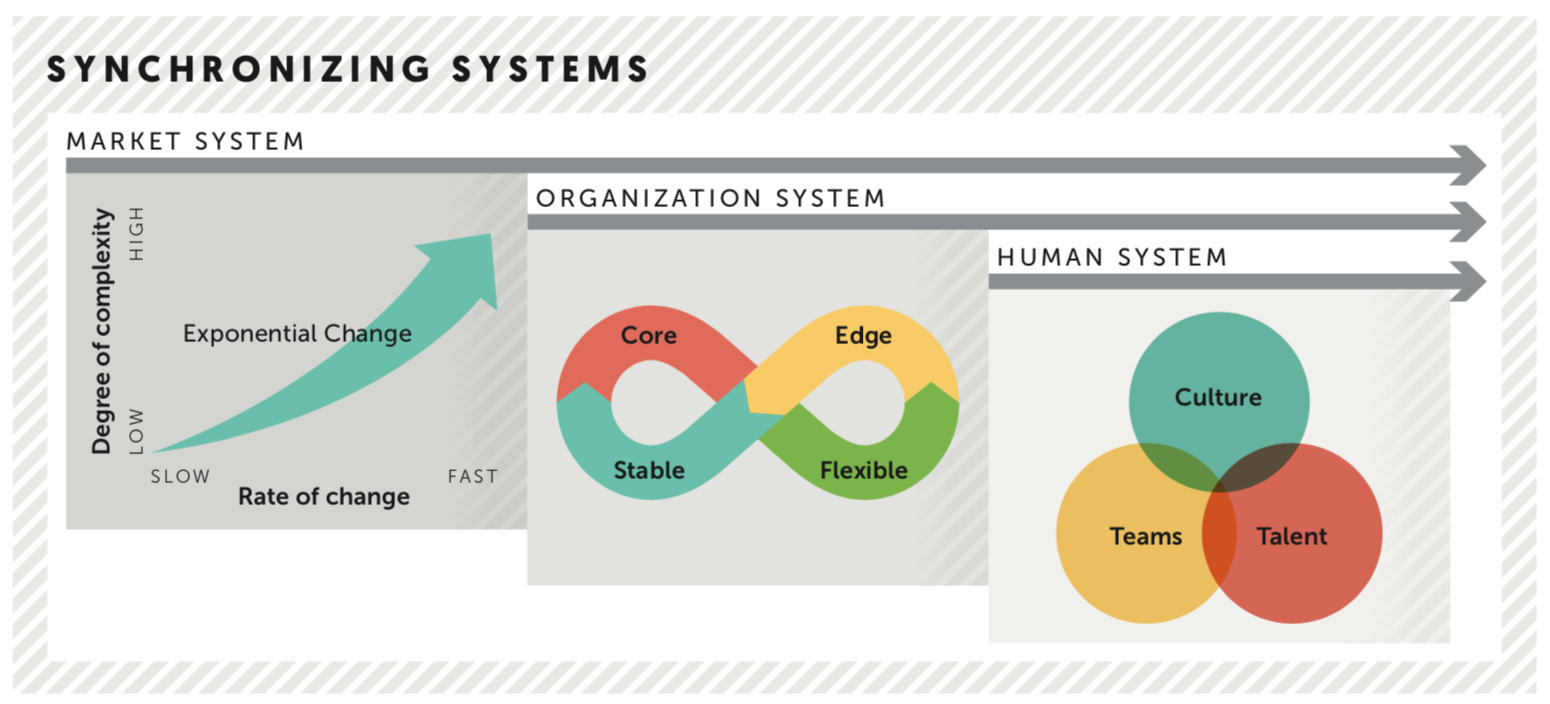

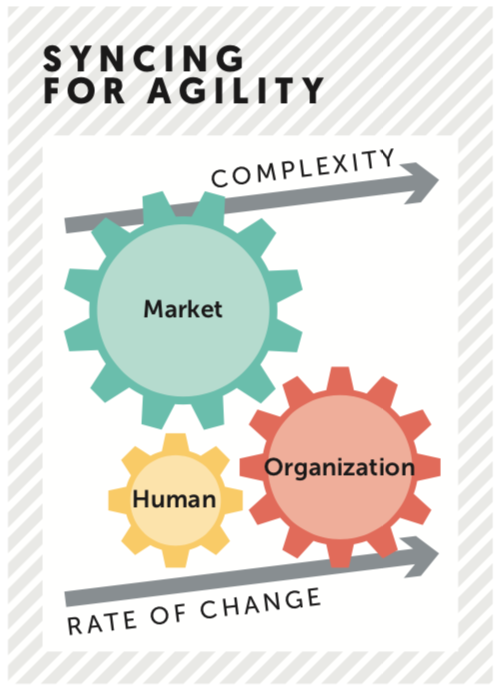

To understand the agility imperative, leaders must understand the ‘spin rate’, or speed at which the markets, organizations and their people change and evolve. Challenges occur when these systems move at different speeds. In the case of GE, the market is spinning faster than the company can keep up.

Linear to exponential change

If the keyword for the 20th century was ‘speed’, the keyword for the 21st century is ‘agility’, as organizations struggle to learn how to play an ever-evolving game of business on an increasingly accelerating and shifting playing field where speed alone is insufficient to ensure success.

Change is not new: we’ve been dealing with it for as long as commerce has existed. But the velocity and scope of change today is very different. We can look to mathematics for insight. In calculus, the first derivative of distance is velocity and the second is acceleration. Today’s market environment is experiencing what mathematicians call the third derivative: the rate of the increase in acceleration, or ‘jerk’.

According to Visual Capitalist, television ownership took 22 years to reach 50 million customers. Facebook took a mere three to reach the same milestone. Pokémon Go reached 50 million people in 19 days. If the pace of change was recorded by a metronome, its needle would have broken.

The flow of goods, information and capital flow around the world is rapidly accelerating. This, coupled with the explosion of new technologies disrupting every industry requires us to move from managing a linear notion of change to an exponential one. Managing at this accelerated speed of business is the first challenge organizations and their leaders must address.

Complicated to complex

As the former chief executive of Google, Eric Schmidt, notes: “Every two days we create as much information as we had available to us in 2003. More to scan, know, learn. But the real challenge is getting to insights that matter more efficiently.”

