Answering these six questions for yourself every day can help you reflect and develop as a leader and a person.

Just like some people exercise or practice a hobby religiously, I have a daily tradition: every day, I get the same phone call. The voice on the other end asks me a series of questions: did I do my best to be happy that day? Set goals? Make progress on those goals? I came up with these and some 40 other questions myself, a brief self-test on my life’s main priorities. My caller offers no judgment, just listens politely and perhaps offers a few general words of encouragement before hanging up.

This process, which I call the Daily Questions, keeps me focused on becoming a happier, healthier person. It provides discipline I sorely need in my busy working life as an executive coach, teacher and speaker, which involves travelling 180 days out of the year to countries all over the globe.

As I argue in my latest book, authored with Mark Reiter, Triggers: Creating Behavior that Lasts – Becoming the Person You Want to Be, in every waking hour we are being triggered by people, events, and circumstances that have the potential to change us. The Daily Questions provide an antidote to that chaos.

The process appears to be almost robotically simple: in effect, I’m taking a test I wrote, to which I already know the answers. But after years of dedication to this process, I now hold the counterintuitive belief that the Daily Questions are in fact a very tough test, one of the hardest we’ll ever take.

To understand why, you first need to grasp a fundamental truth about human behaviour. Changing it is hard. Very hard. I like to say that behavioural change is just about the hardest thing for sentient human beings to accomplish.

As an object lesson, think about a change you’d like to make. Perhaps you want to be more patient, or a better listener, for example. Now, think about how long you’ve been trying to make that change. I’m going to hazard a couple of bets. My first wager is that the change is something important to you – otherwise, why would you bother to change it? My second punt is that you’ve been trying for a long time – that you’d probably measure that time in months or years rather than days or weeks.

At this point you might be feeling a twinge – maybe even a stab – of regret, thinking about that talent you never used, that weight you never lost, or that friend you didn’t have time to listen to. The upshot is this: our behaviours matter. Perhaps they matter more than our achievements. We don’t live with our promotions and university degrees every day, but we do live with our choice to be better people.

The Daily Questions are so hard because, if we answer them honestly, they force us to face those choices. Because we wrote the questions ourselves, we can’t blame some outside entity for imposing goals that don’t really matter to us. Because we are the only ones responsible for coming up with the right answers, we can’t say we didn’t know what we were supposed to do.

The power of active questions

What you want to accomplish by asking these questions is not particularly important to me. That is up to you! The way you phrase these questions is important. I have found that active questions are far more helpful than passive ones.

I learned about the power of active questions from my daughter Dr Kelly Goldsmith, who has a PhD from Yale University in behavioural marketing, and teaches at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management.

Kelly and I are both fascinated with employee engagement, the term used in management circles to describe a state of active involvement in work that you might liken to an athlete being ‘in the zone’. Kelly’s key insight was this: if companies want their employees to be engaged, they should avoid handing out the typical surveys that ask workers what their bosses and managers can do to improve. These surveys aren’t bad. They provide companies with many valuable suggestions. But they are diagnostic, not curative. They do nothing to put employees in an engaged mindset.

Only the employees themselves can do that – and a good way to remind them is to ask active questions about their working lives. For example, instead of asking the passive, “Were you happy today?” (a question that invariably produces a laundry list of complaints), Kelly suggested asking an active question: “Did you do your best to be happy today?” The ball is now in the employee’s court. They have to evaluate and take responsibility for their own actions.

This logic dovetailed with my own Daily Questions process. Feeling that my personal questions were static and uninspiring, I tweaked several of them to reflect Kelly’s active formulation. For example, I changed a few of my questions as follows:

From “did I set clear goals” to “did I do my best to set clear goals?”

From “how happy was I?” to “did I do my best to be happy?”

From “did I avoid trying to prove I was right when it wasn’t worth it?” to “did I do my best to try to avoid proving I was right when it wasn’t worth it?”

Suddenly, I wasn’t being asked how well I performed, but rather how much I tried. The distinction is meaningful because in my original version, if I wasn’t happy, or I overate during the day, I could always blame it on some factor outside of myself. I could tell myself I wasn’t happy because the airline kept me on the tarmac for three hours (the airline was responsible for my happiness). Or I overate because a client took me to his favourite barbecue joint where the food was abundant, calorific and irresistible (my client – or was it the restaurant? – was responsible for controlling my appetite).

Adding the words “did I do my best” injected the element of personal ownership, of responsibility into my Q&A process. After a few weeks using this checklist, I noticed an unintended consequence. Active questions themselves didn’t merely elicit an answer. They created a different level of engagement with my goals.

To see if I was trending positively – actually making progress – I had to measure on a relative scale, comparing the most recent day’s effort with previous days. I chose to grade myself on a one-to-ten scale, with ten being the best score. If I scored low on “did I do my best to be happy?” I had only myself to blame. We may not hit our goals every time, but there’s no excuse for not trying. Anyone can try.

The survey

At the moment, I have 43 daily questions. There is no correct number. It’s a personal choice, a function of how many issues you want to work on. Some of my coaching clients have only three or four questions. My list is 43 questions deep because I need a lot of help (obviously), but also because I’ve been doing this a long time, and I’ve had years to deal with some of the broad interpersonal issues that seem like obvious targets for people just starting out.

If you’re not sure what to start with, I recommend the questions I use in my online survey (see below). These questions cover the basic tenets of employee engagement, but they work well in other areas of life as well.

They are:

1 Did I do my best to set clear goals today?

2 Did I do my best to make progress towards my goals today?

3 Did I do my best to find meaning today?

4 Did I do my best to be happy today?

5 Did I do my best to build positive relationships today?

6 Did I do my best to be engaged today?

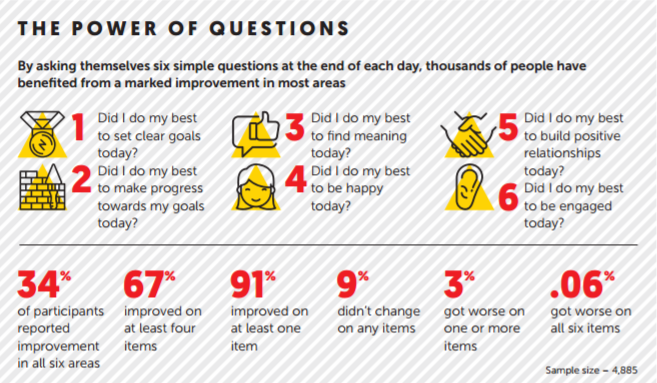

If you take the online test, we follow up after ten days and essentially ask, “How’d you do? Did you improve?” So far 4,885 people have participated from all over the world. The results have been overwhelmingly positive (see graphic, below).

Given people’s demonstrable reluctance to change at all, this study shows that active self-questioning can trigger a new way of interacting with our world. Active questions reveal where we are trying and where we are giving up. In doing so, they sharpen our sense of what we can actually change. We gain a sense of control and responsibility instead of victimhood.

— Dr Marshall Goldsmith is a multiple award-winning business educator and coach. If you would like to participate in his survey, email him at marshall@marshallgoldsmith.com.

An adapted version of this article appeared on the Dialogue Review website.