Intensifying scrutiny and intervention demand a new leadership model for regulated industries, say Beth Ahlering and Gary Storer.

When Mark Zuckerberg was questioned by US Congress in April 2018 about alleged misconduct at Facebook, he served as a high-profile example of a new phenomenon impacting global leaders. Since the 2008-10 financial crash, there has been increased social, political and regulatory pressure on business. Zuckerberg admitted: “We didn’t take a broad enough view of our responsibilities, and that was a big mistake. It was my mistake, and I’m sorry. I started Facebook, I run it, and I’m responsible for what happens here.”

Across the world, leaders are held to account for past decisions or for actions in which they may have had little or no direct involvement, such as systems failures providing customers with misleading statements, sales teams selling the wrong products, or a bullying culture in the workplace. Historically, senior managers were held to account for breaking the law, negligence or major financial losses. Today, regulators hold them accountable for the impact of day-to-day decisions on customers and markets.

Increasing scrutiny

While all business is subject to regulation and legal obligations, sector-specific regulators have a mandate to protect citizens and consumers where misconduct can leave them suffering significant harm. Financial services, telecommunications, pharmaceuticals, legal services, education, the charity sector, care providers, energy suppliers and the public sector have their own regulators and ombudsman services. There are also pan-sector regulators, such as the new data security bodies. All of these regulators are increasingly interventionist, concerned with setting conduct standards and dealing with misconduct rather than, as formerly, solely with strategic issues such as pricing or competition.

In 2017, Gary Storer spent more than 100 hours interviewing leaders from these sectors about the impact of the heightened accountability they faced, exploring whether there are particular skills or ways of thinking that differentiate successful leaders in regulated sectors. Many interviewees highlighted the personal challenges they had encountered. One leader had to present a major remediation plan to the UK Financial Conduct Authority. Realizing that he was personally accountable for its implementation and that the immediate future of the business was at stake, he said: “I felt I was carrying not just my own accountability and career as we drew up the remediation plan, but also the financial well-being of my company, the jobs of many of our staff and the returns of our shareholders… if we had been fined I felt I would have let everyone down.” Being subject to the intervention of external regulators means facing a significant layer of additional demands not faced by leaders in non-regulated sectors.

Another commented that he felt continuously accountable and responsible for what happens to customers, much more acutely than when he led a non-regulated technology business. One leader talked about the pressure of presenting to non-executive directors who were increasingly challenging, conscious of their own duties to question and probe. He described presenting the business strategy to regulators who approached issues solely from the perspective of protecting customers, not understanding the organizational complexities or the market and employee consequences of their comments. They underestimated, for instance, the cost and time needed to improve how complaints were handled and to strengthen the customer culture, setting an unrealistic six month deadline for major improvements.

A new model for regulated leadership

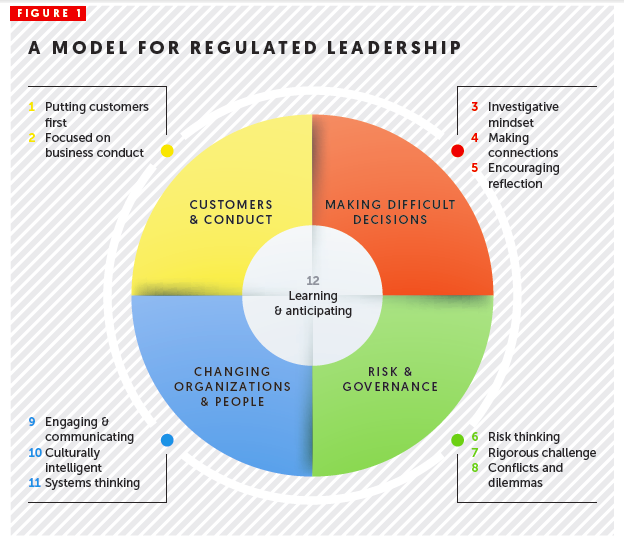

Twelve characteristics, skills and areas of focus emerged from our research as vital for leaders in regulated sectors. They can be gathered into five main clusters (Fig. 1), and they differentiate the more successful and experienced regulated leaders from their competitors.

1. Putting customers first

Genuinely putting customers at the heart of everything that happens and all decisions that are made, and feeling accountable for a moral ‘duty of care’ towards customers.

2. Focused on business conduct

Prioritizing change initiatives, investment and activity which will maintain or raise standards of conduct and, therefore, safeguard or enhance outcomes for customers.

3. Risk thinking

Valuing the importance of understanding risks and managing them. Seeing risk as a fundamental domain of management and leadership, not just a technical hygiene issue.

4. Engaging and communicating

Recognizing that change, performance and delivery to customers is dependent on engaging people and two-way communication, rather than relying on status, top-down cascade or a forceful personality.

5. Conflicts and dilemmas

Understanding that decision-making and action in regulated businesses are dominated by apparent conflicts and dilemmas which need to be explored, managed and resolved.

6. Culturally intelligent

Devoting most personal time and energy on people and culture as the core enablers of business success rather than targets, operations, process or technology; understanding the complexity and nuance of changing people and culture.

