Organizations thrive when they meet humanity’s hardwired needs for purpose and empathy, write Sudhanshu Palsule and Michael Chavez.

The last evolutionary upgrade to the human brain was the development of the pre-frontal cortex, approximately 70,000 years ago. It set us apart from all other species and, over time, allowed human cultures to take shape through the medium of language. We developed the capacity to imagine alternatives to the realities before us and, freed to think of ‘what could be,’ humankind began transforming the environment to make it more amenable for survival.

That capacity for imagination brought with it the complex need for purpose. It has been one of the most powerful vectors of our evolution. Not being satisfied with what is, but having a need to know why, has driven extraordinary developments in almost every aspect of human life in every civilization around the world, from philosophy, science, technology and medicine, to literature, art and poetry. It allowed for group cohesiveness, making it a powerful tool for survival in hostile environments. As a result, purpose is hardwired into our consciousness as an evolutionary mechanism. The need for purpose is a powerful human need.

Another critically important vector emerged in response to the growing complexities of social relationships: empathy. The human empathetic function was sculpted by the computational requirements of dealing with a hostile environment and the need to interact and communicate with others. Empathy relies on a sophisticated coordination between our sensory systems (detecting feelings) and emotional systems (mirroring emotions). When our tear ducts involuntarily produce tears at the sight of another’s suffering, it demonstrates how an ancient adaptive ability to empathize continues to throb inside the human brain.

Changing the narrative

The emergence of purpose and empathy as vectors of human development was a major evolutionary breakthrough. They still play a profound role in human behavior today, yet where have they been in the dominant discourse surrounding economics and business in past decades? Individual interests were put before anything else and we became dehumanized to our natural environment and the wider communities in which we exist. The Covid-19 pandemic is a stark wake-up call for us to challenge the various economic, political and leadership practices that are associated with a dehumanized discourse.

Even before the virus’s outbreak, it was clear that the old individualistic narratives had reached the end of their usefulness, for two key reasons. First, the very environment that keeps us alive has over-shot the limits of sustainability. Second, we now live in a complex and interconnected world that is wired up as a gigantic network. The us-vs-them mythology is outdated; we have no choice but to rehumanize our leadership and bring purpose and empathy back into the way we lead and govern. This means transforming our organizations to operate from the axes of purpose and empathy, with a view to creating a meaningful impact on the external environment of nature, market and society, and in our workplaces.

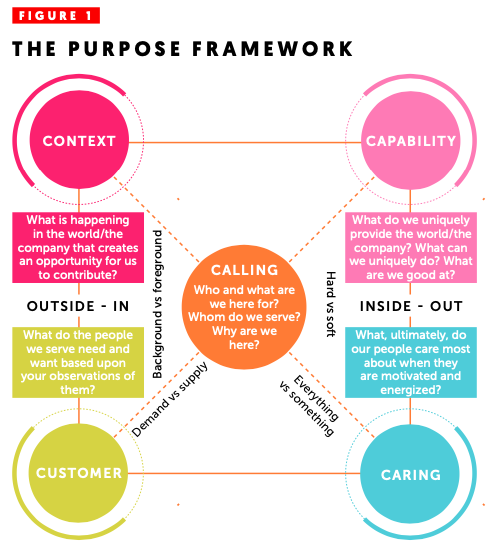

In our new book Rehumanizing Leadership: Putting Purpose Back into Business, we explore how leaders can find their personal purpose, create team purpose, and help those they work with to find purpose in their jobs – what author Daniel Pink calls the “small p” purpose. But of course, leaders also carry responsibility for developing purpose for their organizations as a whole. Developed on the basis of our work with a wide variety of organizations around the world, our purpose framework provides a model for building purpose in a systemic way.

As American engineer and business consultant W E Deming famously said, “your system is perfectly designed to give you the results you’re getting.” It is time to change the system.

The Purpose Framework

Harvard Business School professor Rosabeth Moss Kanter has showed that the success of great organizations is based not only on their economic logic, but also on institutional logic. A company’s value is measured not just by short-term profits, but by how it sustains the conditions that allow it to flourish over time. Great purpose-led companies get their institutional and economic logic right by developing four clear perspectives.

1 Context The environment we are operating in

2 Customer The recipient of our service and/or products

3 Capabilities What we are capable of providing

4 Caring What we stand for

The first two perspectives come from being externally focused while the second two are internally focused, in close touch with the ‘inside’ of the organization and its people. Together, they act as necessary constraints on purpose, helping it to emerge at the center, informing and shaping not only the strategy of the organization but also its processes, systems, tools, products and services.

The external perspectives: context and customers

Walter Isaacson’s biography of Steve Jobs reveals all the shades that the genius possessed. It includes one telling revelation that is highly relevant to the external perspective. Jobs’ Wednesday morning meetings were left pointedly unstructured, without an agenda or slides. Instead, they began with a simple question: “What’s next?”

By continually developing its perspective on what was happening in the environment, Apple was able to stay ahead of its competitors. When it came to digital technology, Jobs saw an opportunity where Sony saw a threat. His reading on how diverse industries were converging allowed him not only to build the iPod, but to develop iTunes, changing the way we listen to music. His famous quip was: “People don’t know what they want until you show it to them. That’s why I never rely on market research. Our task is to read things that are not yet on the page.” Jobs was a master at understanding the external perspective and picking up weak signals.

