Finding your performance ‘sweet spot’ is difficult, but neuroscience and complexity theory can help, explains Bill Duane.

The span of business transformation is broad and increasing exponentially. In our turbulent world, success requires reacting quickly to changing dynamics and working differently. But there’s one problem: our nervous system responds to complexity and the unknown with a primal ‘fight or flight’ tool set which, in the modern world, can cause us to make things worse.

Leading in complexity calls for a level head, a willingness to let go of what previously made you successful, and a firm set of values that provide an anchor. Happily, these behaviors are eminently trainable. My experience working on these issues during 12 years at Google and a decade consulting is that the disciplines of complexity theory and neuroscience help point out the path ahead.

Cause and effect ain’t what it used to be

One of the signature features of the complexity we face today is the relationship between cause and effect. The Cynefin framework, developed by Dave Snowden of Cognitive Edge, divides systems into four ‘domains’:

- Systems are simple when cause and effect are readily observable

- Systems are complicated when causality is there, but expert analysis is required

- Systems are complex when causality is an emergent quality of what’s happening now

- Systems are chaotic when cause and effect are nowhere to be found.

To make things interesting, systems slip in and out of these conditions, sometimes quickly; and the sheer level of change around us, in technology, markets, political institutions and culture, means that the relationship between cause and effect changes more often than it used to. This is the world that the US Army describes as VUCA: volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous. Many types of work that were simple or complicated are now complex and sometimes chaotic.

Unfortunately, established ways of managing systems assume a steady state of causality, where we can measure the past to predict the future and make adjustments to optimize results. But managing a complex system as if it were a simple or complicated system will fail. Instead, our approach has to be nimble and constantly recreated, as we assess emerging causality, rally around it and then let it go for the next round. Managing complexity involves trying out many new ideas and quickly culling the ones that don’t work, constantly moving on to what’s next. That is easier said than done, however: we can all become deeply attached to our preferred ways of doing things. They become our professional identities – and when you start messing with issues of identity, work gets stressful.

Neuroscience and stress: your job is not a bear attack

Stress is the nervous system’s reaction to perceived challenges, including rapid environmental change. When an animal encounters stimuli that may be a threat, the sympathetic nervous system is activated, producing the fight-or-flight response. The same system has survived in humans: we have a nervous system optimized for bear attacks. The eyes widen, the heart beats faster, energy is made available for action and the senses sharpen.

There are a lot of benefits from this, including enhanced physical and cognitive performance, strong motivation, and focus. In moderate amounts, this is the feeling of being on your toes, ready for what comes next and excited about the challenge ahead.

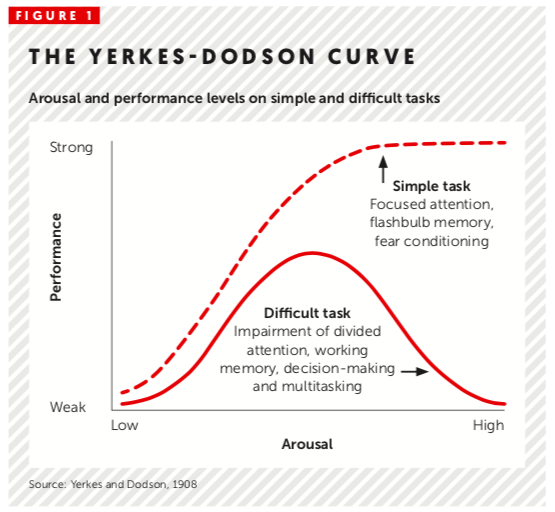

However, the effects can turn negative in two ways. First, the stress response is best suited to simple tasks, like escaping physical danger. Our performance on complex tasks can be improved by moderate stress, but only up to a point (see Figure 1), beyond which performance suffers: focus becomes tunnel vision, cognitive performance becomes reflexive panic, physical sensations of anxiety become inhibiting, and our social information-processing tilts towards attributing hostility to ambiguous actions. All of these work against innovation.

The second problem is that the biochemical stress triggers – cortisol, adrenaline, norepinephrine – cause problems when they are present for long periods of time. The stress response is literally poisonous over the long haul. This is called allostatic load. Humans, being the resilient and adaptable creatures that we are, can learn to live with high amounts of long-term allostatic load, but not without experiencing physical, emotional and cognitive downsides.

There is clearly a place that provides the benefits of challenge without the downsides of nervous system shutdown. This sweet spot prepares us for managing complex systems: we are best positioned to manage the unknown skillfully when we are neither complacent nor panicked. Larry Page, Google’s co-founder and Alphabet’s chief executive, calls this “uncomfortably excited.” It is also known as ‘flow.’ In my experience, there are three particular skills that can help you stay in that state.

Skill 1: Cultivate a different kind of executive information system

Every leader is familiar with the business truism that you can’t manage what you don’t measure, but how do you assess your physiological and mental responses to change and complexity? Many of us have fallen into the ‘boiling frog’ trap, where continual change and challenge gradually ratchet up our nervous system without us noticing. To become more cognizant of our status, we need to focus on a different suite of executive information – the signals provided by our bodies – and develop ways of assessing our level of fight-or-flight activation.