A simple way to think about complexity in this context is that it increases exponentially as you increase the number of variables and connections between the variables in a system.

Less than two decades after the introduction of the Mosaic browser, a projected 6.4 billion digitally connected things are in use worldwide, with millions more connecting daily. As people and things become even more interconnected, the complexity will continue to increase at mind-boggling rates.

New strategic paradigm

Plotting strategy is no longer a game of chess. In a linear world, strategy was more straightforward. Companies could predict what might happen in the environment, mobilize resources and respond to the market.

If the 20th-century definition of competitive advantage was defined by Michael Porter, the 21st-century definition is now influenced by Rita McGrath. In her book The End of Competitive Advantage, McGrath argues that competitive advantage is transient. It is both ironic and prophetic that previous strategy guru Michael Porter’s consulting firm Monitor went bankrupt.

Today, maintaining competitive advantage is like riding a wave. The strategic question is no longer whether you can create sustainable advantage by riding a single-value wave, but how long you can catch and ride a wave before it crashes while positioning yourself to catch the next value wave without being crushed by it.

Strategic bets are still important. But in an uncertain environment, the odds of winning go up by making more smaller bets, more frequently. Organizations must view these bets as learning options and turn them into experiments conducted at speed where people can learn fast and adapt. In Google’s office they have a sign on the wall that reads “Fail Well”. It is not just failing fast, but learning and adapting from each failure. Google’s first foray into mobile phones did not end well financially with its acquisition of Motorola. But the experience was invaluable in its next iteration launching the successful Pixel smartphone.

