Evidence-based decision-making leads to better outcomes than decisions based on instinct alone, no matter how experienced the decision-maker is.

Everyone who’s read Blink, Malcolm Gladwell’s best-selling treatise on instinct, is aware of the raw power of human instincts. In the book, Gladwell describes doctors who can instantaneously identify a patient with a life-threatening condition in a hospital queue, or antiques dealers who can spot well-constructed fakes with only one glance. Professor John Gottman, meanwhile, can predict with 90% accuracy whether married couples will stay together after meeting them for just a few minutes.

Gladwell’s theory is that experts think without thinking – that their instincts are often more reliable than analysis of empirical data.

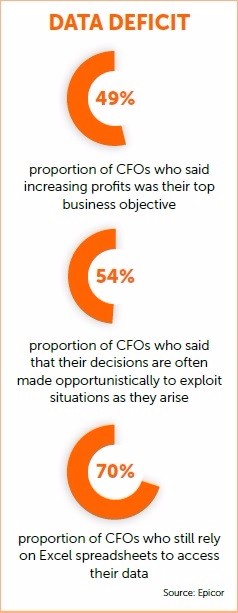

But new research suggests that those who don’t allow their instincts to dominate them, and consult hard data, make better decisions. When Redshift Research surveyed chief financial officers (CFOs) in the UK, it found that half of them relied upon gut instinct to help them make decisions. Much of this was down to circumstance – a dearth of empirical evidence coming into their companies, or the inability of their teams to analyze it properly, meant their gut was all they had. “In the absence of any data, many had little choice but to go with their instinct,” says Malcolm Fox, vice president of product marketing at Epicor, the Texan software company that commissioned the research.

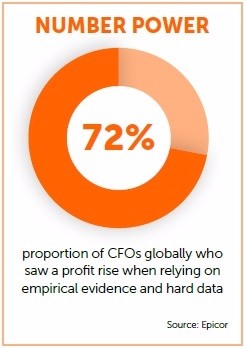

But instinct only got the CFOs so far. The research revealed that CFOs who based their decisions on empirical evidence, rather than relying purely on their gut, made more money. “The simple truth is that decision makers who were on top of the numbers were more profitable,” says Fox. “Gut instinct has its role but it’s much better used in concert with the data rather than instead of it.” The Redshift study and Gladwell’s findings aren’t mutually exclusive. Gladwell suggested that experts acting on instinct were in fact instantaneously calling on the empirical data their brains had stored from thousands of previous experiences. Leaders in their field had a knack of separating the instructive elements of their experiences from the stuff that didn’t matter so much, enabling them to make good decisions with relatively little new information. As Redshift found, instinct can be a useful tool, but it ought not be the primary driver of a decision. “Lots of the CFOs we surveyed thought that instinct and intuition played a key role in their decision making,” says Fox. “But the most effective of them used this to guide them around the data – rather than fill in the gaps where they lacked any information at all.”

David Molian, director of the business growth and development programme at the Cranfield School of Management, is a world expert on the performance of owner-managers in growing businesses. Along with psychologists from France’s University of Toulouse, Molian examined the relationship between owner-managers’ confidence in their own judgment and their sales and profit. He discovered an interesting pattern: owner-managers who were very confident in their own instincts tended to exhibit poorer business performance. By contrast, those owner-managers who had less faith in their own instincts tended to have greater business success. “Owner-managers with less confidence in their own judgement were much more likely to consult the data and take advice,” Molian tells Dialogue. “In business, it pays to look at the evidence before you leap.”

Gut instinct can help when an owner-manager is in their comfort zone – trading in areas they know well, with well-established companies and long-standing clients. Growing businesses are different – here science is more successful than art. “Because their businesses were growing, the owner-managers we spoke to were probably likely to be venturing into new areas beyond their own knowledge,” says Molian. “The message is not to ignore your gut instinct but – particularly if you are entering into new territory – to validate it with data and the advice of others.”

