It involves continuously unlearning and relearning.

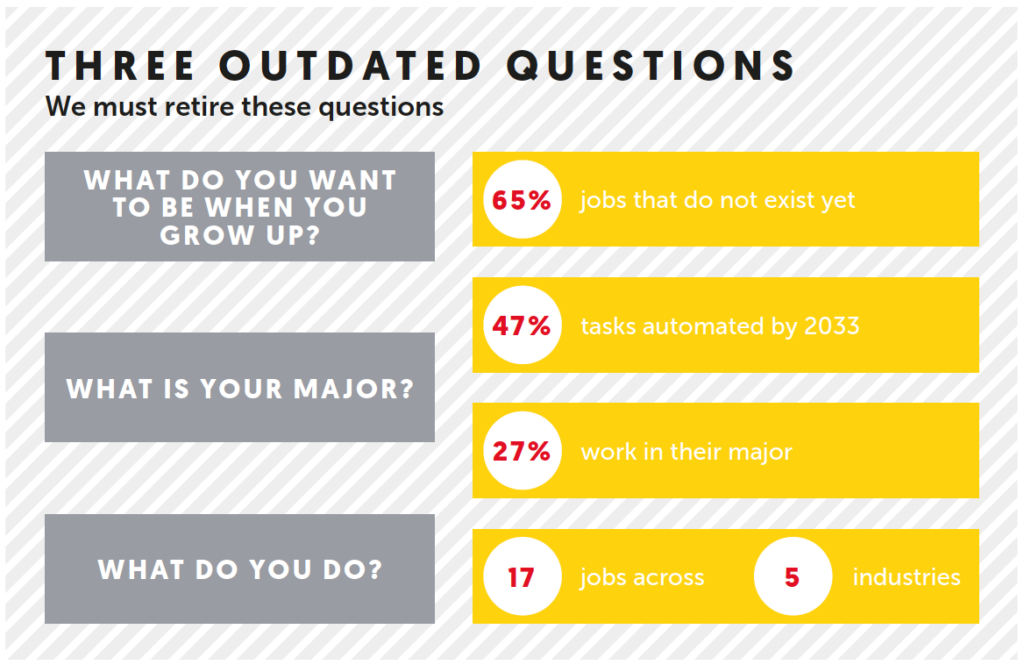

For generations, schools, universities, and workplaces have prepared citizens to work in a linear fashion. Identify necessary skills, devise a training curriculum or post-secondary program, transfer knowledge to potential workers, and – voilà – you have a workforce prepared to answer any number of specific demands in the market.

