Leaders should be able to show vulnerability – but it must be balanced with the core competence of leading others.

My parents fled communism with no passports and no money. They both lived in the Republic of Georgia, not too far away from each other, yet they only met in Italy – a place that many émigrés went as a transition hub. The only valuable that my mom had was my grandmother’s family heirloom: a half-carat diamond that she had melted into the handle of a knife to avoid detection by the KGB. All other valuables were stolen or confiscated. After Italy, my family arrived in Australia, which is where I was born. They didn’t speak English, and my mom, dad, aunt, grandfather, grandmother and great-grandmother did a variety of jobs to make ends meet. These included scrubbing toilets at a hospital, cleaning the floors of a chocolate factory and driving taxi cabs – whatever was needed to survive.

Eventually my parents and I landed in Los Angeles, where my dad became an aerospace engineer and my mom a successful therapist. My dad is a quiet thinker who speaks very little and worked long hours. He modeled the power of never giving up. But when my dad lived in the Soviet Union, showing emotion, or indeed any vulnerability, could lead to trouble. Like many other immigrant fathers, he taught me that showing emotion of any kind was a weakness. Vulnerability was dangerous and should be avoided at all costs. My mom showed me the value of emotional openness but as a young boy, I grew up emulating my father.

In my own education and career, I relentlessly pursued success – until one day, at home with my family, I had a panic attack, out of nowhere. More followed. I didn’t know what they were, or where they came from. For the first time in my life, I felt extremely vulnerable. I didn’t know where to go or what to do. It turned out that a major cause for those panic attacks was the fact that I was writing a book on vulnerability, a feeling I had repressed for most of my life.

Understanding vulnerability

I decided to connect my own personal interest and experiences of vulnerability with my ongoing leadership research. After interviewing over 100 chief executives and surveying 14,000 employees around the world in partnership with HR consultancy Development Dimensions International (DDI), I discovered that there is a profound connection between vulnerability and great leadership. Leading with vulnerability is the single most impactful thing you can do to create connection and drive performance, if – and this is key – you know the right way to approach it.

Some of the questions I asked these CEOs were deeply personal. What makes you feel most vulnerable, and why? What other attributes do leaders need to help unlock the power of vulnerability? How can you be vulnerable at work without being perceived as being weak? Have you ever been vulnerable at work and had it used against you? What’s the impact of being a vulnerable leader? Do you think about the intention or purpose behind being vulnerable?

What happens if you work with people who don’t believe in being vulnerable?

Our discussions were often so deeply personal that several CEOs asked to be made anonymous in my book. They shared stories and insights with me that they had never shared before. I am grateful for their transparency and willingness to be vulnerable with me. I laughed and cried with them. I shared all sorts of emotions and in-the-moment discoveries that I will forever be grateful for. It was through their openness that I was able to start answering the questions I had about vulnerability.

Like you, I had heard of vulnerability and had an idea of what it was. As Brené Brown puts it, vulnerability is “uncertainty, risk and emotional exposure”. But I had questions. People seemed to be suggesting that if you just share your weaknesses and challenges then your problems go away. Was it really that simple? I could see neither data to back that up, nor examples of leaders who were doing it well. And even if being open and sharing is a decent solution in your personal life, I wondered if the same would hold true at work, where there is a completely different dynamic.

You’re probably a current or aspiring leader who sees the world around you changing, and you’re asking yourself, “How do I lead through this change?” You understand that connecting with people and being able to influence change is one of the most important aspects of leadership, yet you also understand that you need to demonstrate that you are highly capable of doing your job as a contributor to a team and organization. You know what it means to be vulnerable because you have experienced it, but like many leaders around the world, you’re probably wondering if you should be vulnerable at work.

I set out to discover how some of the world’s top leaders unlock the potential of others, create trust, and lead through change – and whether vulnerability is the same for leaders as it is for everyone else. It turns out, it’s not. While everyone knows what it feels like to be vulnerable, very few know how to lead with vulnerability.

