With new trade barriers set to dramatically change the terms of global trade, how do finance leaders regard the outlook for the US economy? We sat down with Fuqua professor John Graham to find out

“Without data, you’re just another person with an opinion,” as famed management theorist William Edwards Deming once said. Those looking to understand business sentiment in the US – and specifically the outlook among its leading finance executives – have few sources of data as rich and well-regarded as The CFO Survey.

Started in 1996 by Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business, The CFO Survey is today a partnership with the Federal Reserve Banks of Richmond and Atlanta. At its heart is a survey panel that spans firms ranging from small operators to Fortune 500 companies, across all major industries, with respondents including chief financial officers (CFOs), owner-operators, vice presidents and directors of finance, accountants, controllers, treasurers and others with financial decision-making roles. That makes it a fascinating source of insight on market conditions and the road ahead for US businesses.

Dialogue sat down with John Graham, the D Richard Mead professor of finance at the Fuqua School of Business – who has directed The CFO Survey since 1997 – to quiz him on the latest data and the impact of an uncertain and highly changeable business environment.

Tell us about the findings emerging from the latest installment of The CFO Survey. How do CFOs regard the outlook?

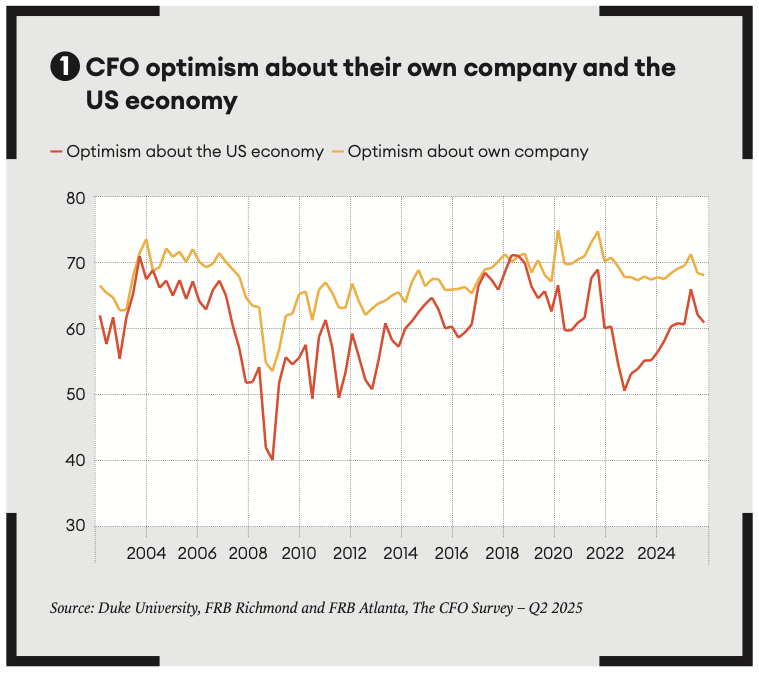

The CFO Survey’s Optimism Index has two components [see Figure 1]. One is, how optimistic are you about your own firm’s financial prospects? And the other measures optimism about the overall state of the US economy. Typically, the ‘own firm’ optimism is above the optimism for the economy, because people are generally that little bit more confident in their own firm’s performance. But this is where things get interesting.

If you go back to President Trump’s first term, the prevailing view was that he was coming in as a pro-business figure. The overall economy optimism score soared: it caught up to, and even briefly surpassed, the own-firm optimism. At that point, CFOs were thinking: “OK, we’re not quite sure what’s going to happen here for our firm. But we think this is going to be good for the overall economy.”

This time around, there was a similar initial reaction after the election. Businesses were thinking, “We know this guy a little bit better than we did the first time around” – and there was an increase in whole-economy optimism, along with a smaller increase in own firm optimism.

But look at what’s happened since then. There weren’t any great moves after President Trump’s inauguration in January 2025. Then ‘Liberation Day’ came, in President Trump’s terminology – the day in April when he announced his tariffs for the first time. It was a shock for the economy. Economy-wide optimism fell quite a lot; own-firm optimism also fell, though not by as much. So we now have a situation where CFOs are becoming more concerned about the overall economy.