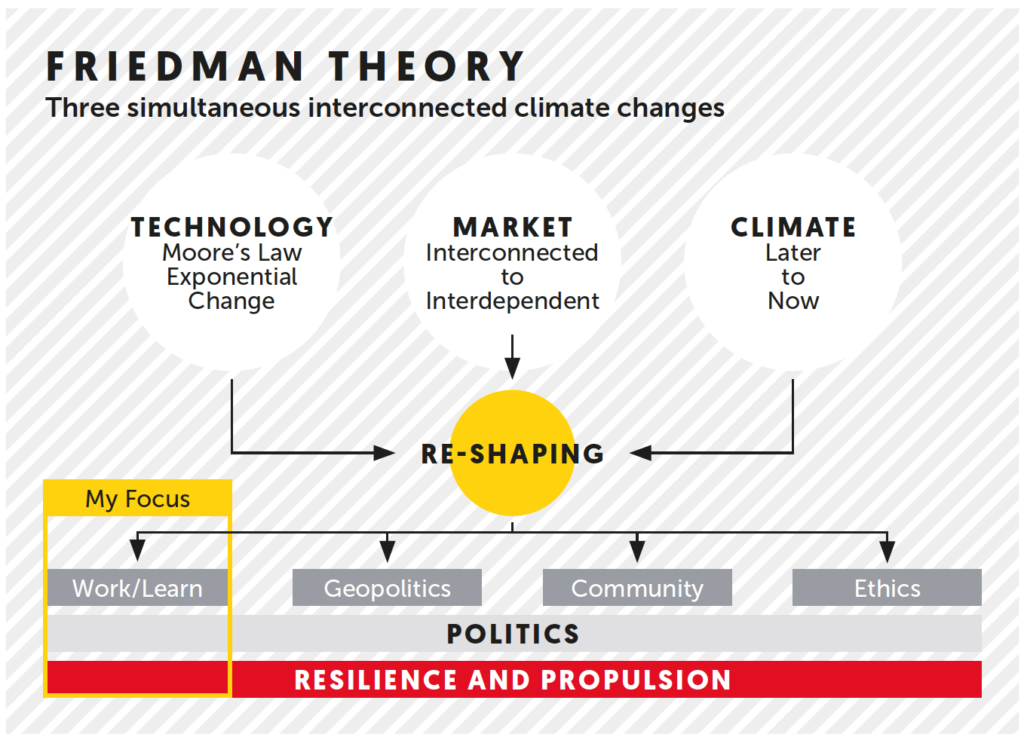

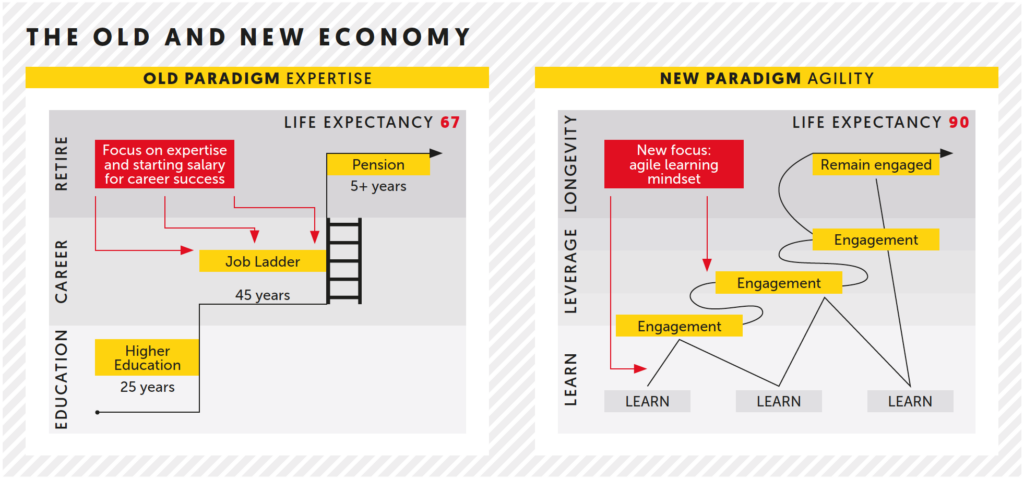

This model worked well when change came slowly. Businesses could forecast future needs reasonably accurately, and students could train to fill those needs with assurance that a good job would reward focused academic preparation. No more. The rate of change is simply too swift. Where once an economic paradigm shift could be absorbed over multiple generations – consider the shift from agriculture to manufacturing work – we can now expect to absorb multiple shifts in a single lifetime. We have arrived at the Age of Accelerations, as New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman’s theory has it.

The Age of Accelerations comprises three exponential growth and change trends: technology (Moore’s Law), the market (interdependent global markets), and the climate (climate change, biodiversity loss, population growth). Technology is measured by the relentless march of Moore’s Law, which has delivered computing power at low enough cost that now anything mentally routine or predictable – perhaps half of all work – can be replaced by technology. The market has moved from being connected, to hyper-connected, to interdependent – forcing failures and successes to be absorbed by all. Climate change not only drives shifts in energy markets (driving down the cost of solar to compete with cheap coal, for example), but also changes in human migration, as super storms, drought, and other conditions drive people from their homelands to seek safety and economic advantage elsewhere. Friedman argues that these three interlocking accelerations are redefining geopolitics, politics, community, ethics and –perhaps most of all – learning and work. Change runs blindingly fast up an exponential curve, demanding that we think differently about work and learning.

That single dose of education stockpiled in our twenties will barely last into our thirties. And that 40-year career arc is stretching to 50 or more years, as we live longer, healthier, and more engaged lives. Where we once jumped on the career ladder and climbed to retirement, workers now navigate a complex maze of ever-changing possibilities. Traversing this maze will require not just stored knowledge and experience, but a flexible and ready ability to learn, adapt, collaborate and create.

Corporations become learning leaders: the shift from scalable production to scalable learning

Where the academy once sat at the centre of learning, corporations must now move into that pivotal position. John Hagel, who leads Deloitte’s Center for the Edge, raised the alarm to corporate leaders that the Age of Acceleration required a fundamental shift in business objectives, one he describes as the move from scalable business to scalable learning. In short, it will be far more important for a business to rapidly and continuously learn and adapt than it will be to push more product through a cheaper pipeline.