This golden data mining is harder than the headlines about big data might have you believe. If this is the data age, it still doesn’t feel like it to many CFOs: well under half (43%) told Redshift that they had “good visibility” of financial information. In certain Industries – such as engineering and manufacturing – financial IT systems were so basic and/or out-of-date that instincts were pretty much the only game in town.

All industries seem to suffer from data Luddism – 70% of CFOs remain shackled to Excel spreadsheets despite the raft of specialist business systems and data applications available. “Companies need to make data analysis easier, to encourage more CFOs to become involved,” says Fox. He suggests that CFOs investigate enterprise resource planning software, which collect, manage and interpret company data from a wide range of company functions.

The analysis problem A 2014 report from the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) found that Fox’s point was key: access to raw data wasn’t the problem so much as access to authoritative analysis of it.

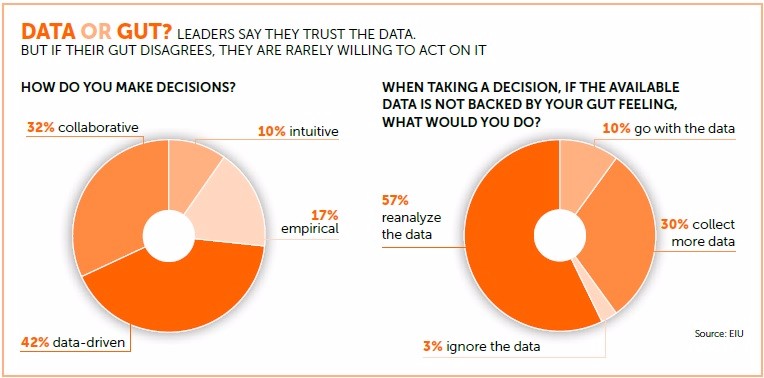

In the absence of reliable and simple ways to interpret information, leaders resorted to doing things collaboratively, involving more people in decisions to share the risk. There was little evidence that this improved the quality of decisions: respondents to the EIU were divided as to whether outcomes were better or worse when a collegiate approach was taken. And instincts still mattered a great deal to EIU respondents: nearly three-quarters of respondents said they trusted their own intuition when it came to taking decisions, even among those who told the EIU they always analysed the data before making a call.

These apparently paradoxical findings may betray a greater truth: if the data failed to match leaders’ instincts, they allowed their gut to override the evidence (see infographic, data or gut).

The EIU researchers discovered that experimentation with the data was crucial: companies that were willing to risk “failure” on trials performed better in the long run. This may have helped leaders “overcome” their gut instinct – which could at times lead them astray, causing them to miss out on opportunities or avoid mistakes.

Dan Humble, director of insights and research at Alliance Boots, told EIU researchers that he too would reanalyze the data were his gut to disagree. If the data contradicted his intuition, it could be sign that something had gone wrong with the collection or delivery of the data. “You’d want to check that the information is correct,” he tells the EIU. “It might be that your perspective isn’t wide enough, and you need some more data about the market, for example, to understand the context of your own data.”

Perhaps those who let their instinct challenge the data are approaching business the wrong way round. Data is king. But your instinct can be a useful tool for challenging it, Humble adds. Instinct can act as a warning that your data is weak, haphazardly collected, or badly analyzed. But if it’s been properly checked and tested then it may just be that your instincts are plain wrong. “If you’re confident the data is right and you’ve understood how it fits in, you’ve got to act on it,” says Humble.

Back at Cranfield, Molian emphasizes that our instincts are limited in power. They are likely to guide us well in fields we already know well rather than new ventures and areas of business expansion. “Relying wholly on gut instinct may give you a decent start in business,” says Molian. “But it’s unlikely to sustain you for the long haul, especially if you have ambitions beyond what you are already doing.”

ILLUSTRATION: CAMERON LAW

An adapted version of this article appeared on the Dialogue Review website.