The agility architecture

In simple terms, agility means having a quick, resourceful and adaptive character. Building an agile organization starts with understanding and managing the interactions across three interdependent and evolving systems:

- The market

- The organization

- The human

Since 2000, GE has faced a market moving much faster than the company or its people, and its next chief executive Jeff Immelt failed to keep GE moving at the same rate. Today, Elon Musk has a different challenge with Tesla. He is future-forward and changing the market. But his companies and people cannot execute as they lack stability for the speed at which he wants them to move.

Hospital systems today face two challenges. The market is moving at a much faster rate than the hospitals. But even the more advanced hospitals are changing faster than the medical professionals they employ can spin.

Companies find themselves in different places and may have different problems within a single enterprise. The trick to creating more agility within an organization is for leaders to synchronize within and across these three systems. This is how we think of the agility architecture, and leaders as its architects. Great architects create structures that fit with the environment, function well and are safe and sustainable. In the same way leaders have to synchronize three systems: the market, the organization and the human.

Market

Market

This digitally intermediated age has given rise to much better informed and connected customers, continually shifting and elevating their expectations. Technology is making the seemingly impossible possible with more choices than ever before. Scale and efficiency as the central driver of value, give way to small batches and customization. And, as it does, organizations need to be intensely customer-focused and rethink how they can create value for their customers across the entire experience, reimagining their partners to deliver.

This speed and endless sense of possibility means that the opportunity for organizations to secure positions of competitive advantage for sustained periods becomes untenable. Warren Buffet and others referred to the moat theory of advantage. The key question is: what is a company’s ability to withstand attacks on its markets and customers? Does it have a defensible position?

But the question today has changed. What if nobody wants to invade your castle? Such was the case faced by Nokia when Apple and Google changed the mobile phone market forever with iOS and Android. It is now the challenge that Apple faces as the touch interface company is being challenged by the voice interfaces of tomorrow.

In the past, leaders would analyse the markets with a degree of predictability and then create capabilities to deliver and capture the value. A pharma company such as Merck could predict with relative certainty the sales of a drug under patent protection. Today, with multiple competing drugs and biosimilar competition, as well as the rise of the prescription benefit manager and the formulary of covered drugs, forecasts are anything but certain. Large batch process manufacturing to drive economies of scale no longer works.

AG Lafley, the former chief executive of Proctor & Gamble, thought of himself as the chief external officer. “I have a dozen executives who run multibillion-dollar global businesses, and I am unlikely to help them improve their performance,” he once said. “My job is to understand what is happening outside of this company and to make judgments as to when we should move to make changes inside to respond to external realities.”

According to Dave Snowden’s Cynefin framework, when faced with a normal or complicated environment, leaders must first sense, analyse, categorize and then respond. But when the world moves to complex and chaotic environments, the script flips. Companies must first probe or act, then analyse and adjust. Today, organizations cannot predict the rhythm and pattern of value waves with more analysis. Rather, leaders must get their organizations more comfortable looking out at an uncertain horizon and learning how to sense and act in real time.

To adapt, companies must be much more externally focused, scanning and monitoring, and much closer to customers working backwards to meet their needs. Today leaders must work in what Russell Ackoff calls a constant state of design, which employs a future-back customer-centric frame on market decisions as well as flexible organization models.

Organization

The challenge of architecting the organizational system involves managing two paradoxes. An agile company must simultaneously operate at the core (business of today) and the edge (business of tomorrow). It must also be simultaneously stable and flexible. These two paradoxes operate in an infinite loop.

The consulting firm Bain says that your core (Engine 1) will eventually erode. They suggest leaders spend 30% of their time at the edge (Engine 2) – the businesses of tomorrow. As McGrath points out, the core business of today will deteriorate and be replaced by the edge business of tomorrow. Many organizations struggle with the balance between the two. Today GE has a deteriorating core, but no longer works effectively at the edge to win the markets of tomorrow. Tesla is an edge business that is struggling to make its model become a scalable core.

