Fear can paralyse – or, targeted on valid concerns, can stimulate effective action and innovation.

On 4 March 1933, US President Franklin Roosevelt uttered the famous words: “Let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself – nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.” The quote is usually abbreviated to the italicized portion, but the full sentence conveys the psychologically accurate notion that fear was inhibiting the very actions needed to solve the challenging problems facing the nation. It points to the tragedy of letting fear get the better of us, and getting bogged down by what I call ‘unproductive fear’.

Modern psychological research backs up Roosevelt’s claim. Fear can indeed paralyze, inhibiting the very behaviours that are vital to progress (see J Kish-Gephart et al, including the current author, ‘Silenced by fear: The nature, sources, and consequences of fear at work’, in Research in Organizational Behavior vol 29, 2009). I have been studying the problematic effects of fear in workplace hierarchies for more than 20 years. My earliest research showed that interpersonal fear in hospitals inhibited the error reporting that is so essential for patient safety and quality improvement – and, as I explore in my latest book, The Fearless Organization, numerous subsequent studies have found empirical support for the effects of ‘psychological safety’ – a state of low interpersonal fear – on learning and performance in teams across industries and sectors.

The explanation for these robust findings is that most work today is knowledge work, and most workers face considerable uncertainty and interdependence that must be navigated collaboratively to succeed. When people are afraid to speak up with questions, observations, concerns and mistakes, problems go unsolved, innovation is limited, and performance suffers.

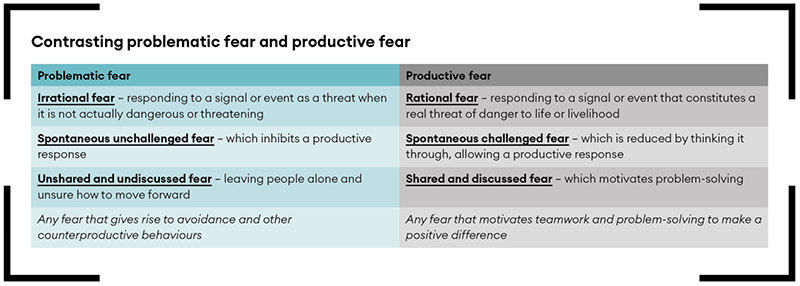

Recent attention paid in the management press to the importance of creating psychologically safe workplaces is gratifying. However, confusion about workplace fear remains. Instinctively, people understand that erasing all fear at work is unrealistic – and maybe even counterproductive. They’re right. The key for today’s leaders is to recognize the difference between ‘problematic fear’ and ‘productive fear’.

Fear itself

Let’s start with the basics. What is fear? And why does it play such a central role in human existence? Psychologists, such as Nico Frijda and Batja Mesquita, define fear as an emotion that manifests as an urge to separate oneself from aversive events – that is, from unpleasant stimuli or situations. Fear is thus a spontaneous response to a perceived threat. We don’t consciously decide to become afraid, but once in its grip, our thoughts and behaviour are powerfully shaped by it. Although people can experience what is called a ‘generalized anxiety’ without a specific trigger, fear, in contrast, is an emotion in reaction to a target. That target activates an ‘action tendency’: to withdraw or distance oneself from the threat. In short, fear activates self-protection, a spontaneous – and at times healthy – human response to threat.

Evolutionary psychologists note that our brains are endowed with ‘prepared fears’: fears that are easily activated because of cognitive wiring from our evolutionary history. Yet some of these prepared fears no longer serve us (N Frijda, The Emotions, 1986). For early humans, ostracism was a truly life-threatening condition: if the leader didn’t like what you did or said, you risked being kicked out of the tribe, resulting in starvation or exposure. But today, the prepared fear of being ostracized leaves us vulnerable to being ineffective at work.

Interpersonal fear makes us hold back tentative ideas, questions and concerns. In a knowledge economy, where ingenuity and problem-solving are more valuable than conforming and keeping one’s head down, this instinctive self-protection can leave us worse off than we would be if we simply took a deep breath and spoke up. Our observations or ideas just might be the crucial data that shift the course of a risky project for the better, but our spontaneous emotional wiring has not re-adjusted for the modern world.

Of course, we face no shortage of targets to activate fear. A pandemic, violent behaviour, dangerous weapons and even an economic recession are all worthy targets. But fear is also activated by targets which, strictly speaking, are not dangerous to our health or livelihood. Much workplace fear can be categorized as irrational, in that our lives are not at risk, yet our physiological response mimics that to life-threatening stimuli. Fear of what others might think of your idea is especially problematic for knowledge-intensive work.

This points us toward the essential distinction between productive and problematic fear. When we protect ourselves from real threats, we live to see another day. When we protect ourselves from interpersonal threats, we are at risk of making the situation worse. Worried about what the boss might think, we hold back on sharing some out-of-the-box new idea, thereby failing to contribute to the project, thereby limiting innovation, and so forth. Meanwhile, a failure to speak up may even make the boss think less of us, because of our lack of contribution to the discussion. The widely held belief that “no one ever got fired for silence” is obsolete in any organization that depends on continuous improvement, effective risk management, and innovation for its success.

Problematic fear versus productive fear