The ACE in your hand.

Our way of life has begun to be impacted by the advance of artificial intelligence (AI) in ways we could not have imagined a few years ago. The fast-moving evolution of our digital world, accelerated by the virus that has engulfed us in recent months, has raised numerous questions about our working lives. Many will take decades to fully answer. Given the pace of change, its intensity and the societal ruptures we face, it often feels like we don’t have time to get to grips with all the human issues this creates. Yet get to grips we must – and amid the chaos, there are definite rays of hope.

The acts of altruism, compassion and empathy (ACE) visible around the world since the pandemic hit are cause for optimism. They speak to humanity’s enduring emotional intelligence (EI) and, having (re)discovered the power of ACE during this crisis, we must now continue to harness its power, applying it in a sustainable way to help everyone. The application of EI and ACE concepts can be used to fuel a shared purpose and the achievement of organizational objectives.

In a world that has been reshaped at unprecedented speed, we can benefit from a fresh approach which recognizes that past behaviours are singularly unsuitable for a fundamentally different type of existence. What might we learn as a result of living through the chaos of Covid-19? Could we agitate for a new and different type of workplace – and seize a rare opportunity to reshape corporate culture?

Examining altruism

Altruism has the power to shape our lives. When I was a student in Japan, there was a day during the bitter Nagoya winter when I went into town to buy some books for my studies. As I emerged from the metro onto the freezing street, I noticed a woman in her early twenties collecting cash donations for famine relief in Ethiopia. By the sound of the coins in her collecting box, she wasn’t having much luck. I asked her how she was getting on. “Not too bad”, she said, in a way that confirmed she wasn’t doing at all well.

I suggested we move to the entrance of the metro. In service of boosting our collection potential and helping her out, I started to approach people with a cheery patter: “We’re collecting for Ethiopia, the starving families, could you spare any change?” In no time, we had people fumbling for cash.

The collection tin got heavier.

My newfound friend and I were delighted. But then we were stopped by a middle-aged lady. “Why should I give you money for Ethiopia?” she demanded. Because it will help the people over there to survive, I told her. It triggered a rant: “But what could the people over there ever do for us here in Japan? Ethiopia is too far away to be of importance to us. I think this is all a stupid idea. So no, I will not give you any money.”

This all happened nearly 40 years ago, but the impact of the experience stuck with me. I realized that not everyone shares the same perspective about the value in doing something simply because it helps someone else and makes you feel good. Today, we know altruistic acts are not only good for the beneficiary of our help: we have learned that the act of helping someone else without an obvious ‘payback’ is actually good for the person performing the act of selflessness. At a neurological level, it bathes one’s brain in feel-good chemicals.

Why, then, don’t we act altruistically more often? Did we really need to wait for a pandemic to harness the power of altruism?

Sympathy, altruism, compassion and empathy

In a recent article in The New Statesman (April 2020), the English philosopher John Gray describes the pandemic as a “turning point in history”, in part because of the wave of generosity to others that has been unleashed. He warns, though, that such altruism is a precious commodity, which should not be squandered. An estimated million members of the British public volunteered to help the National Health Service during the crisis: but, writes Gray, “it would be unwise to rely on human sympathy alone to get us through. Kindness to strangers is so precious that is must be rationed.”

