Most leaders understand the importance of agility, but few actually prioritize the development of this crucial skill.

Agility pays: numerous international studies drawing on survey research, executive interviews, case studies, and financial analyses have proven conclusively that organizational agility leads to higher business performance. In fact, given the broad range of factors that can a ffect business success, it is striking how closely agility is linked to performance.

The return on agility

According to a global survey conducted by the UK magazine, The Economist, nine out of 10 executives believe organizational agility is critical to business success. This finding echoes that of a previous survey conducted by McKinsey (2010). The McKinsey study also found that executives around the world believe that, in the 21st century’s turbulent business environment, agility results in faster time to market, improved operating e efficiency, more satisfied customers and employees, as well as higher revenues.

These executives are onto something. A detailed international study sponsored by the American Management Association (AMA) also came up with two findings especially worth noting. While environmental turbulence makes it more difficult to compete and grow profits, companies with higher levels of agility have a distinct competitive advantage that leads to higher profitability. The AMA study found that organizational “resilience”, a related adaptive capacity, which correlates highly with agility, contributes significantly to business performance in turbulent environments. Resilience, as defined in this study, refers to an organization’s ability to resist, absorb, and respond to highly disruptive changes.

Challenging the assumption that “agile government agency” is an oxymoron, a global study conducted by AT Kearney and the London School of Economics discovered

that in the agile agencies they identified, productivity was 53% higher, employee satisfaction 38% higher, and customer (citizen) satisfaction 31% more than less agile agencies.

What’s going on? The agility imperative

Two deep, long-term trends – accelerating change and growing interdependence – have made agility a global imperative. Business has entered an era of fast-paced change. But what boggles the mind is that the pace of change is accelerating. In an increasingly unpredictable world, one thing we can confidently predict is that the pace of change will be faster next year and even faster the year after.

An equally important deep trend is increasing interdependence and complexity. With the advent of modern communication technologies and economic globalization, everything is becoming more interconnected. Customer and supplier relationships – and business partnerships – are more important than ever before. As a result, firms are struggling to overcome silos and increase effective collaboration within and between organizations.

Agility is not simply about speeding up in response to rapid change. Whether applied to organizations, teams or individual leaders, it is the ability to take sustained effective action amid conditions of accelerating change and mounting complexity.

How are we doing? The agility gap

In spite of the clear benefits of increased agility, the aforementioned Economist study found executives less than enthusiastic about agility levels in their own companies. The pace of change and degree of complexity in the business environment has jumped to a whole new level – and everyone is scrambling to catch up.

Interestingly, the Economist study also asked about the key obstacles to organizational agility. If it is such a powerful lever for increasing business performance, why is there such a gap? Executives mentioned organizational structures and processes, as well as IT systems. But one factor stood out above all others: the biggest barriers to increased agility lie in the organizational culture.

To better understand these obstacles and how to overcome them, additional studies focused on the role played by the “leadership culture”, that part of the corporate culture that sets norms and expectations for effective leadership. Several clear findings emerged: companies whose leaders operate at higher levels of agility are more agile as organizations. These studies also confirmed that increased organizational agility correlates with better business performance. These were the conclusions of a study conducted by ChangeWise, a US consulting

and training firm, in partnership with the Institute for Corporate Productivity, a US firm that researches practices associated with high performance. Half of the survey respondents were in global or multinational companies. The same findings were replicated in a subsequent study conducted by ChangeWise and the Swedish consulting firm, PsyCons.

What is leadership agility?

Given these findings, it is not surprising that, according to another global survey, senior executives rank agility at the top of the leadership capacities needed for business success. But what exactly is leadership agility and how do leaders put it into practice in the workplace?

A five-year investigation of this topic by ChangeWise, published in Leadership Agility (Joiner and Josephs, 2007), reveals that, at its core, leadership agility is the ability to take “reflective action” – to step back from one’s current focus, gain a broader, deeper perspective, then refocus and take action that is informed by this larger perspective. As leaders become more agile, their capacity for stepping back deepens and broadens, and the frequency with which they move through cycles of reflection and action increases. Agile leadership, then, is not just another tool for a manager’s tool kit. It is a core capacity, a “metacompetency,” if you will, that affects how leaders deploy all their other competencies.

To better understand how leadership agility plays out in specific leadership contexts, the researchers used questionnaires, in-depth interviews, on-site observations, client case studies and manager journals to examine the thought patterns, behaviour and performance of 600 managers across a range of industries, functions and organizational levels. The study found the leaders who are most successful in turbulent environments are skilled in exercising four mutually reinforcing types of agility:

• Context-setting agility: A leader’s willingness and ability to undertake initiatives that are strategic or even visionary, rather than simply tactical and incremental.

• Stakeholder agility: How effectively a leader understands key stakeholders and creates alignment with those whose views, priorities and objectives differ from their own.

• Creative agility: How insightful and creative a leader is when analyzing and solving the complex, novel problems generated in turbulent business environments.

• Self-leadership agility: How proactive a leader is in seeking feedback and in experimenting with new and more effective behaviours.