When Toyota engineers discuss the vaunted Toyota Production system to plant managers, they preach stability. Only through stable process can they achieve the customizations at high levels of quality from their manufacturing lines. Flexibility without stability leads to chaos. This is the hard lesson learned by Tesla as it struggles to scale from craft production to mass production.

In addition, edge business must stabilize to become future cores. It is great to be a start-up, but companies must work to replicate processes to scale. Many smaller businesses fail because they can do work for a few clients, but not thousands.

We believe leaders are essentially compelled to run two distinct businesses which must interact. Leaders must continuously seek opportunities for growth at the edge, while simultaneously ensuring they are not squandering value within the core. The challenge of knowing when to power up which engine, and for how long, becomes critical to the sustainability of the enterprise.

In this new exponential era, the ‘S-curve’ theory of a lifecycle of a product or business doesn’t hold any more. The disruptions come faster and from non-traditional competition. To navigate this challenge, leaders must recognize when the core (business) is threatened due to a market shift or competitive threat, and inject the flexibility required to position the organization towards the edge. Similarly, leaders must recognize when to impose the stability required to migrate the organization back towards an evolving core once a significant opportunity for growth has been identified at the edge. Leaders need to continually architect the right structures, processes, and work flows to ensure this new type of agility.

Human

We’re experiencing the challenges of stretching existing constructs of organization and leadership well beyond the machine world for which they were designed. Command and control systems are no longer efficient. As companies reorganize workflow and teams to speed up decision-making and organize around customer-driven process, we see organization charts morph from hierarchies to network maps. And as Heather McGowan suggests, leadership models have shifted from“I-shaped”- leading and advancing through their technical skills, to “T-shaped”- combining technical depth with cross-functional knowledge and relationships, to “X-shaped” with multidisciplinary skills and networks.

Our ability to absorb these changes and transform our organizations is directly tied to the rate at which leaders can effect changes in our talent, teams and culture. Two factors become critical to adapting in this exponential era: increasing the readiness and pace of decision-making and improving the quality of the decisions; and the ability to experiment, learn and adapt as part of the process.

As the problems get harder and cut across more boundaries, our instinct is to slow down, gather more information and check-in with more stakeholders to de-risk decisions. But today, when speed counts, slowing down decisions is riskier than moving quicker and adapting.

Increasingly, leaders must be comfortable with what General Colin Powell calls the 40/70 rule. You need 40% of the information to make a decision. Without some data, you are purely guessing. But you must be able to act at 70% rather than waiting for 90%. The extra time it takes to achieve that 20% greater level of certainty is increasingly putting the organization at a slower spin rate than the market.

The second part of the problem is shifting where decisions get made. According to General Stanley McChrystal’s book Team of Teams, two elements are critical to pushing decision making downward: context and transparency. Leaders must provide the context for others to make good decisions rather than set up a system where they make all the decisions. In this environment, others should be able to make the same decisions consistently over 90% of the time. This, coupled with the decision-maker having access to the same information as the leader, the transparency, is critical.

Leaders as architects

Systems, particularly the organization and human systems, are slow and sometimes resistant to change. Yes, they will evolve, but we no longer have the luxury of time. Leaders can be the greatest leverage point, but only if they know how and where to intervene to better sync the market, organization and human systems.

As the spin rate increases and organizations look more like biological structures rather than mechanical ones, leaders need new frames, tools and orientations to become modern-day ‘architects’- designing more agility into their businesses.

Getting leaders ready to be agility architects may be the most important step in securing the survival and success of your organization. The implication for leadership development is profound, as building agility architects, not mere survivors, is a different task.

— Professor Joe Perfetti is an expert in corporate finance and strategy; Tony O’Driscoll is professor at Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business; Michael Canning is global managing director of innovation and new commercial models at Duke CE; Scott Koerwer is an entrepreneur in higher education and business. Joe Perfetti and Scott Koerwer are faculty in Duke CE’s online course on Building Strategic Agility. An adapted version of this article appeared on the Dialogue Review website.