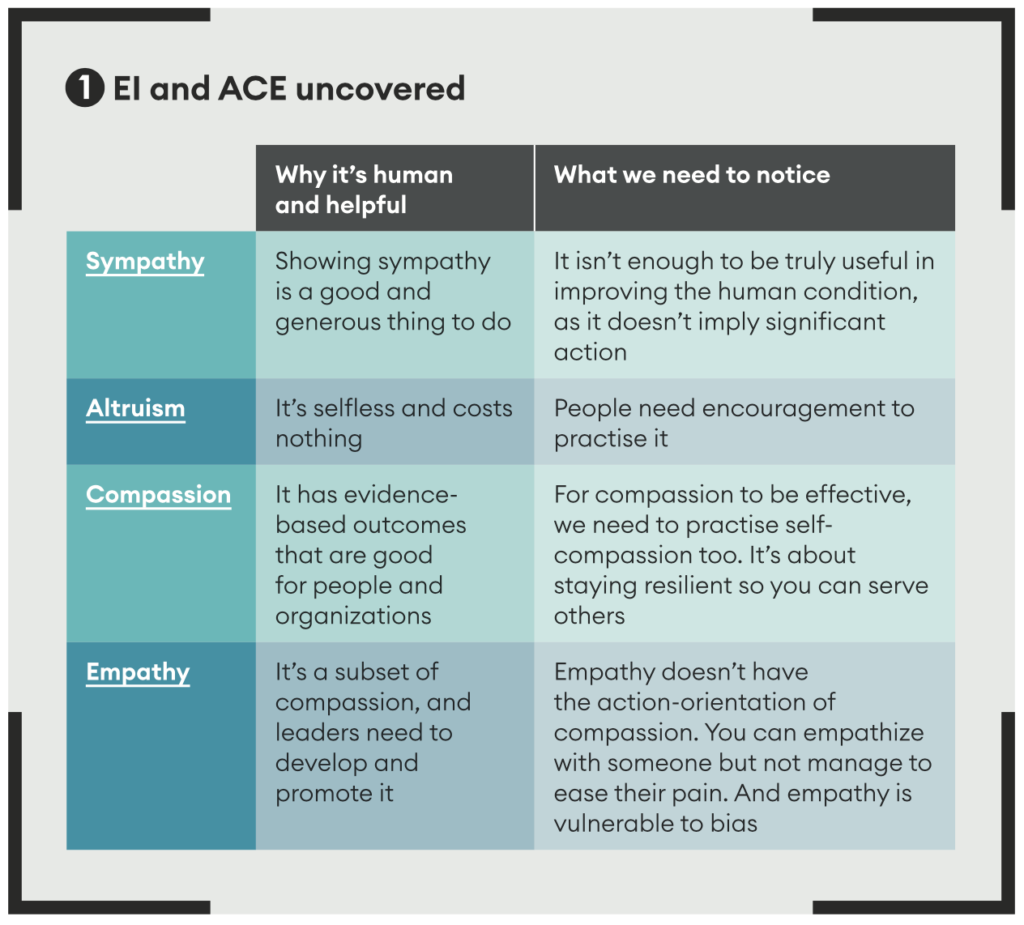

Gray raises an interesting point, but he runs the risk of conflating sympathy with altruism. It is a common error in thinking about compassion and empathy as well. Sympathy and altruism are not the same thing (see Figure 1). Here’s how we might think of these concepts:

Compassion and sustainability

“Compassion is essential for a sustainable future, both socially and environmentally,” wrote academic and researcher Anne Tsui in her paper, ‘On Compassion in Scholarship: Why should we care?’ (The Academy of Management Review, March 2013). This is a core idea, which we should embrace: ACE’s elements are not simply good qualities, ‘nice to have’; they are essential for our collective, sustainable, digital future.

A worker at an international relief agency once told me: “We’re way too busy being compassionate to people who need us, to be compassionate towards the people we work with – our colleagues.” The same person admitted that the quality of service humanitarians provide to those in need would likely improve if aid workers took the time to be more compassionate to each other.

This makes the point that being compassionate is not about being saintly, good, or even ‘nice’. It is far more demanding: it’s about learning to be a better listener so that you can truly notice when someone needs your help; making sure you exercise self-compassion, facing up to things in the past that you’re not proud of and forgiving yourself; and ensuring you prioritize your own resilience. The good news is these things can be learned and developed.