Leadership agility goes considerably beyond the now-popular term “learning agility”, a construct based on research originally conducted in the 1990s, looking at managers who adapted well to new assignments. Learning agility is similar to self-leadership agility, which also refers to a manager’s ability to learn from experience and apply these learnings, although not only in first time conditions. The other three types of leadership agility go beyond the ability to learn from experience, focusing on direct applications of agility, while framing and carrying out leadership initiatives.

Levels of leadership agility

The ChangeWise research took the view that, as the business environment becomes more challenging, competency-based leadership models need to be supplemented with a more dynamic approach emphasizing “vertical” adult development. Vertical development refers to a robust body of research that reveals how the “meaning-making” capacity of adults broadens and deepens through a series of distinct developmental stages. In adults, these stages do not refer to age-based life phases, but rather to the development of successive levels of cognitive capacity and emotional intelligence (see Ego Development by Jane Loevinger and The Evolving Self by Robert Kegan).

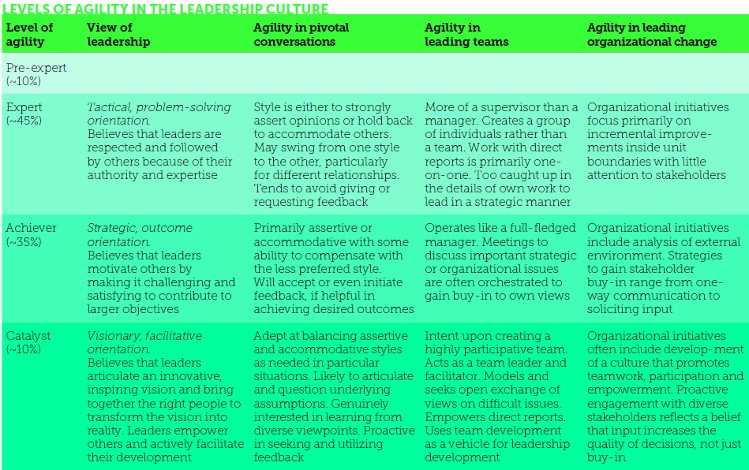

Central to the ChangeWise study was this question: how do leaders at different developmental stages think and act when leading change, leading teams and in pivotal conversations? The researchers not only identified distinctively different leadership behaviours that correlate with each stage, they also clarified the cognitive and emotional capacities that enable these behaviours. They called the combination of internal capacities and leadership behaviour found at each stage a “level of leadership agility”. A highly condensed summary of three key agility levels is provided in the table opposite.

Leadership agility levels are not personality types or thinking styles, like those assessed by the Myers Briggs Type Inventory or William Marston’s DISC theory. Instead, they are sequential stages in a leader’s development.

About 10% of managers are at the pre-expert stage, 45% at expert and 35% at achiever. Only about 10% have developed the cognitive and emotional capacities needed to lead at the catalyst level.

Think of these levels as being like nested Russian dolls: each level of leadership agility includes and goes beyond the skills and capacities developed at previous levels. Managers who have fully developed a catalyst “body” of practice still have their “inner achiever” and “inner expert,” allowing them to take action at any of these three levels, depending on what the situation requires.

The ChangeWise research reveals that managers who have developed catalyst-level leadership capacities are much more effective than those limited to the expert or achiever levels. Especially in developed economies, where expert-achiever leadership has been the norm for decades, companies face the historic challenge of developing their managers’ leadership agility to a whole new level. This research provides a “road map” that helps clarify what this catalyst level of leadership looks like in practice.

Levels of agility in the leadership culture

To envision the development of leadership agility on an organizational scale, it is useful to identify the agility levels that set the tone in a company’s leadership culture, realizing that different levels of agility may predominate at different managerial tiers:

• In an expert leadership culture, managers tend to operate within silos with little emphasis on cross-functional teamwork. Organizational improvements are mainly tactical and incremental. Managers tend to be overly involved in their subordinates work, often fighting fires and interacting with direct reports one-on-one. As a result, managers have little time to approach their own role strategically.

• In an achiever leadership culture, managers articulate strategic objectives and make sure they have the right people and processes in place to achieve them. This is a culture that encourages and rewards customer-focused, cross-functional team work. Change initiatives typically reflect an analysis of the larger environment, and consultation with key stakeholders is a cultural norm. Leaders try to minimize micro-managing. Instead, they work to develop effective teams and hold people accountable for achieving outcomes.

• A catalyst leadership culture focuses on achieving strategic outcomes, but it is animated by strong norms that support high participation, mutual trust, collaboration, creativity and straight talk. Senior teams become living laboratories that create this kind of culture within the team then work together to promote and encourage it in the organization they lead. Leaders not only coach their people, they actively solicit and utilize informal feedback about their own effectiveness as leaders.

Quite frequently, especially in the developed world, the executive tiers of management embody an achiever leadership culture, while an expert leadership culture predominates in the middle management ranks. A sprinkling of catalyst leaders may be found here and there in the organization. These leaders can have a powerful impact on organizational agility and business performance. But the development of a true catalyst culture in the executive ranks is a transformational journey of historical proportions.

