John Davis describes how effective brands create trust by catering to local markets

“It takes many good deeds to build a good reputation, and only one bad one to lose it,”

said Benjamin Franklin, founding father of the United States, more than 200 years ago.

His words are still relevant to global business today.

But what is reputation?

Reputation

=

Global brand

+

Local brand

–

Disconnects

Too few of today’s organizations and leaders are disciplined enough to live this every day. They don’t realize that a reputation and a brand are one and the same.

The good news is that this can be fixed by recognizing that reputation development drives brand strategy. Reputation and trust are synonymous (see ‘Brand of Gold’, Dialogue, Q1 2018), and leaders have an obligation to nurture trust both internally and externally. It cannot be manufactured, or situational. It must be consistently experienced.

The key to building a global reputation and being relevant in local markets, minimizing disconnects, is to embrace a ‘firm brand, loosely held’ approach, on the premise that a brand is guided by a universal set of principles, translated to regional locations based on cultural sensibilities.

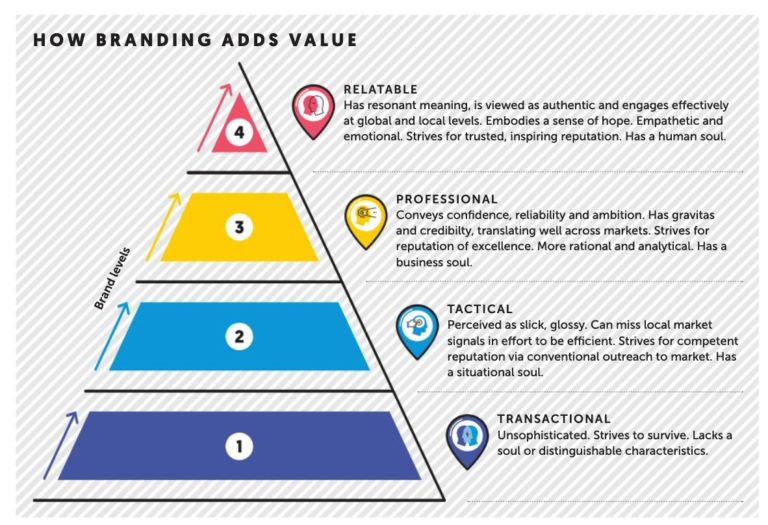

Competitive success

In my book Competitive Success – How Branding Adds Value, I looked at 500 top performing brands to understand how the best cultivated successful global and local reputations. Four brand levels emerged from the research (see page 30). Levels 3 and 4 represent the most successful brands, with the biggest struggles being faced by organizations at levels 1 or 2. Level 3 brands are Professional: for example, consulting firms. Level 4 brands are relatable, and are viewed as more human: Richard Branson’s Virgin brands embody this spirit. At both level 3 and 4, brands are clear about who and what they represent. Their reputations are built through the firm brand, loosely held approach.

Unfortunately, too many companies are still structured on last century’s business model, with leaders defining brand management as a systematic way of managing their firm’s image by hard-coating branding and using conventional marketing communications. This approach is obsolete, unimaginative and, as research shows, sows distrust with today’s customers. Top brands deliberately avoid being robotic and systematic, focusing instead on developing an organization that lives and breathes the brand. To paraphrase many of the comments from leaders I interviewed: “We meet people from top brands every day and they exude branding in everything they do. How can I get my organization to be like this?”

Put differently, these leaders are asking how they can humanize their brand. In a 2018 New York Times article, Amanda Hess said branding is a process that “imbues companies with personalities… A company with a soul becomes relatable”. But there is the potential for significant disconnects between attempts to humanize a brand’s personality and how the company operates day-to-day. Minimizing those disconnects requires more than slick marketing. The organization must be deeply connected through a myriad of formal and informal relationships that are observed, felt, and shaped by people within. Commanding and controlling the various reputation levers is impractical. The market owns control: leaders can only influence, not coerce or attempt to control, outcomes, by building strong networks of influencers. The organization’s brand and people’s experience with it, both inside the organization and outside, must be synonymous.

Brand inside = brand outside

It is critical to recognise that brand inside = brand outside. How you treat employees influences how they represent the brand which, in turn, impacts market perceptions. Rigid, top-down brand control is replaced by the bottom-up flexibility to tailor the brand’s core principles to local conditions and social norms, recognizing that any misalignment risks a disconnect that can harm reputation.

Internal/external misalignments are not the only branding risk, of course. Misunderstanding and miscommunicating to a local market can quickly create a damaging backlash. The examples, unfortunately, are legion.

In 2018 Heineken ran a TV commercial showing a bartender sliding a beer to a lighter skinned customer, passing three darker skinned people as it slid past, with the tag line ‘Sometimes, lighter is better’. Understandably, this ad stirred outrage and charges of racism.

Italian luxury fashion firm Dolce & Gabbana generated anger when it ran a TV ad in China, showing a Chinese model eating a pizza with chopsticks. The cultural message was undeniably insensitive and it led to significant negative publicity worldwide. Alibaba, Suning and other e-commerce firms stopped selling D&G products, and several major Chinese celebrities boycotted the brand’s products.

