It’s one of the most misused concepts in learning and development. Byron Hanson makes the case for a rethink.

The ‘70/20/10’ concept is one of the most common concepts in employee development – and one of the most widely misunderstood. It captures the idea that effective workplace development includes different elements: the 70% denotes learning through experience on the job; the 20% represents learning through others; and the 10% represents development through programs, courses or content.

The model can be useful both for employees and HR departments, not least because it places emphasis on the value of learning through doing and dialogue, not just learning by knowing and understanding. However, I’ve seen many organizations run into problems in how the concept is translated into action, and how it can be leveraged to embed learning. It’s time for a few clarifications.

The time flaw

First, the 70/20/10 percentages do not relate to the actual time spent on development. In originally framing the concept, researchers asked employees how they had learned something related to their work: 70% of the time, respondents said it had been by doing it on the job, and so on. The model emerged not as a description of time spent, but of the percentage chance of a development activity sticking.

Yet employees are often instructed to base their development time around the 70/20/10 categories. This makes no sense. What if an up-and-coming manager wants to do an advanced qualification that requires weeks, or months, of coursework? How does that fit in the 10% time allotted? It may take pressure off HR departments and budgets to tell employees that most of their learning has to be “on the job,” but it is not an answer.

The ‘bucket’ problem

Another problem is the desire of many organizations to turn 70/20/10 into three buckets for development activities. I was recently working with one of the larger resource companies in Australia, and was shown their employee appraisal system. In the development section, employees had to list their planned development activities and objectives, using the three categories. Courses went into the 10% bucket; feedback, coaching or mentoring went into the 20% bucket; and finally, there was a list of all the things the employee would do at work. Each of the buckets had to have something.

These buckets may be good for HR systems, but the assumption that employee development can be separated out into distinct and potentially unaligned categories is faulty. Take Vanessa, a senior leader in that company. She had been identified as a high potential candidate for more senior roles. Her development plan consisted of a two-day course on executive presence and communication skills, mentoring from a senior female executive, and a stretch assignment working on a process improvement project. Each of these could be useful, but they can only be properly leveraged if the learning is integrated.

The 70/20/10 funnel

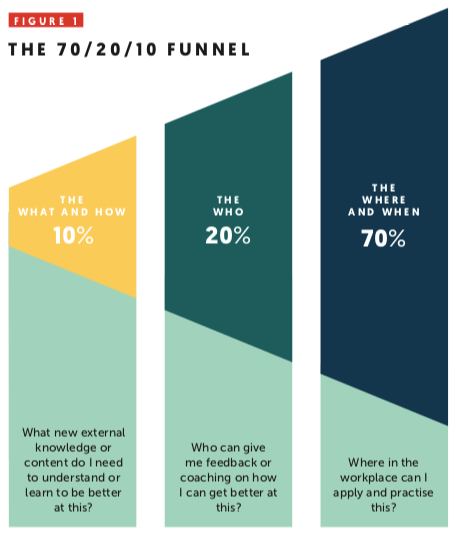

Employee development goals are more likely to be achieved when 70/20/10 is used as an integrated model. I describe this as a learning funnel. I like to use the model to set out areas of inquiry, beginning with the 10% and moving through to the 70%. This flow ensures that development activities are aligned.

So, before Vanessa does any development, it would be good to review what she is ‘missing’ in terms of her ability to do a more senior job. This may show she has nothing to learn externally, and the course she was going to take might be useless. But if she did take the course, its insights would be a natural agenda item for time spent in the 20% category. Vanessa’s mentor could bring a more aligned perspective and help extrapolate from new knowledge. Finally, the process improvement project would only be useful as a learning activity if Vanessa could use it to fill any skill gaps identified; otherwise, it may not stretch her as needed. If learning across the 70/20/10 categories is not integrated and aligned, the likeliness of embedding learning diminishes.

Unleashing the social system

A final critical point is that learning is social. If you want learning to stick, you must make it a team sport. We learn with others, not in isolation, yet 70/20/10 is typically represented as an individual development tool. My research in embedded learning suggests we need to unleash the social system in organizations to fully leverage the 70/20/10 concept.

The social system comprises the relationships and connections with critical stakeholders who leaders engage with in order to achieve objectives and get work done; it is made up of local ‘tribes,’ the groups a leader works with. Embedding learning means consciously engaging with the social system in three ways.

1 Context and meaning-making. I can’t apply new learning on the job unless I am clear about what it will mean for people around me and how my learning will play out in our context.

2 Application. If I do something new, I need to let those around me know what to expect and how it will impact their world.

3 Feedback. I won’t know if I am improving if I don’t receive fast and frequent feedback from my local tribe.

How leaders engage their social system to embed learning is shifting. Recent research from Duke Corporate Education has noted that the arrival of learning platforms with social hub functionality has not only made content more accessible, but has provided new mechanisms for leaders to connect, beyond traditional face-to-face interactions. This can make social learning and engagement more efficient: used well, these systems allow leaders to engage stakeholders faster and more frequently, helping to create connection in the moment, with real-time feedback on performance improvements.

Understanding that learning is social means that 70/20/10 cannot be done alone. Helping employees recognize how the social system can be leveraged is the critical missing link in ensuring that investment in development delivers improved competence at work.