Crowdfunding is not just a challenge to traditional lending practices. It represents the democratization of entrepreneurship.

It’s likely that you’ve heard of crowdfunding, whether through the media or through crowdfunding proposals popping up among your own networks. But what exactly is crowdfunding, and how is it different from traditional lending practices? In a nutshell, crowdfunding is a means of raising funding from “friends, family, and fools”, as it has sometimes been described. After explaining your idea to as many people as you can, you set up a website for donations and see how far you can get.

Crowdfunding can support commercial ventures or social enterprises. You can do it yourself or employ a crowdfunding agency, which may operate on an all-or nothing basis – either you raise the full amount you seek and they charge you a fee, or they return all donations and cancel their fee if they fail to raise the full amount.

You can offer subscribers rewards for different levels of contribution (see box, below). And it’s not just about raising money. The best crowdfunders also use the online community they create around their propositions to garner ideas and to test market and co-design goods and services. They also seem to have in common a strong set of values based on open access to funding, empowerment and making dreams come true.

In a recent interview, Renaud Laplanche, founder and chief executive of Lending Club, explained how his lending organization aims to transform banking through offering cheaper, peer-to-peer loans. “What Lending Club is actually doing is transforming the banking system,” Laplanche was quoted as saying. “We plan to develop all types of credit products [where] … the consumer loans market is in the trillions of dollars. The operating expense ratio for banks is between 5-7%. Ours is below 2% and trending lower every quarter. We have this 5% cost advantage that we can pass on to our customers, so it is really hard to see how banks could compete.”

When asked by the interviewer: “What is to stop JP Morgan Chase from cutting you out through doing all this themselves?” Laplanche replied: “There are three factors. There is the physical infrastructure – the branches. It would be really hard for JP Morgan Chase to close 5,000 branches overnight. Furthermore, Lending Club runs our entire operation on a nimble server farm in Nevada, a setup that has the same piece of code running on every single machine. Our platform was purpose-built. It does exactly what it was designed to do and nothing else. In contrast, the banks all run on disparate systems that came with the mergers of other banks, many built 25 years ago. Getting all these legacy systems to a place where they could run like ours, getting them to use technology that was developed in the past two years like we do, this is almost impossible.

“The third and most important aspect is really cultural. The kinds of people who come to work at Lending Club are those who say, ‘I want to transform the banking industry. I want to create something new and innovative.’ With a very different talent pool you end up with a very different outcome.”

When I started out on the interviews reported here, I thought this article would be a straightforward story of competition like Lending Club – crowdfunding as an alternative to a bank loan. What I discovered is that crowdfunders have common values and a lot of passion around community, idea generation, and access to, and democratization of, funding.

There are certainly places where crowdfunding and bank loans overlap. The banks seem keen enough to offer loans to high potential businesses and can even use crowdfunding intelligence to hedge their bets in the right direction. But crowdfunding has a different ethos and building a relationship with the crowd using your personal reputation currency is a big part of the difference.

WHAT DID CROWDFUNDING EVER DO FOR US?

The businesswoman

“Why do banks insist on seeing a five-year business forecast? Even with all the evidence in front of them, they couldn’t predict the crash of 2008.”

Madi Sharma is a serial entrepreneur and member of the European Economic Social Committee, where she campaigns for entrepreneurs and social enterprise. She has the energy of five people packed into one and was once criticized by a former employer for being “overenthusiastic”. She has no time for banks. “As a newly divorced, single parent in my twenties I couldn’t even get a bank account,” she tells Dialogue. Sharma had left an abusive marriage: “I had no experience, no skills, no money and no confidence. I started at my kitchen table with four samosas and ended up making 10,000 products a week, employing 35 long-term unemployed staff in two factories in regeneration areas. I was backed by my parents and a “white knight” mentor who never even looked at my business plan.”

Then, eight years after being named Asian Businesswoman of the Year, Sharma lost it all. She was allocated a business advisor through a government scheme, who turned out to be a fraudster and her company went bankrupt. Undeterred, she started again and now runs a network of eight companies scattered around the world. She uses the proceeds from these commercial entities to fund social enterprise and to teach entrepreneurs.

“Being excluded by a bank through not being allowed a bank account pushes people into the black economy, the cash economy,” she says. “Why do banks insist on seeing a five-year business forecast? Even with all the evidence in front of them, they couldn’t predict the crash of 2008. If I were the minister for banking, I’d make bank managers meet entrepreneurs, analyze the facts, consider their determination and back them based on gut feel, not business plans.”

