A former City of London Police counterterrorism chief explains how introspection has helped him find his inner resolve and stay calm in crisis situations.

In my three decades as a police commander, five years of which were spent in the nucleus of the City of London Police’s counterterrorism operations, I have discovered that the most important tools you have are within you, learned not just as a student, or on the job as a professional, but through a series of experiences beginning as a young person. Introspection doesn’t come naturally to many leaders – we are trained to be outward-looking, to direct others, to command and to serve. Yet prolonged periods of deep self-reflection are absolutely crucial to being able to cope in a crisis.

You have to spend a lot of time finding your inner resolve

Preparation for most people simply means training and experience. They are important things that every caring organization should promote. But to understand where your inner resolve comes from, you need to spend long periods looking inward. When I was a young police officer, I sat down quietly with everything turned off, all outside influences shut out, and said to myself: “I made a series of decisions today and they were lifesaving. Where did that come from? What did I rely on for that 18-hour shift? The energy I found to command and sometimes to challenge my senior commanders, what part of my life experience gave me that?” It’s not just your passion for the job that drives you. It comes from something deeper.

You cannot start looking inward after your first crisis

You need to be continually proactive and prospective in your introspection. Do your inner audit before you face your first crisis as a leader. Look inside yourself, re-examine your childhood and career experiences and how they shaped you. Unless you look inside, and understand where your resolve is coming from before your first crisis arrives, you will only respond to that crisis with half your potential ability.

Everything you experience in life contributes to your crisis response

Through childhood, through school, through your junior stage, through your twenties, thirties, forties, however you got there, your total ability to respond when the crisis happens relies on what has happened to you up to that point.

Who were your role models at school? Were your teachers encouraging? Was your father dogmatic? Did you experience trauma as a child? What were your associations at school or college? Were they political associations? Were you a Young Conservative or part of the Labour Movement? Did you join the Boys’ Brigade or the Girl Guides?

All those people around you are shaping you, influencing your beliefs and how you respond. Consider how your religious faith, or lack of faith, has shaped you. Then there’s your choice of job. Once on the career path, you end up in a narrow funnel, surrounded by people like you who share your preferences. That narrowing is shaping you in a fundamental way too.

You gain qualities from other people

If you have an ability to defer, you learned it from being around people you saw defer well and at the right times. If you have an ability to command, you picked it up from commanders who once commanded you expertly. If you are compassionate, you have developed that skill from someone from whom you have witnessed compassion.

Try to identify those people who have influenced you because you admired them. You are emulating them without your knowing it – it’s important to work out who they are and why you admired them.

When you are responding to crises there is no time to reach for the manual

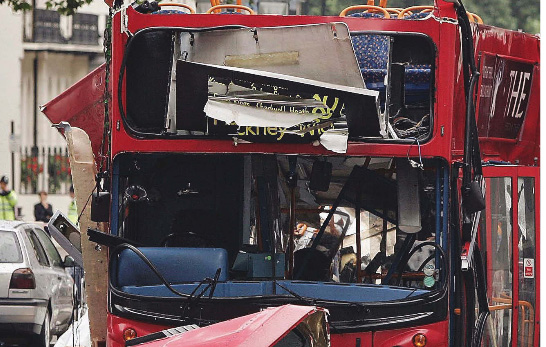

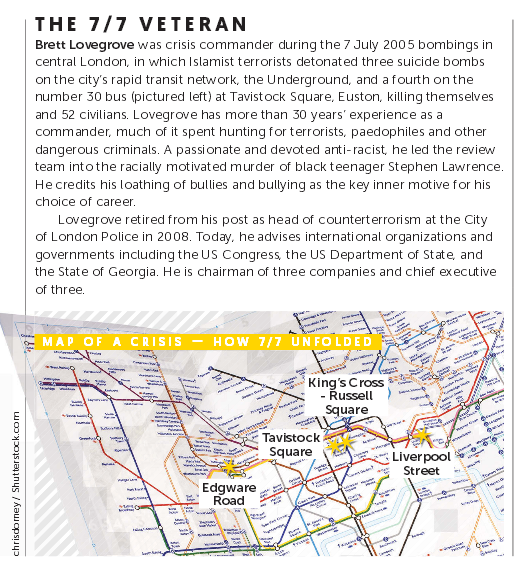

During the 2005 London bombings, I only reached for the manual in the late afternoon of the first day. The only reason I did so was to check what I did against the textbook, to ensure I had done everything I should have done. In that case, the manual backed me up.

But documents can’t prepare you for every kind of crisis. You need to know enough about yourself to trust yourself to make the right calls, so you can be confident that you will perform, whether or not you have been trained for, or have experience in, those exact circumstances. You listen to your advisers, who will tell you what the manual suggests you consider in particular situations. But you can say, “Yes, okay, I understand that, but this is not the time for that option, I’m not going to do it like that now, I can probably consider that later.” The manual is only there to make sure you haven’t missed something huge.

Feedback tells you what your crisis toolkit lacks

Your friends and colleagues might start feeding back by feeling that they know more about you than you do yourself. When they comment on your actions, or elements of your personality, it’s because those acts or traits are visible to them. When people comment, try to understand why you are missing certain tools. It’s important to reflect and say to yourself, “I see why I acted like that, it’s because I haven’t had that experience, I can’t hang my hat on any one person or thing that I have known and therefore I don’t have that tool. What do I need to do, with whom do I need to work to get it?”

Don’t try to lose your emotional baggage

You shouldn’t try to dispense with the bad parts of your psychological makeup. With introspection, you can get to a point where you know why you are the way you are, even though you may not be particularly proud of it.

If you shed the psychological baggage, you will never be able to use it as a reference point. You need to be able to say, “that’s not a great part of my persona.” Be aware of it – if you got rid of those pillars of awfulness, you wouldn’t be you. You would be knocking out one of the mainstays of who you are. So understand your downsides, but don’t rely on them. Identify and rely on the good stuff.

An adapted version of this article appeared on the Dialogue Review website.