General Motors (GM), meanwhile, found itself in hot water when it ran a Cadillac commercial claiming that hard-working Americans ‘deserve’ a Cadillac, while implying that those of other cultures are lazy and undeserving. While not mentioning specific countries by name, the message was clear. The market reacted negatively. Ford took advantage of the misstep, running a counter-ad that mocked GM by saying that only people with a conscience who want to do good deserve to drive a Ford Focus, an affordable all-electric vehicle.

Ask the right questions

Brand disconnects can undermine a firm’s reputation in minutes. Repairing the damage can take years. So what leads to these disconnects? To paraphrase the GM ad, laziness. The checks and balances required to ensure that a brand’s message is appropriate for a local context are not onerous, but not enough leaders ask the right questions:

- Do we understand the local market context?

- Are the messages we’re sending aligned with our values and principles?

- Is the communication appropriate for the market we’re entering?

Reputation is reinforced everyday by employees on the ground who have a far more informed and nuanced understanding of local context than their remote headquarters colleagues. Great global/local branding doesn’t regard uniformity or being frictionless as objectives. The best brands don’t insist on rigid conformity; regional offices can and do push back when brand initiatives lack local relevance. This is healthy friction, sharpening mutual understanding and signalling internal trust. Unhealthy friction, however, often results when global teams demand strict compliance, signalling their indifference to and disrespect for insights from local offices.

In top organizations, everyone owns the brand, so senior leaders are obliged to foster an atmosphere that allows local managers to call out branding that fails to reflect market context. That can be done by providing advance communication about overall brand strategy, by asking local managers if they detect any misalignments between the proposed branding and local conditions, and by supporting locally-led strategy execution.

Nestlé is a good example of understanding context. Their country-specific websites feature common worldwide themes followed by unique homepage messages, native languages and highlights of initiatives that resonate with local markets. The effort to combine a common global identify with local tailoring signals that Nestlé understands the importance of being contextually sensitive to its markets.

Don’t just measure, create meaning

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) can be counted. Our essential ‘humanness’ – our soft skills, our collaborative ability, our effort to empathize – cannot, yet no one would dispute their importance. As the old adage has it: “Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted.” In fact, my research found that KPIs are some of the biggest culprits behind reputation destruction. Over-emphasizing the importance of KPIs can disconnect a person’s performance from the larger organizational community, because KPIs can distort individual motivation. Creating a ‘results at all costs’ mentality can lead to reduced engagement from employees, even if financial targets are achieved.

To illustrate: a manufacturer in Asia had several consecutive years of impressive financial growth, yet internal engagement scores were declining each year. Although people were achieving their numbers, they were creating a toxic environment in the process, and the brand’s reputation was being damaged. It wasn’t until customers said they felt mistreated, and would leave if the company didn’t fix the problems, that action was taken. The company had to break a culture that was dominated by individual KPI-based performance management. It did so by creating collaborative performance objectives and new soft-skill, growth-mindset routines. New solutions began to emerge, financials continued to improve, and engagement scores started to reverse their decline.

The Four Seasons Hotels brand, meanwhile, is widely recognized for its world-class service, delivered uniquely in each market. During one visit, my family and I were greeted by name by the concierge as we entered the lobby. The front office manager also knew our names, including those of our children, who were each given a gift specific to their personality, making them eternally loyal to the hotel, much to my financial chagrin. It was a delightful example of creating a meaningful experience.

At the time, I was chief executive of a boutique hotel company and I wanted to learn their service secrets. The front office manager explained that the hotel creates guest profiles before check-in – in our case, using notes that the reservationist took during my call – before preparing welcome gifts. I asked her how they knew our names when we entered the lobby, since we weren’t wearing name badges. She said, “Oh, that’s easy. The valet looked at your luggage tags as you entered the lobby and then phoned the concierge to say that the Davis family – two adults, three kids – has arrived. The concierge hung up and walked over to you.”

It was simple, yet powerful. Four Seasons ensures its employees know the universal brand principles and are empowered to contextualize those principles locally, minimizing disconnects and thereby creating meaning for everyone.

Empowering people to build your reputation

Ultimately, empowerment and engagement among employees is pivotal to company growth and demand. Growth requires demand for your offerings; demand is spurred by market interest borne from reputation; and the quality of that reputation starts with the people inside the organization believing they are trusted, and understanding how their contributions affect stakeholders.

Command and control micromanagement of work habits and KPIs won’t create an inspired workplace. Employee and partner ecosystems thrive best when objectives, values and contribution to society are mutually reinforcing, not approached as zero-sum. Leaders must understand how their brand creates meaning for both employees and society, and nurture both workplace environments and partner ecosystems that are in sync with each other and with

market needs.

When aligned this way, brands not only build reputation and drive growth: they even have a credible and positive role to play as a force for good in the world, serving as a de facto decision-making filter when stakeholders are choosing among different value propositions. Leaders must think boldly about what makes their organization a distinctive force for good and recognize how their offerings are experienced.

It is not easy to build a successful brand. But when reputation and trust are the drivers, good deeds are bound to follow.

An adapted version of this article appeared on the Dialogue Review website.