There’s tomes of scholarship that tell us how to deliver more useful employee feedback and performance reviews.

Giving fair feedback is one of the hardest tasks for managers at all sorts of organizations, but it’s also the most important. There’s a huge amount of evidence, academic research, and anecdotal advice about how to make giving feedback a less painful process for both managers and employees. Despite this, 90% of managers, employees, and HR professionals alike are unsatisfied with their organization’s performance review practices. As a result, it is hardly shocking that many organizations are reevaluating how they approach employee feedback.

Yet having analysed the available academic and practitioner literature, we urge HR practitioners to consider the scientific and empirical evidence about feedback before implementing changes to their performance-management practices, because the discussion on the contribution of performance-management processes to the provision of feedback has become tainted by prejudices.

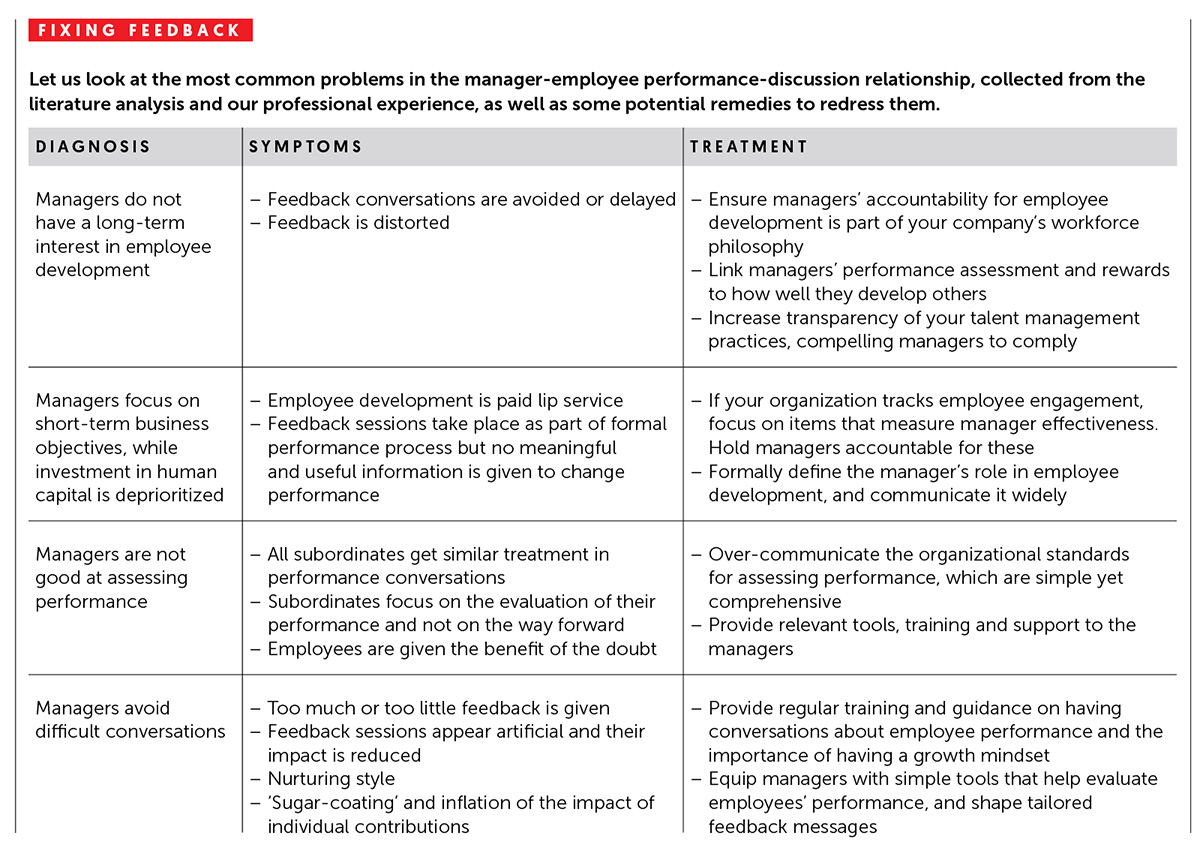

Managers are not entirely to blame, but they are without doubt complicit. Just look at the many reasons managers give for rejecting performance feedback.

- Few managers truly believe that feedback is important for the productivity of their business. They may accept that feedback is useful in the development of individual and organizational capabilities in the long-term, but their focus is on immediate business results

- Political and relationship obstacles get in the way. Managers often withhold feedback, or distort it to be unjustly positive or negative – appraisals get inflated or deflated. Misleading employees about their performance is commonplace

- Managers may be eager to develop their team members, but do not know how. They lack a focused, disciplined means of collecting evidence, and choosing the right words and ways to deliver the message

- Everybody has a point of view and their own theories of how performance at work should be measured and managed. Hence, managers may ditch evidence-based guidance in favour of homegrown fantasies about performance and development

All these factors can be mitigated (see table p43). A feedback culture, where individuals continuously receive, solicit and use formal and informal feedback to improve their job performance, is possible, given three conditions:

- Feedback is of high quality

- Its importance is emphasized in the organization

- There is sufficient support for using feedback

Companies tend to rethink their performance-management systems because they are failing to deliver the one thing they are supposed to be doing – increasing individual and organizational performance.