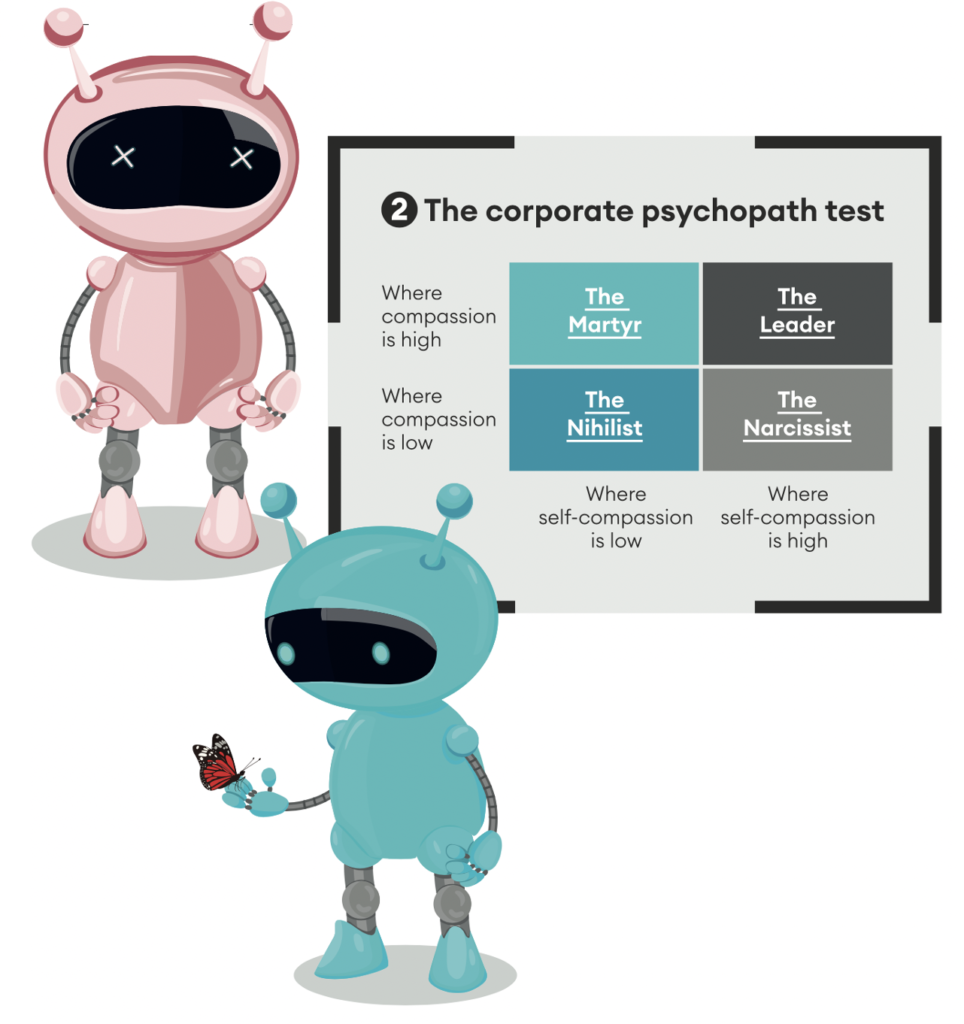

Self-compassion and altruism: identifying corporate psychopaths

The grid (Figure 2) opposite shows how the leadership displayed by leaders is shaped by the relative emphasis on compassion (towards others) and self-compassion (compassion directed at you, as an individual). In the top right quadrant is the Leader: those who display high levels of both compassion and self-compassion. Where people do not pay attention to their own need for self-compassion and spend their time and energy worrying about others, we find the Martyr.

The Nihilist of the bottom left-hand quadrant occupies a bleak place: lacking in self-compassion and singularly disinterested in the welfare, or physical or mental wellbeing, of others.

In the final quadrant, where there is a lack of care or even interest in others, the preoccupation in oneself can mean that self-compassion morphs into something else entirely. This is where, in extreme cases, we find the Narcissist.

I am certain we’ve all encountered this person in our careers – possibly more than once. Such individuals damage both people and organizations, which is why it’s critical to identify a dangerous lack of altruism in our leaders as early as possible. There are those, too, who turn out not only to be narcissists but full-on corporate psychopaths: in other words, people who are incapable of altruism.

Organizations of the future will need ACE leaders more than ever – not only because of the benefits to the people they lead, but because business success demands it. Post-Covid, consumers will remember and avoid any companies that were rapacious and unfeeling during the pandemic. They will follow instead those firms who managed to combine the best of EI and AI, delivering innovative digital services with a gentle, human touch. The number of posts and messages on LinkedIn which referenced putting people first (“caring for employees”, “honouring healthcare workers”, “supporting local communities”, etc) has soared during the course of the pandemic: they are the ones that are attracting the most attention. There is little doubt that empathic employer branding is resonating with people.

Artificial intelligence to the rescue?

While we accept that the world is facing a monstrous challenge, this time things are different: unlike the Spanish Flu, the Great Depression, or even the financial crash of 2007-08, we have at our disposal an array of digital tools and support systems that make our lives more liveable. In many parts of our lives, their adoption has undoubtedly been accelerated by the pandemic.

Will we have a price to pay for this acceleration in terms of sensitivity in human interaction? Will we start to experience ‘de-humanization’ as a result of the steep increase in our use of virtual communication platforms, or the deployment of other digital tools? The advance of the chatbots and other AI applications, together with the surge in online meetings, has the potential to create ‘emotional distance’ between us and our colleagues or customers. That could compromise our ability to empathize and to truly ‘connect’ with others.

I am inclined to take an optimistic view of the outlook. While AI and its associated tools might adversely affect EI, the potential for us to use AI for good – especially in conjunction with altruism, compassion and empathy – holds rich possibilities. In the UK, the Run for Heroes challenge asked supporters to run five kilometres, donate five pounds to charities supporting healthcare workers, and suggest five other people to carry out the challenge. The call to action was pushed out to great effect on Instagram. Another great example of EI and AI coming together was the star-studded virtual concert, ‘One World: Together at Home’, orchestrated by Lady Gaga in April 2020. And amongst the many direct countermeasures taken against Covid-19, some of the most effective have been driven by mobile phone technology, as in South Korea, enabling timely contact tracing and regular updates. Technology and ACE thrive when deployed together.

A fundamental question: beyond AI

Perhaps the most fundamental question prompted by Covid-19 – a question which cannot be handled by AI – is this: how altruistic are you prepared to be? Are you willing to compromise or change your behaviour in the service of others? And if so, to what extent?

Altruism may turn out to be the defining EI quality of our time. Complemented by compassion and empathy, and imaginatively paired with and powered by AI, it is exactly what the world needs right now.

– Michael Jenkins is chief executive of Expert Humans in Singapore. He was previously chief executive of the Human Capital Leadership Institute, and of Roffey Park Institute.