The expert

Banks will continue to play a role, but only the good ones – for the rest, it’s already too late.”

Epi Ludvik Nekaj is founder and chief executive of Crowdsourcing Week, established in New York, US, in 2011. He has since moved the headquarters to Singapore. As described on the website, crowdsourcing is the practice of aligning many individuals to work towards a common goal. It employs collaboration for problem solving, funding, innovation and efficiency and is powered by new technologies, social media and web 2.0. Crowdsourcing Week was founded to support the transition towards a more open and collaborative economy.

It helps organizations power crowd-based solutions through providing services, conferences and online communities, also hosting two major conferences a year to inspire and connect people, as well as a series of one-day summits on two or three topics relevant to the crowd economy. Nekaj himself seems to live a life powered by web 2.0 – his extensive travel is made possible through renting fantastic, well-priced accommodation through Airbnb. To him, this is just one of the tangibles of a shared economy.

“The crowd economy is very powerful – it creates online communities, global citizenship and releases human potential,” he tells Dialogue. Social media allows us to put the best of ourselves forward to the world – I can rent great places on Airbnb because of my reputation currency. The future will be very different, it will be driven by stuff coming to you – we won’t have to go out searching any longer.

Like many entrepreneurs, Nekaj has bootstrapped Crowdsourcing Week, building it organically, but in October he intends to take his own medicine. ‘We will launch our own equity crowdfunding campaign to sell shares,” he says. “We want to harness the passion of those with similar beliefs – we’d like to get 100 or so investors. It’s not just about the money though – money comes last on the list of things to be gained. We want our investors and our crowd of stakeholders to help us to do things and get involved in our processes.

Power corrupts humans – harnessing the crowd allows for more distributed power and creates more opportunities. My contributors say ‘thank you for doing this’ not ‘what a great company you have created’. You become the conduit and outlet for ideas that people want to see happen.

“The internet is changing our world with the finance sector seeing some of the biggest effects. Hundreds of millions of people are becoming peer lenders and bankers – now everyone can invest, even with small amounts. Banks will continue to play a role, but only the good ones – for the rest, it’s already too late.”

The tech pioneer

“With banks you get money. We get amazing ideas from everywhere. We are looking at a gravity-based light that you literally bounce to generate light. In developing countries, it will replace kerosene lamps.”

Anastasia Emmanuel is UK director of technology and design with Indiegogo, the firstever crowdfunding platform launched in 2008. It specializes in raising funds through reward systems (see graphic, page 18), a method that it created, and not through equity funding. One of Indiegogo’s three founders, Danae Ringelmann, started out working for the bank JP Morgan, but left because she considered it broken. At the same time as working there, she was helping theatre producers to raise money on the side and she saw a successful play that investors failed to back because it didn’t have the right profile. It just didn’t make sense to her. Ringelmann met her other two co-founders at Berkeley and they bootstrapped the company for its first two years.

It now employs 120 people, all of whom own shares, has run 300,000 campaigns in 224 countries on an open platform (so that launches can be made in the fundraisers’ own countries) and works in four different languages. As many as 10,000 campaigns are active at any one time. Indiegogo takes a fee for every campaign, charging 4% against an industry average of 5%. However, it doesn’t take fees on donation-based or personal causes, such as fundraising for an operation. A campaign can take from four weeks to a year to prepare and an average of two to three months to launch. Campaigns can run for 60 days.

Emmanuel aspires to democratize access to funding and to get rid of the gatekeepers. “Crowdfunding has barely scratched the surface,” she says. “We get amazing ideas from everywhere and we offer genuine empowerment to bring aspirations to life. We are looking at a gravity-based light that you literally bounce to generate light – in developing countries, it will replace kerosene lamps with all their accompanying dangers.” Anastasia was hired over a glass of wine – the company looks for its employees to have face attributes (the acronym standing for fearlessness, authenticity, collaboration and empowerment).

“If you go to a bank you get money,” adds Emmanuel. “If you crowdfund you get advice, feedback, a way of gauging demand and engaging potential customers ahead of launching your product or service. You raise brand awareness and gain PR via social media – your reputation has to be visible to the crowd if you are to succeed. And of course, you get money as well. The crowd is motivated by getting unique access to a product or service ahead of time.”