Research shows that performance appraisal without regular feedback is not sufficient – appraisals must be supported by feedback, otherwise their effectiveness is considerably lower. Simply changing the performance management system, abandoning performance rankings and ratings, or moving from an annual appraisal frequency won’t solve the fundamental issue. All such so-called ‘solutions’ are not worthy of the name – they are effectively throwing the baby out with the bathwater. In a 2016 McKinsey Quarterly article, authors Ewenstein, Hancock and Komm noted that systems designed by HR today do not support leaders in providing useful and timely feedback to their employees.

Getting HR back on the right performance review track

Performance-management systems are often criticized for not increasing performance. Blaming the system, many are abandoning more structured, traditional processes in favour of less structured approaches. But performance depends on fair, focused – and frequent – feedback.

The role of HR departments is to ensure leaders deliver such well-structured feedback by designing solutions that ‘manage’ the complexity, not simply remove it because we don’t like it or can’t solve it. Of the top few dozens of companies listed in Glassdoor’s ‘Best Place to Work in 2017’ award, hardly any have abandoned ratings systems. Yet the most commonly mentioned plus points of working at such places include ‘steep learning curve’ and ‘professional development’ – implying that employees find the existing systems helpful. That said, the actual system is the easy piece to change, while the more difficult and important component is developing the right culture and manager behaviours.

When managers have the right beliefs about feedback, their job becomes so much easier. The truth is that we change and update our beliefs about how this world works all the time. A danger of that is that we are also more likely to be influenced by the ‘bright, shiny objects’ or ‘trends du jour’ – psychologists call these ‘salience’ and ‘recency’ effects. HR must guard organizations and their leaders from such cognitive biases and work hard on building beliefs based on proven scientific evidence.

Traditional cognitive psychology tells us that ‘belief updating’ has a sequential nature. We receive information piece by piece, then we form impressions that grow and change over time, and if we sufficiently repeat the same process with similar information, it becomes a belief. In her latest book Act Like a Leader, Think Like a Leader,

NEW APPROACHES TO PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT

The field of performance management has been in turmoil lately. Consultants get rich. Employees get confused. Leaders get frustrated. Why? Following a small number of high-profile companies abandoning traditional performance management (including Adobe, GE and Accenture), HR executives have positively run to catch this trend to show that they, too, can be on the cusp of the wave. We have seen many examples of similarly attractive propositions – emotional intelligence, authentic leadership, Millennials – but emerging evidence proves that those approaches are either not scientifically robust, or utopian, given the realities of the organizational life.What causes people to latch on to soundbites, or half-truths, or even conveniently distorted facts? Why does a phrase such as ‘employees don’t like ratings’ become a call to redesign approaches to performance management without considering the science?

We aren’t necessarily arguing for ratings – an expert panel debate at the 2015 Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology conference showed that there are as many advantages of doing away with performance ratings as there are drawbacks. But we are arguing for a pause before jumping into a hasty performance-management redesign.

Herminia Ibarra reverses the long-held opinion that we need to think and believe certain things before we behave in ways that are consistent with those beliefs. She brings to the fore the idea of ‘outsight’: behaving like a leader first will lead you to start thinking like one. This brings us to an updated formula that explains how people come to hold certain beliefs: “I know” – “I say” – “I do” – “I believe”. Using it, we develop the messaging for building feedback culture in the organizations:

“I know”

HR must start by equipping organizations with the facts about performance feedback.

“I say”

HR must design smart talent processes that provide practical support to leaders to craft quality feedback and require them to share it.

“I do”

HR must make the process easy and repeatable. Having made it easy, there must be ‘teeth’ in the process – consequences for not doing it.

“I believe”

This is hard work. There is great pressure to satisfy myriad stakeholders who have a vested interest in short-term performance and current relationships. Yet organizations benefit from staying on message, and not abandoning processes in response to short-term trends or fads. With consistency, come results. With results, comes confidence.

Human performance is complex. There is, however, no shortage of scientific evidence on what increases performance. Feedback is one element. It lends itself perfectly to a structured approach, which connects feedback to strategy, to considerations of what and how, to context, and to a learning outcome.

Good feedback is a crucial element in individual and organizational performance. It is time to support it with improvements; not shortcuts.

— Sergey Gorbatov is director general manager of development at AbbVie in Madrid, Spain and adjunct professor at IE Business School. Angela Lane is vice president of talent and development at AbbVie in Chicago, Illinois. This article represents the authors’ personal opinions and not those of their employers.

An adapted version of this article appeared on the Dialogue Review website.