The lessons? “What’s next?” is not a question you ask at the occasional off-site, but something that gives us the ability to look at our organization from the outside in. Yet unless you make the time for this work, it is easily ignored. When we ask senior clients, “When was the last time you met your customers?”, we are often met with an embarrassing silence. “What’s happening in the world that is currently occupying your thoughts?” is another key question. Are you reading enough? Could you comment on the latest geopolitical changes? Great leaders draw the world in through large windows that they keep deliberately open. Free up time for unstructured work like customer visits, regular ‘what’s next?’ meetings, building your network, and taking part in external activities. This is not something you do outside your regular work: this is your regular work!

Key questions in the external perspective:

Context

- What is the environment that we are operating in?

- What is changing?

- What is happening at the edges of our industry/field?

Customer

- What do the people we serve need and want in their experience of life?

The internal perspectives: capabilities and caring

The internal perspective is about an awareness of two critical factors: your capabilities, and what energizes your people. There is no better way to energize people than to connect them with how their work “meets people’s enduring needs,” in the phrase of transformational leadership guru James MacGregor Burns.

We once ran a large-scale leadership program with a well-known insurance company. Engagement scores were not looking great and morale was faltering. The lack of energy in the office was palpable. Our interviews revealed that most of the company’s employees had never met a customer – so we brought four into the office for a half-day event. One was a woman called Sally.

Sally told the story of how, 15 years ago, she received a call from her husband’s office informing her that her husband had died of a heart attack. As she put it, her whole world collapsed around her. She had no idea what to do. After some days had passed, Sally’s sister asked whether the husband had insurance. They managed to find the papers and, with trembling hands, Sally made a phone call. She told us of the person who answered and, with great care and empathy, went through what Sally was entitled to – and, she felt, went out of the way to provide comfort. Sally ended her story by saying, “Thank you, whoever you were. Thanks to you, I was able to put my kids through college.”

There was not one dry eye left in the room. Suddenly, there was a palpable sense of purpose in what, just minutes before, had been a bland office devoid of energy or emotion.

The late Sumantra Ghoshal, scholar and educator, referred to this as “the smell of the place.” It is what gets people energized, and it is a critical component of the purpose framework.

Capabilities

Understanding capabilities is not as easy as it may seem. The challenge is to understand what you, uniquely, provide the world, and to become critically aware of your relevance.

When Lara Bezerra took over as the country head of India for Roche, she realized that she had to clarify the purpose of the entire business in India. At a strategy workshop with the leadership team, Bezerra asked two thought-provoking questions. First, what would Roche need to change as a whole to deliver according to plan in the year 2030? Second, she asked: “If Roche sells this company in India and we bought it, what would we do?”

The discussion generated a range of culture principles for how the company should be: bottom-up, self-organizing, emergent; flexible, responsive, on the edge; ‘like a jazz jam session’; vision-centered, value-driven; holistic; playful and able to fail; deeply green, with concern for social impact and humans; using sustainability and systems thinking; thriving on diversity; embracing ‘both-and’ thinking. It was clear that achieving this was not going to be easy. That shaped Bezerra’s approach: “There were times when we had to stand on the stage and say, ‘we don’t know.’ We believe in people, but we had to be vulnerable to our people and say we need your help.” She went on to redefine her role as the chief purpose officer.

Key questions in the internal perspective:

Capability

- What do we uniquely provide the world?

- What can we uniquely do?

- What do we need to get great at?

Caring

- What ultimately do our people care most about when they are motivated and energized?

Finding purpose

As Figure 1 illustrates, the four perspectives in our Purpose Framework create four axes, defining the space in which purpose can be found.

Axis 1. Context and Caring – Making the choice to focus on what we really care about and how that is relevant to what is emerging in the environment and the world around us

Axis 2. Customer and Capability – Narrowing the space between what customers need/want and what we are great at. What do we need to get better at?

Axis 3. Context and Capability – Making the choice between what is happening outside and what we are uniquely able to provide

Axis 4. Customer and Caring – Making the choice between what customers need/want and what brings out the best in our people

We describe the process of finding purpose as beginning with ‘excavation’ – a term which we heard used at ANZ Bank and American Express. As leaders begin to have conversations about purpose across their organization, they slowly begin uncovering their purpose at the center of these four axes. It culminates with the core question: “Why are we here?”

Purpose is oblique, in that it emerges when we start taking away what it is not. Asked how he had managed to sculpt something as beautiful as the statue of David, Michelangelo is reputed to have said that David was always in the marble – all he had to do was to take away the bits that were not David. Leaders face the same challenge when it comes to finding purpose.

The case for optimism

Faced by a range of discouraging global trends, particularly in politics, some people understandably feel that the future is bleak for our vision of rehumanized leadership. We firmly believe otherwise. We would argue that we are in fact seeing the last stand of the old narratives. The change we need will not happen overnight, and it will not be easy, but we should nevertheless be optimistic about the future. The two vectors of purpose and empathy that are embedded in our pre-frontal cortex are our resources for leadership in the 21st century. Putting those vectors back at the heart of how we do business is one of the overriding challenges facing leaders today.

— Sudhanshu Palsule is an award-winning educator and CEO adviser. Michael Chavez is global managing director of Duke Corporate Education. Their book, Rehumanizing Leadership (LID Publishing), is available now at rehumanizingleadership.com.