When being vulnerable is not leading

On 20 August 1991, Hollis Harris, the then-CEO of Continental Airlines, told his 42,000 employees to “pray for the future of the company”. In a memo to employees he said, “we are in a battle here at Continental. We are at war with forces within the company and outside the company.” As Doug Parker, the chairman and former CEO of American Airlines told me, this is being vulnerable, but it’s not being a leader. The next day Hollis was fired.

If Hollis had been a junior employee working in accounting, those statements would have had minimal impact. Some employees may have taken notice, or maybe someone would have taken him out to lunch to ask him why he was having a bad day. He would have received some words of encouragement and support from his team leader, and life would have moved on. But when you’re a leader, the things you say have more impact.

Fleetwood Grobler is the president and CEO of Sasol Limited, a South African energy and chemical company with over 28,000 employees. He wasn’t in position for long before he was faced with Covid-19 and had to figure out what to do, and how to do it. As he told me: “I took over as CEO when the company was in very deep trouble with over $13 billion in debt. I was working in Lake Charles, Louisiana, finishing a project when I was told by the chairman in early October 2019 that the team wanted me to come back and be CEO by the end of October.”

Grobler was straight into the action. “They asked me to deliver the financial results, which I did for the first time in my life. This was at the end of 2019, and then a few months later in 2020 the pandemic happened. Our company suffered to the point where the banks almost came in and took over because our cash lines and credit flow was up and we were on the hook for $10 billion.” How did Grobler confront the company’s challenges? “In my first town hall, I told the company that I didn’t know the answers, but I knew we had a great team and that I could get us back on track. I told them that together we would find a way by rebuilding trust with our team and customers.”

Both Hollis and Grobler were vulnerable, but only one of them combined vulnerability with leadership.

Vulnerable leadership

I define a vulnerable leader as follows:

A vulnerable leader is a leader who intentionally opens themselves up to the potential of emotional harm while taking action (when possible) to create a positive outcome.