Their confidence about their own prospects has softened too, although most have plans to handle what’s happening. They can stock up on inventory, or shift suppliers, and so on. I’d describe the outlook in the last few months as: “We don’t like it, but we think we can limp our way through this.” Note that CFOs never predicted a recession this year. Jamie Dimon [CEO of JPMorgan Chase] did, and some economists did – but what we saw in The CFO Survey was that the mean post-election expectation for GDP growth of 2.3% fell back to 1.4%. That’s a significant drop, but it did not go negative, meaning that CFOs did not anticipate a recession.

So far, CFOs’ assessment has proven pretty accurate – that’s about where we are as an economy. And other indicators, like the employment numbers, are not as bad as people feared. That’s not to put a gloss on things, but CFOs’ attitude has been: “We can get through this.” And that seems to be right.

One of the striking findings in the data over recent years was the divergence between own-firm and whole economy. Was that a temporary change – or does it say something more profound about leaders’ views of the economy and the uncertainty facing business?

That’s a great question. I think it’s probably temporary – we’ve been asking this question for decades, and optimism goes up and down – and you look at what was happening in the economy. During the past five years, we had Covid, then increased inflation and high interest rates, which created a lot of concern. Even when we rounded the corner, there was this lingering concern about how long we could withstand high interest rates. But we were heading in the right direction until the tariffs shocked us back in that negative direction.

Now, has the US economy fundamentally shifted? Are we going to drive all our scientists away, and so on, in the long run? Only time will tell. I do think it’s likely that economy is going to ‘putter along’ in the moderate term, more so than before.

Certainly, in the short run, CFOs are very concerned about the tariffs. There are two components to that. One is the tariffs themselves – and the second is uncertainty about the tariffs. That’s reflected in our data. We ask CFOs an open-ended question: “What are your top concerns?” We give respondents a blank line, where they can write as much as they want; most put in maybe two concerns, sometimes three. This “blank line” approach is better than giving people a list where they can just check things off – our approach tells us what CFOs are right now thinking about.

Now, for years, one of the top concerns was labor: its quality and availability, and the challenge of retaining those employees that businesses really value. A couple of years ago, concerns about inflation and interest rates increased, to equal or even surpass concerns about labor.

But what’s happened in 2025? Tariffs are the number one concern, by far. They’re the biggest concern we’ve ever heard from CFOs, over the 15 years we’ve asked this question.

The extent of the uncertainty that confronts leaders around policymaking and the overall health of the economy is striking. What do you see as being the best strategies for business to find their way through this?

Well, one thing you can do is pass the costs along. Overall, 41% of CFOs expect to pass on tariff-related costs. This could have a big impact: of the CFOs who say they’re directly affected by tariffs, the planned pass-along rate is 80-100%. Of course, there’s always a risk that if you raise prices sharply, demand falls, and you may have to pull price back down somewhat. But at least as an initial step, these tariff-affected firms would like full pass-through on tariff-related price increases. Other firms might pass along costs to a lesser extent – so there’s a substantial portion of the economy saying they’re going to raise prices.