Transforming leadership cultures

Through in-depth study of how catalyst executives lead organizations, lead senior teams and engage in pivotal conversations, we know a great deal about what a catalyst leadership culture looks like in action at the executive levels. It begins with a particular kind of vision for the organization that includes, and goes beyond, the achiever’s focus on strategic business outcomes.

Like achievers, catalyst leaders expand their thinking beyond current markets, products and services to anticipate new market developments and emerging business opportunities. But they are also committed to a longer-term vision: building an organization that is agile enough to sustain itself in the largely unknown future that lies beyond the current strategic horizon. While seeding business options for the long-range future, they set out to create an organization capable of continuously sensing and responding to unexpected disruptive developments that, in a highly unpredictable environment, often cannot be anticipated well in advance.

Integral to the catalyst’s business vision, then, is the vision of an agile, sustainable organization that, when realized, could be benchmarked by companies in any industry. Without ignoring performance issues, catalyst executives are alert to the positive potential that lies within people and the organization as a whole. They believe the path towards realizing this potential lies in the development of a culture with highly participative, empowering – and decisive – leadership at all levels. Genuinely interested in a diverse range of ideas and perspectives, they go out of their way to foster an environment that encourages innovative thinking and creative problem-solving – a culture where candid, constructive conversation and collaboration across boundaries are the norm.

One Canadian oil company executive called this “aiming through the target”, as in archery or karate. When promoted to president of the corporation’s refining and retailing division, it had just gone public and urgently needed a $5 increase in share price. But the firm he inherited was an average player in a crowded, mature, margin-sensitive market. Earnings were going steadily downhill and morale was at an all-time low. What he aimed for, beyond the target (share price), was the development of a catalyst culture. Like other catalyst leaders, he believed that, by moving along this path, the organization would benefit both short and long term. Within three years, annual earnings grew from $9 million to $40 million and cash expenses were reduced by $40 million a year. It became one of the most efficient and effective refiners in North America and one of the top retailers in its marketplace. Once shunned by investors, the business press pronounced it one of the darlings of the stock market.

To initiate this transformative change in the organizational culture, catalyst executives start by developing it within their senior team. They recognize that, for such fundamental change to become real, it cannot just be “rolled out” into the organization. It first needs to become a reality within their team. Like achievers, catalyst executives focus on the vital strategic work that needs to be done by any senior team. The key difference is that they accomplish this work by setting the context for robust dialogue and continually encouraging everyone to participate fully, while expressing genuine curiosity and openness to alternative perspectives.

Through the vision, facilitation and coaching of the catalyst leader, team members adopt a strong sense of responsibility that extends beyond their individual silos to the organization as a whole. They develop a sense of mutual trust and confidence in their ability to respond to vital business opportunities and solve tough organizational problems.

Over time, as change within teams becomes real, its members bring this new approach to leadership to their own teams. They also work together to create an organization devoted to continuous improvement, not only of its products, services and business processes, but also of its “human systems” – its people, its relationships with customers and other key stakeholders, and the organizational culture that underlies everything else.

Much of a leader’s most important work happens in pivotal conversations. In this crucial arena, catalyst leaders are equally at home advocating their own views and inviting others to challenge them. They seek others’ input not simply to get buy-in to their own views, but because they find they make better decisions when they consider alternative views and look for realistic win-win opportunities. These conversational capacities and skills are an essential part of the catalyst leader’s repertoire. Without them, they could not model the kind of culture they seek to create.

At its core, the transformation from achiever to catalyst leadership is about developing an intensified awareness and a broader, deeper intent or sense of purpose as a leader. Achiever leadership is rooted in a robust reflective capacity that allows managers to assess their own strengths and limitations. By thinking about how they led yesterday’s meeting, they can do a better job in future meetings. Catalyst leaders build on this reflective capacity by actively cultivating an ability to step back “in the moment”. For example, they can step back while leading a meeting and attend to assumptions, feelings, and behaviours that would otherwise escape their conscious awareness – then use these insights to make course corrections on the spot.

The underlying intent of achiever leaders is to achieve desired outcomes so they can make important contributions to the organizations and disciplines with which they identify. Catalyst leaders add a broader, deeper intent: to develop organizations, teams and relationships that are meaningful and satisfying, and that enable the sustained achievement of desired outcomes. This intent pervades how leaders at this level of agility approach everything they do.

The key to the achiever-catalyst transformation lies in making catalyst-level reflective action a regular practice. This means repeatedly re-activating catalyst intent, while experimenting toward the previously described catalyst leadership behaviours. It also means actively seeking feedback about one’s effectiveness as a leader, letting go of punitive self-consciousness and self-criticism, and becoming genuinely curious about how one is thinking, feeling and behaving while taking action.

In summary, from the research referenced in this article, and from accompanying leaders and organizations working on this transformation, a clear “through-line” can be seen that runs from deeper, broader intent and awareness, to more agile leadership behaviour, and on to increased organizational agility and higher levels of business performance.

Bill Joiner is president of ChangeWise, and a member of Duke CE’s global educator network.

An adapted version of this article appeared on the Dialogue Review website.

Illustrations: Mike Brooker-Jones