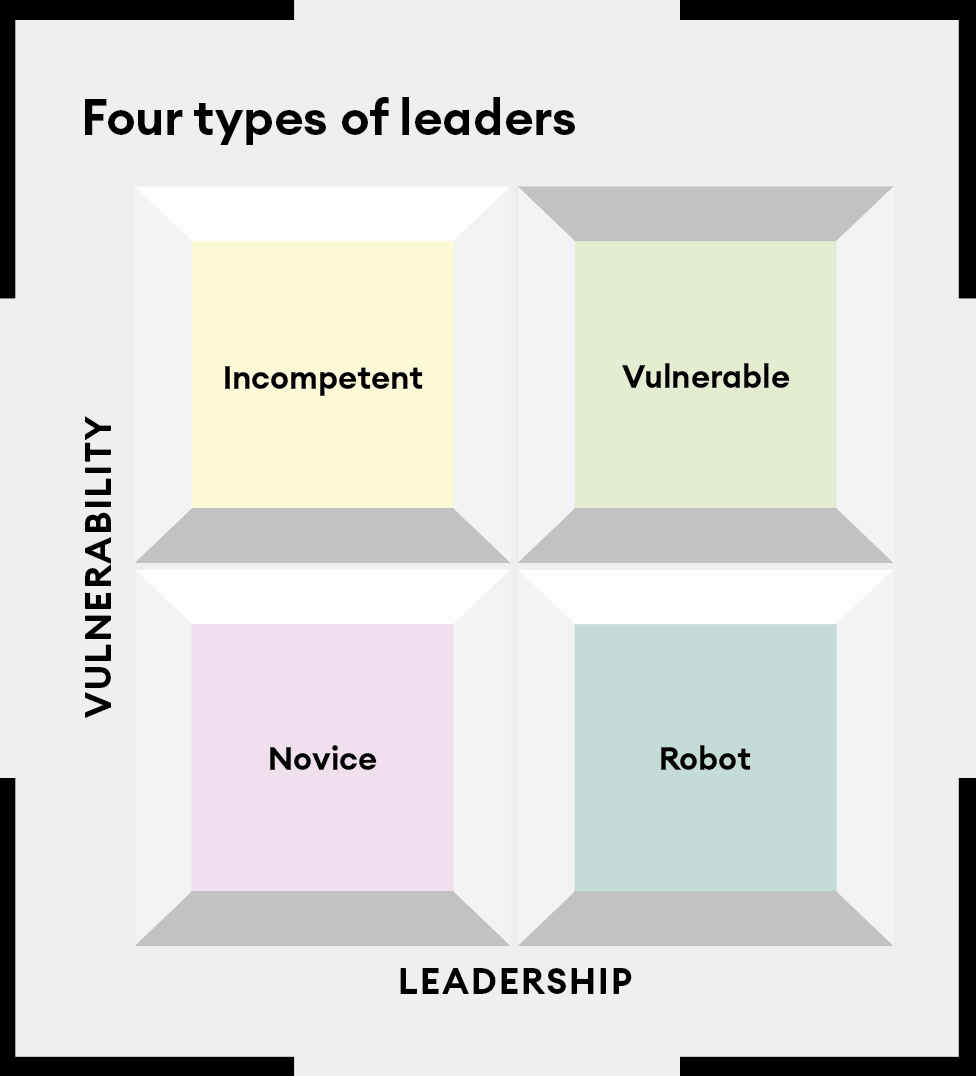

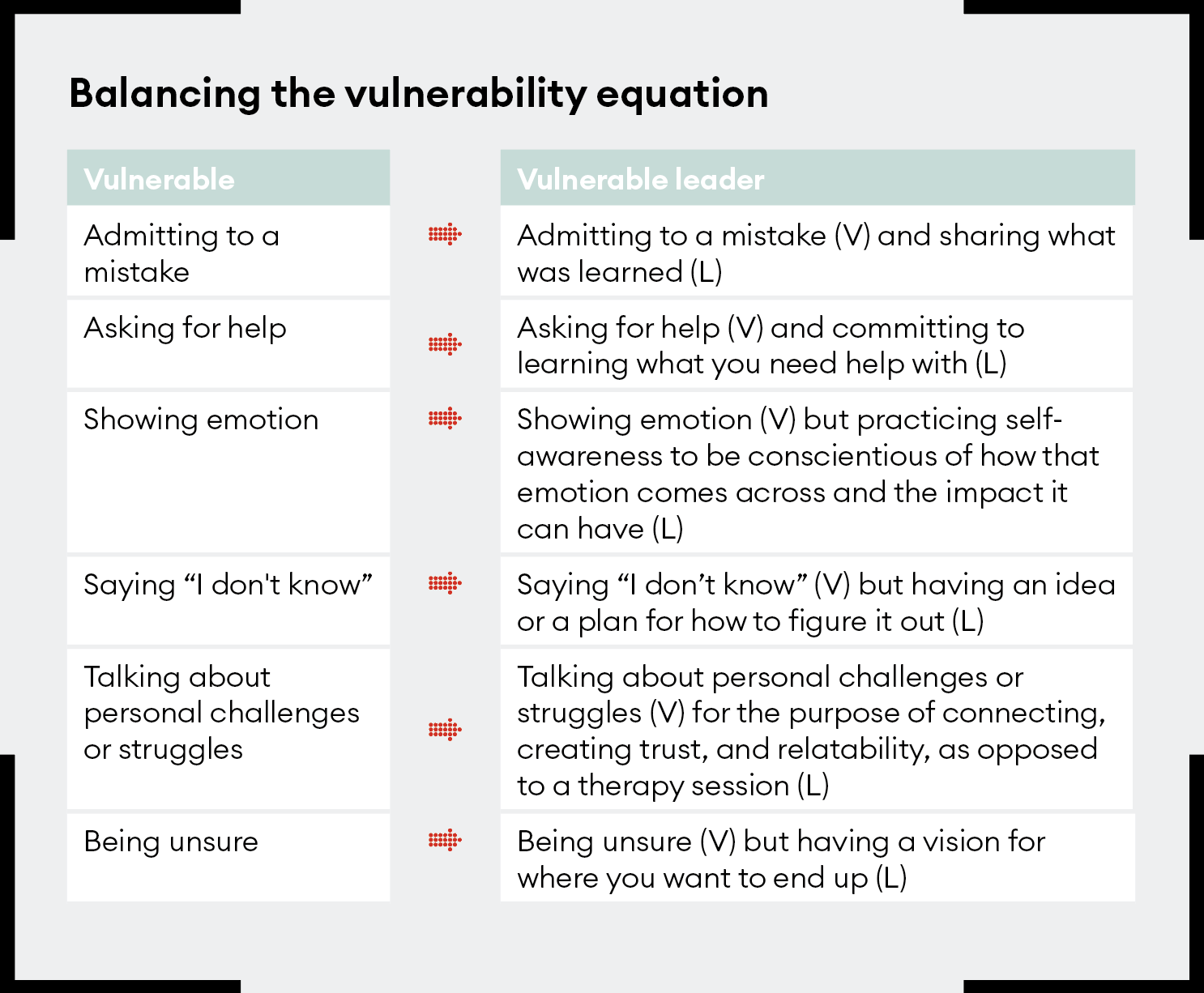

While vulnerability cripples some leaders, others are able to tap into it and use it as a superpower. Vulnerability alone makes leaders seem incompetent, whereas competence alone makes it hard for leaders to connect with their people. Leaders need both. It’s what I call the Vulnerable Leader Equation: V + L = VL.

For example, you admit to making a mistake at work and take action to fix it and review what you learned. You share a personal challenge or struggle at work to build trust, connection and get support. You ask for help and take action to get the necessary training required to get up to speed. The intended outcome is positive and you take action when you can. Vulnerability creates connection, and leadership is about being good at your job.

Larry Gies is the chief executive and founder of Madison Industries, one of the largest and most successful privately held companies in the world. “Teams don’t care what you think until they know that you care,” he told me. “You can be the most competent, but it will be meaningless to the teams if they don’t think you have their back. You can’t have their back if you are not vulnerable about the fact that you don’t have all the answers and you are not going to risk what you are building together because of your ego.

“On the other hand, if you are not competent, the team will lose their trust in you and you will not have the ability to be vulnerable.”

The four types of leaders

The novice is either new in their leadership journey, or someone who isn’t a leader yet. Therefore, they have not yet established their leadership or vulnerability. The path they take will determine what kind of a leader they become.

The robot is effective in leadership but struggles with vulnerability. These individuals can be thought of as more stereotypical leaders who got to where they are by focusing on competence over connection.