The guru

“Whether you obtain funding depends upon how good your reputation is, and how clear your message.”

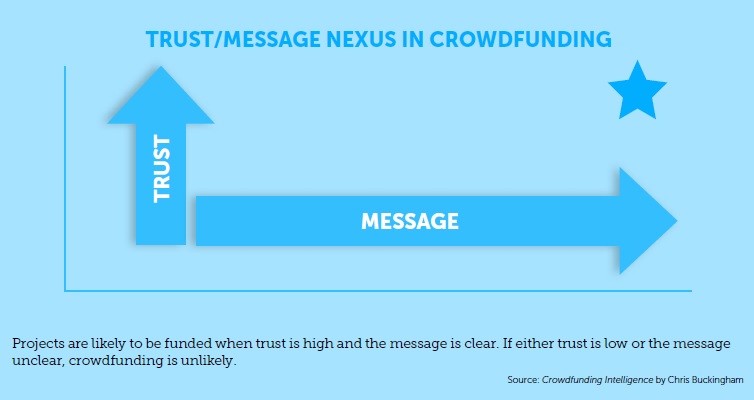

Chris Buckingham is a lecturer at the University of Winchester, researches at the University of Southampton and consults through an organization called minivation. He is author of Crowdfunding Intelligence, a guidebook for raising investment funds on the internet. “What differentiates crowdfunding is getting endorsement and consent from the crowd – it’s really important,” Buckingham explains. “It’s a unique world of pretailing, e-tailing and retailing.

At its heart it’s a social strategy and fundraisers are looking to gain the trust of the crowd. The creative industry generally finds raising loans from banks either too challenging, or the loan terms offered too stringent, so crowdfunding makes a lot of sense for them.”

Again, there is the same emphasis on what the crowd can offer in addition to finance. Do banks compete with crowdfunding? “There are algorithms that can identify winning ideas and allow banks to step in to offer loans to likely successes,” says Buckingham. “Entrepreneurs looking for equity investment are probably indifferent to where they raise capital – and banks might even offer them better interest rates.”

So it seems that banks are able to use crowdfunding intelligence as a way to step into the safe part of the market, where their returns are all but guaranteed. Other peer-lending organizations, such as Zopa, offer another form of lending; they make loans, dictate the rates and mask the identity of the borrower – the opposite ethos to crowdfunding.

Buckingham offers a simple method for potential crowdfunders to assess their likely chances of success. “Essentially, whether you obtain funding depends upon how good your reputation is (can the crowd trust you and your values?) and how clear your message is (does the crowd understand what you are trying to achieve?).” (See graphic, above.)

The mother

“You can’t change huge institutions such as banks overnight. That’s their weakness.”

Babou Olengha-Aaby founded Mums Mean Business (now The Next Billion) after the birth of her daughter, when she had time during sleepless nights to plan a business. She found a new sense of purpose and empowerment, feeling that, as a mum, she could achieve anything. “Banks only lend to those who can afford it,” she says. “You can’t change huge institutions such as banks overnight. That’s their weakness. As an industry, we have to pioneer the change we want to see, be a disruptive force that inspires a change of mindset from the banks in order to democratize the financial system.

“Crowdfunding invites everyone to participate by harnessing the power of the crowd and the shared economy for the greater good. Banks and venture capitalists can be part of this revolution if they choose. I would go so far as to say that they may soon run out of choice, as crowdfunding is set to overtake global venture capital funding by 2016, according to a recent report by Massolution.”

Olengha-Aaby believes there is a multiplier effect from investing in women; female-run businesses start with significantly less funding, grow slowly, and (if they survive the valley of death during the first two years) fail less often, offer higher returns and invest back into family and community: “Women own only 1% of the world’s property, but banks lend against assets, so more often than not the request is rejected, even though a bank is often women’s first choice for funding,” she says. “As a next step, many women use their own credit cards to fund their businesses. And finally, they seek to raise funds from friends and family.

“The good news is that crowdfunding is levelling the playing field for women, particularly in reward-based crowdfunding, where women dominate both as backers and as project-owners. Reward-based funding is also a great way for a female entrepreneur to validate her business model, gain traction and grow into equity funding. This method offers scale in a way that microfinance just doesn’t.”

ILLUSTRATION: NICK LOWNDES

An adapted version of this article appeared on the Dialogue Review website.