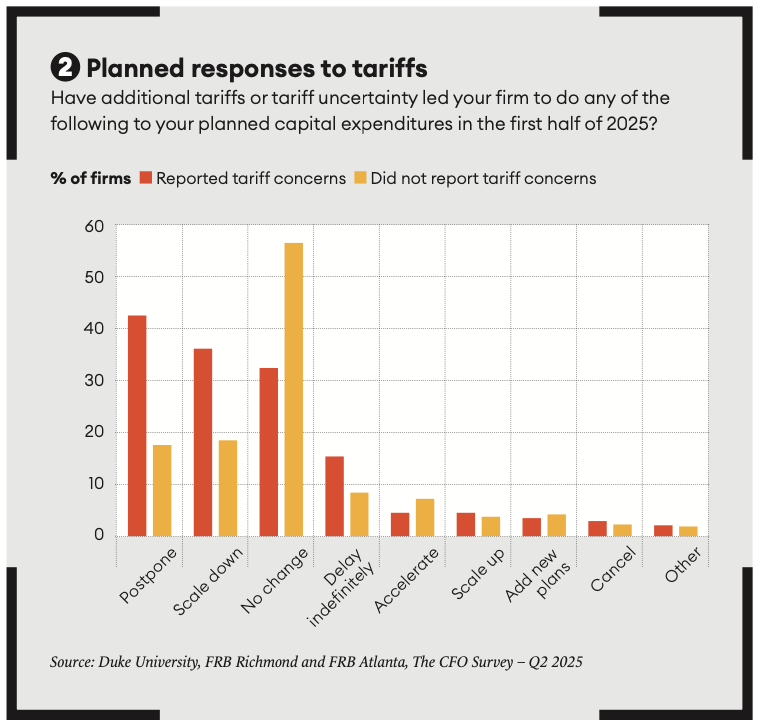

A second option is to cut expenditure, which we’re seeing emerge as a primary response to the tariffs. Capital spending, for example, can be postponed, scaled down, delayed, or outright canceled. Among those businesses that are directly affected, 55% of CFOs say they’re doing one of those things to reduce capital spending. In the manufacturing sector, it’s 59%.

We’ve also seen hiring plans for this calendar year falling. They dropped from the end of 2024 into the first quarter of 2025, and again into the second quarter. CFOs see hiring rebounding somewhat next year, so there’s a sense that this year is going to be pretty challenging, but they expect 2026 to be a little better.

Another play is to stay the course with your core business focus. If you lose track of what you do, you’re in trouble – so leaders might be more cautious. They might decide it’s not the right time to expand – if anything they might pull back, because they’re focused on the short term. And the other thing is to refocus on taking care of your customer. It isn’t necessarily what a finance person naturally thinks about – but it is likely to be super important.

Given how companies are cutting back on capital expenditure and investment, has the short-term become the enemy of the long-term?

Absolutely – and it comes back to uncertainty. Economists often talk about uncertainty and like to debate whether observed effects are the result of the ‘bad thing’ that’s happening or uncertainty around that thing. In this case, I’m comfortable saying that we’re seeing both. The tariffs are generally viewed as not positive – there are some businesses who like them, but generally, they’re not seen as positive.

On top of that, there’s the uncertainty: how big will the tariffs be when the dust settles? Will some be removed, and others increased? Anecdotally, CFOs are saying: “I want the politicians to just make their decisions and tell me what I’m dealing with, so I can start trying to plan around it.” Companies can change their supply chain if a tariff is in place, for example – but if they think the tariff could suddenly be removed, then maybe they won’t make changes, and maybe they won’t make drastic moves on reshoring.

That leaves CFOs feeling they have to tread water for now. They’re going to see how this plays out, and then be decisive when they have more information.

What’s your sense of how organizations are investing in AI, given its potential impact on corporate productivity – and on costs?

We’re actually asking CFOs about this in the coming quarter, so that will be out in September 2025. We’re seeing a lot of spending on AI in this calendar year and next, but my sense is that while some companies have found AI super-helpful on a few things, a lot of companies are still trying to find the right way to use it. Eventually, you’d think a lot of companies will use AI to cut their cost structure, but I don’t think we’re there yet; there’s still a lot of concern about its imperfections.

So I don’t think AI is affecting employment in a big way at this point – not any more than earlier phases of automation, when we saw things like robots in factories or warehouses. Certainly, that’s what has happened in manufacturing. Even if production comes back to the US, it’s not going to be like the old days, due to fewer human employees and more robots. It could be great for GDP, but not necessarily for employment.

At the same time, even though you might read about layoffs at some companies, we still see other firms really trying to hold on to employees. They know that they could lay people off now – but if the economy rebounds, they may not be able to rehire them. Where companies have got good people, they want to keep them.

You mentioned the expectation among CFOs that the economy should improve in 2026. If that’s going to happen, what are the key things to look out for?

Outside of the survey data, I’d look at things like consumer spending. It’s a huge portion of the US economy, so if that weakens – because people lose their job, or interest rates stay high and mortgage payments go up, or any reason like that – then that introduces a whole new layer of risk to the overall outlook. People have largely spent any payouts or credit they got during Covid, so going forward, consumer spending is definitely something to keep an eye on.

On the positive side, if the US strikes a number of international trade deals and interest rates were to come down, I think there’d be a little more confidence. There are possibilities that if we get through the tariff turmoil in a reasonable spot, and the Fed starts to feel comfortable reducing interest rates, things could pick up.

That said, there is growing concern about the budget deficit – if the Fed cuts interest rates that could help, but a lot of people think the deficit will start to bite soon. Nobody knows if that’ll be this year, next year, or the year after that – but if the federal budget doesn’t get straightened out, that could be a medium-term risk.