The incompetent leader is vulnerable yet struggles with the leadership side of the equation. Perhaps this leader was once quite competent but stopped learning and growing after becoming a leader. Another possibility is that this person became a leader simply by navigating office politics and bureaucracy. They are good at the human aspects of work, but should not be in a position where they are leading others.

The vulnerable leader combines the elements of vulnerability and leadership to achieve positive change and outcomes. These are the leaders who are both good at their jobs and can connect with their people on a human level.

Brad Jackson is the co-founder and chief executive of Slalom, a consulting firm with over 13,000 employees. He put this nicely. “Vulnerability by itself is not enough. It’s like hydrogen, which by itself can do some really great things. But when you combine it with leadership where there is a focus on outcome, reflection and trust, that’s when its true power becomes unleashed and it can exponentially improve your organization, it can change your life, and change the lives of hundreds, maybe even millions.”

The power of vulnerable leadership

Vulnerable leaders understand three truths:

- Leading from a place of connection and influence is more powerful than leading from a place of fear or compliance. Compliance checks things off a to-do list; connection and influence can change the world.

- The opposite of being vulnerable is not being invulnerable – it’s stagnation and eventual decline. You cannot learn and grow without vulnerability.

- The combination of vulnerability and leadership will transform you, your team, and your organization. It will unlock your true potential and the true potential of those around you.

Anyone has the power to combine leadership and vulnerability, including you. Whether you are a CEO or an entry-level employee, one of the best things you can do for yourself and your team is practicing the concept of vulnerable leadership.