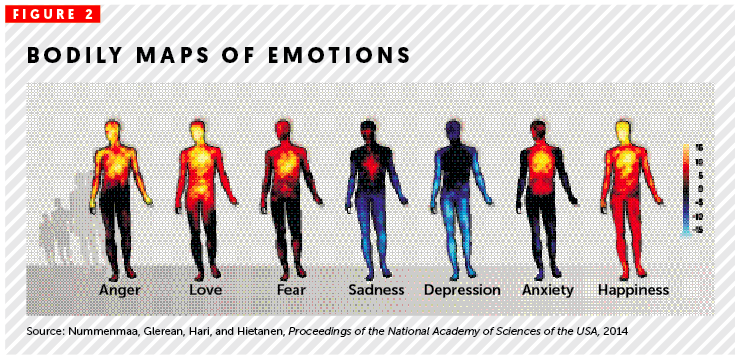

Our body is constantly giving us data. Each emotional state creates a corresponding sensation in the body. For example, when I’m angry, I feel heat in my cheeks, a tightness at the top of my throat and pressure in my chest. Researchers have mapped where people feel activation in their bodies, as Figure 2 shows (‘Bodily maps of emotions’, Nummenmaa, Glerean, Hari, and Hietanen, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 2014). Learning these signals is a powerful way of bringing awareness to your emotional state, which is critical, because the parts of the brain responsible for emotional body awareness are also the parts that work on emotional regulation.

So, the next time you’re feeling anxious or tightly wound, write down what sensations are appearing in your body. A dropping stomach or butterflies in the chest? That’s good data. When your ideas are flowing again and you feel connected to your team, note how this feels as well. Over time you will fine-tune your awareness of the information provided by your body. The sensations associated with stress are generally unpleasant, so it is natural to subconsciously train yourself to ignore and suppress them, living only from the ‘shoulders up’ – and men in particular have had deep cultural training in suppressing emotion, particularly in the workplace – but the first step in managing these feelings is to build awareness.

Self-awareness has limits, though. We can have blind spots, so it’s useful to develop external methods of checking your emotional state, by using relationships. Friends and family are a good early warning system. Peer groups, coaches and mentors can play a pivotal role too. Sharing your internal state can make you feel very vulnerable, so you may wish to consider peers either inside or outside your team, depending on your comfort level. Remember though, sharing can be liberating, bringing the realization that we’re not alone. Plus, nurturing these types of relationships creates deep trust and psychological safety – the most important aspects of team performance, according to Google research.

Skill 2: Regulate your stress response

When it comes to managing our stress response, it is a case of ‘manager, manager thyself.’ There are many ways to reduce stress. At Google, high performers who reported managing stress well credited their time with friends and family, exercise, sleep and meditation. The important thing is to choose the one that works for you – in that you note a decrease in perceived stress when you do it – and, most crucially, the one that you actually do. A meditation app that’s never opened, or a treadmill acting as an auxiliary wardrobe does not suffice! Experiment to see what works. And remember, although detaching from work may feel counterintuitive when you’re feeling ‘crunched’ by deadlines, regulating your stress or allostatic load is not ‘goofing off.’ You are increasing your capacity and ability to manage complexity.

As with self-awareness, self-regulation can be supported by the power of group and community. As a way of improving my consistency with meditation, I volunteered to lead a small sitting group at Google in meditating together. My skills were modest – little more than the ability to play a guided meditation and ring a bell – but I knew that if people were depending on me, I would keep up my intention to practice.

Time is always a constraint, so a successful strategy is to build stress-reduction into your routine. Try parking a little further from work to get in a walk and create time to reflect on your intentions for the day; or, do things as small as mindful walking while on the way to the bathroom, or using elevator time to meditate.

Skill 3: Be clear about your values

The world is complicated and getting more so by the minute. Values – our most important overarching priorities – provide a critical anchor. If we are unclear about what they are, we can make decisions we regret or that later trap us in difficult situations. One of the most difficult aspects of complexity is needing to make decisions that have multiple effects: some positive, and some potentially negative and hard to foresee. Our values provide a stable foundation for making those difficult choices.

As David Brooks noted in his 2015 New York Times piece ‘The Moral Bucket List,’ there are two types of virtues, or values: resume and eulogy values. Resume values can lead to short-term career achievement; eulogy values are those that we look back on and see as indicators of a life well lived. Developing eulogy values is truly the work of a lifetime, but it is trainable, and your daily job can be an avenue into this work. Look for workshops that provide a framework to think through your individual and group values, or simply block out time to reflect.

Your values can also be explored with a coach, peer groups, reading, and faith traditions. Developing values is a deeply personal process, and it is not simple – in complexity, you can expect there to be trade-offs between different values – but making time to articulate your values is essential.

We work in a world of constant, rapid and complex change. We need leaders with a calm, yet energetic response; who are ready to let go of the past, but remain rooted in strong values. Cultivating better self-awareness and the skills to regulate your stress response are critical steps towards being ready to lead in complexity.

— Bill Duane is a former engineering executive at Google. He is now principal at Bill Duane and Associates. This article first appeared on dialoguereview.com.