7. Investigative mindset

Diving into the detail of information, plans and proposals when necessary and spending time exploring the business to get to know, first hand, what goes on, the people, products and services, and how customers are treated.

8. Making connections

Drawing on previous experience and knowledge, considering different viewpoints and arguments to see the ‘full picture’, and drawing accurate conclusions from patterns and trends.

9. Rigorous challenge

Not accepting glib answers or over-optimistic claims about what can be achieved, and always questioning their own beliefs and views to ensure they are sound.

10. Encouraging reflection

Making time for thinking and reflection, and expecting others to do the same before acting; ensuring the pace of decision-making and change is not dangerously fast, or that management is too stretched.

11. Systems thinking

Managing effective oversight of the alignment of the many parts of the organizational system such as people, policy, products, processes, technology and controls.

12. Learning and anticipating

Focusing everyone on learning from changes and experience, and increasing their knowledge and capability. Anticipating the impact of initiatives and change through scenario-thinking, modelling and stress-testing.

Skills to dial up…

“It’s like a graphic equalizer on the stereo system,” said one bank’s managing director. “You have to turn up some things you do and turn down others.” It’s not that there are substantially different leadership skills needed for regulated sectors, but rather that some need to be emphasized, while others can create instability. For example, to maintain a balance between managing risk while not becoming overly bureaucratic, leaders need a deep understanding of their business operations and the risks on the front line. Leaders in regulated businesses need more technical and product understanding, and the ability to challenge their specialists. These leaders pay attention to detail, not simplified recommendations. They understand that in the regulated world, decisions are complex and situations are often messy or chaotic. Regulators expect these leaders to understand the small print. This can be disconcerting to reporting managers and risk specialists who are challenged on their analysis, explanation and assumptions.

Perhaps one of the most interesting characteristics of successful regulated leaders is a heightened capacity for ‘learning and anticipation’. They explicitly demand that they themselves, and their managers and businesses, learn from failures or mistakes. They ask for investigations and reviews when things go wrong, and they are personally reflective. As well as being adept at learning from experience, successful regulated leaders also seem skilled at anticipating future outcomes from market changes, customer behaviour and organizational change initiatives. Specifically, they use value modelling, stress-testing and forecasting against worst-case scenarios when making decisions.

…and to dial down

Some leadership skills need to be dialed down. For example, given the focus on cultural sensitivity, engagement and information gathering, leaders who are predominantly charismatic, forceful, vision-led communicators are less likely to be successful in regulated environments. This leadership style can suppress the escalation of risks or compliance issues, as we saw in the financial services crisis.

Similarly, leaders who are focused on driving organizational transformation at pace may not encourage sufficient reflection, stability, investigation, risk modelling or discussion to perform effectively. Leaders who over-prioritize commercial growth and profitability above their duty of care for customers are likely to fail in regulated environments, often more catastrophically than in other sectors.

Leaders who move from successful careers in non-regulated sectors frequently struggle, finding their entrepreneurial instincts reined in. They can become frustrated by what they see as unnecessary control. They need to quickly develop their ability to judge which controls are indeed too burdensome, and which are needed to prevent risks or demonstrate compliance. Many such leaders can appear dismissive of the concerns of regulators, who then place their organizations on higher monitoring.

Leaders need to learn the rules of their new game quickly, and judge carefully when they need to be disruptive, without being dangerous. These incomers must build a relationship with their regulators, which is an art in itself given their often different styles.

A case study in change

HomeServe, a UK retail insurance intermediary, lost many customers because of mis-selling, poor systems, controls and risk management over a period of six years. It suffered severe reputational damage, as well as major regulatory intervention and a £34m fine in 2014 for mis-selling. A new executive team was put in place, alongside new managers, and chief executive Greg Reed reorientated the business to put its customers first, instead of profitability or sales targets.

“We had to rescue the business in the short term, but we realized in year two that the changes were being driven through by us as senior leaders, [and] actually we weren’t changing the thinking of our people or how they dealt with customers,” Reed said. “The shadow of the previous leadership team was so heavy that even when they were no longer around, people kept old behavior patterns.

“We had to change the minds and behavior of our people. We communicated and communicated, changed compensation packages, instituted daily ‘customer first’ meetings, re-trained people and, inevitably, many found this wasn’t the organization for them and moved on.

“I think it took me three years of constantly asking people for their views and opinions until they really trusted that I meant it, and they stopped telling me what they thought I wanted to hear.”

Investing in leaders

Our regulated leadership model shows that there is a premium on different skills and characteristics for leaders in these sectors. Too often, the pressure to reduce prices to consumers means that spending on leadership development is slashed, which is a false economy. In fact, these leaders should be developed differently from the approaches classically employed by the major business schools, as we will explore in a future Dialogue article.

No executive wants to find themselves in the spotlight and on the defensive like Zuckerberg before Congress, but it is an ever-present possibility for leaders in regulated sectors. Knowing which behaviors to dial up is critical to avoiding that fate.

— Gary Storer is founder and managing director of Enterprise Learning. Beth Ahlering is managing director and professional practice lead at Duke Corporate Education. An adapted version of this article appeared on the Dialogue Review website.