Developing a rubric for culture change can help leaders win buy-in, as an example from the US Navy shows.

When a team is falling short on its targets, a new leader is often brought in with a mandate to improve performance or boost contributions to the bottom line. My time in the US Navy taught me that focusing on the numbers, while important, is not enough to unlock a team’s ability to reach its maximum potential. The key to improving performance resides in the organization’s culture. In order to build trust, balance the needs of the workforce with organizational success and stabilize the team in times of opportunity and crisis, leaders need to ‘own’ culture at a level well beyond the superficial.

Edgar Schein’s classic definition of culture is: “A pattern of shared basic assumptions learned by a group as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration.” In other words, it’s a product of combined learning over time. For institutions like the US Navy, the core of organizational culture has formed over centuries. For giants like Amazon and Facebook, the time frame is years, or decades at most. For new companies and start-ups, the learning is only beginning; the core is still forming. In all three contexts, leadership builds and tends to that core.

A rubric for change

During my time as the Navy’s head of HR, our team had the seemingly impossible task of implementing a data-driven approach to talent management that senior leadership could leverage to improve recruitment, training, distribution and retention across the Navy’s 400,000-plus uniformed workforce. The data management system we had was decades old. It was not responsive to economic trends, or to our sailors’ desires. A change in technology and policy was needed. It started with culture.

Driving change in human resources and keeping our customers – sailors – informed required a common framework across the HR team: one that engaged heads and hearts before people put their hands to work. That wasn’t easy to achieve, and we were not always successful, but consistency and clarity eventually succeeded in persuading the team to buy into the approach, ultimately making it their own vision for enacting future change.

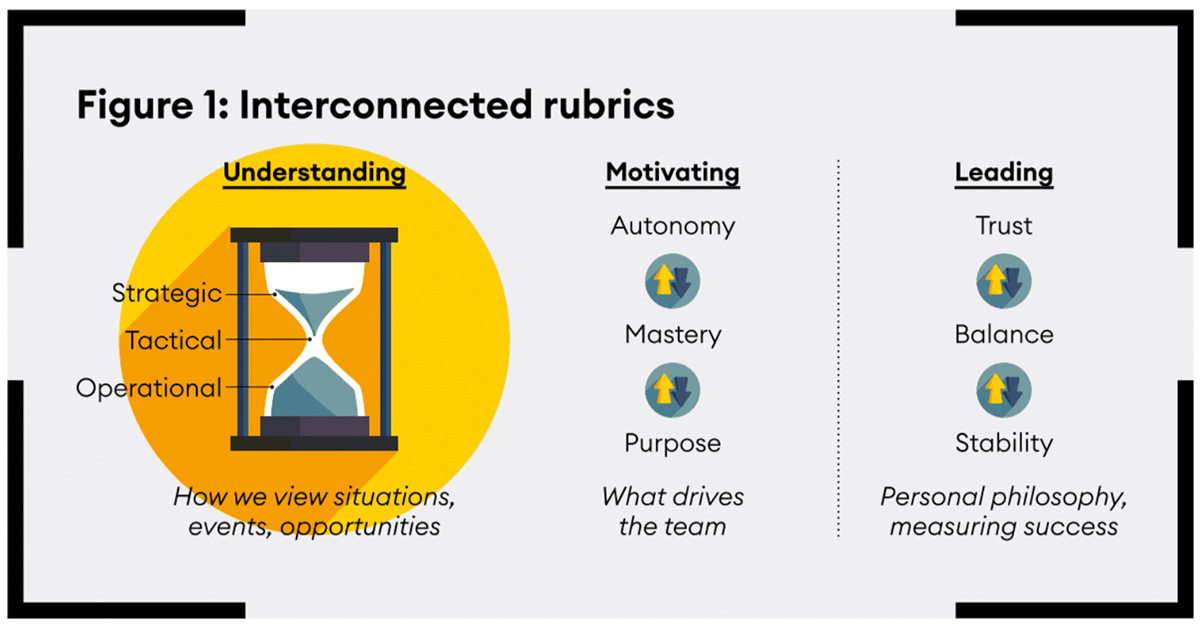

Central to this success was a common rubric for understanding, motivating and leading, similar to that shown in Figure 1.

It had three elements. First, our HR team adopted a shared strategic, operational, and tactical view of the issues affecting the workforce. We used an hourglass motif to remind leaders at all levels that where you spend your time matters. A leader should start the day at the top, on strategic issues, and ‘flip’ the hourglass periodically to assess if the team was still oriented towards strategic goals. It was also a reminder to consider the different levels of challenges. When they were in the middle – the tactical level, where the velocity of time or issues is greatest – leaders might miss key aspects of the bigger picture at strategic and operational levels.

Second, to keep the team motivated, we adopted another rubric influenced by business author Daniel Pink. It underlined that the team had to feel that change was happening as a result of their efforts and talents, not because they had been directed to carry out a set of disconnected tasks. Our third rubric served as the yardstick for our policy-making and measures of progress. If our work didn’t enhance trust, maintain balance and increase stability, we knew a different approach was needed.

Creating a rubric that works for you

Schein writes: “Human minds need cognitive stability and any challenge of a basic assumption will release anxiety and defensiveness.” How, then, to achieve that stability? Books, blogs and articles on culture and behavior can be enlightening, but they seldom explicitly answer your team’s challenge. It can take a hybrid approach of theory and personal experience to fully understand and leverage the strength of your team’s culture: I drew on the lessons of my youth playing team sports and my early-career experiences leading sailors to help shape the rubric used by our HR team. Instead of simply emulating or repeating the calculus of others, it is important to recognize that each new leadership opportunity is unique. It is essential to contextualize; to create a personal rubric that can help you understand, motivate and lead your team in a way that fits your distinct circumstances.

Three points are key to making it yours. First, incorporate a variety of themes. Leaders that pick and choose from many different writings are multidimensional and more complete. Second, make it easily understood – by you and by your team. The best thinking in the world is useless if it doesn’t resonate. Third, be practical. If your rubric doesn’t help you or the team work through day-to-day issues, as well as crises or times of great opportunity, it may need work. It has to be more than a slogan that reads well above the door, or on the company website: it should make you a better communicator and clearer thinker.

Having interconnected rubrics can help leaders define their problem or opportunity, build team buy-in, and evaluate the progress and effectiveness of decision-making. A common approach to situational awareness, team motivation and change management provides cognitive stability and reduces the perception that basic assumptions are being challenged.

Schein was absolutely correct when he wrote that “the only thing of real importance that leaders do is to create and manage culture.” Otherwise, it simply manages you. There is nothing quite like seeing the lights come on bright when a majority of people across an organization recognize they’ve cultivated a culture geared toward results. Make it a team and leadership priority, day in and day out, and you will see the lights come on in your organization, too.