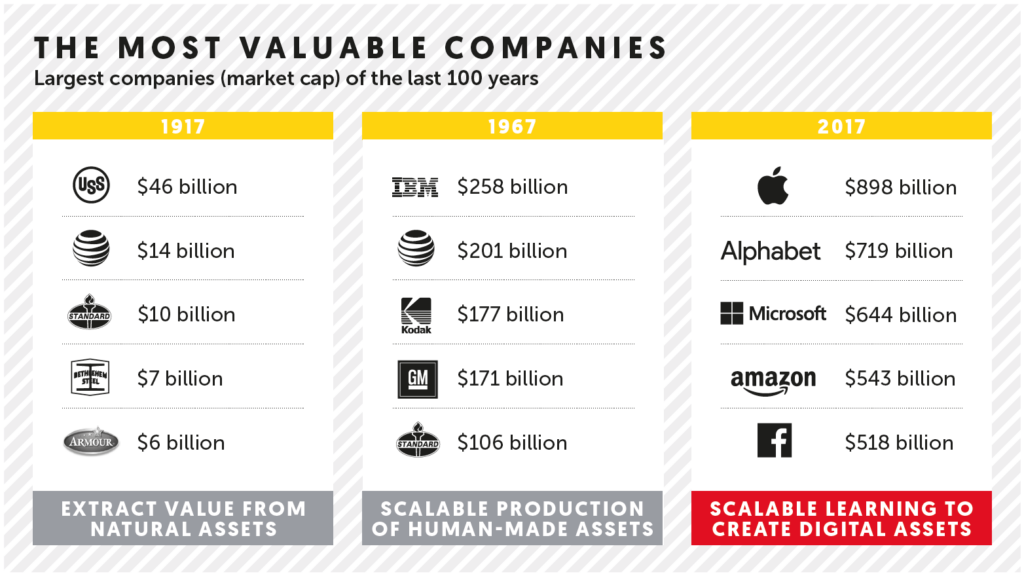

The impact of Hagel’s directive becomes clear when we look at the five most valued US companies by market capitalization, past and present. One hundred years ago, the most valuable companies created wealth by extracting value from natural resources. Think steel, oil, gas and meat production companies. To succeed in these markets, these companies need access to capital.

Fifty years ago, the most valuable companies were automotive, telecommunications and chemical companies that scaled production capabilities with skilled labour. This shift toward production of manmade goods in the post-war era drove people en masse to seek higher education, filling the pipeline from classroom to factory with workers trained to specific roles.

Today, our most valuable companies create and leverage digital technology. These companies create value by learning faster than the competition. Every product or service offered is merely a data collection vehicle from which to learn more about the customer. We believe, at its core, every product or service is simply the exhaust from a learning exercise.

As we dive headlong into the future, a worker’s capacity for learning will be the fundamental skill since any routine or predictable task will be delegated to an algorithm. So how does an organization screen, develop and organize its workforce to meet this emerging challenge? Enter the moonshot.

The moonshot mindset

When John F Kennedy challenged his country to send a man to the moon, NASA was unable to just go out and hire an experienced moon-walker. Indeed, the parade of ‘firsts’ needed to realize the challenge meant that NASA had to rely on capacity and capability, rather than experience, to build the infrastructure, machinery and programmes that would send a man to the moon. Just as importantly, the programme assembled collaborative teams across disciplines and organizations in order to first figure out what had to be done, and then do it. In other words, the questions emerged in concert with the answers, and often the answers suggested researchers were asking the wrong questions. Navigating so many unknowns required a nimbleness of thought and real learning agility.

Today, business finds itself in a new era of economic productivity defined, in part, by rapid change and technology-driven creative destruction and reinvention. Like NASA, business can’t depend on experience to develop and exploit new opportunities. To tackle the ‘firsts’ that will present themselves in the Age of Acceleration, businesses must build learning agility into their organizations. Companies must continually adapt and upskill capabilities so they can discover and deliver new products and services.

We need to think differently; we need a north star and a handrail to the future. Enter purpose and culture.

The purposeful business

In the swirl of accelerated change, a strong culture holds the centre of any organization. Too often lumped into a pile with employee benefits or workplace perks, culture is the operating system of every organization. With a clear sense of purpose, clarity of values, and well-articulated operating principles, businesses can sustain disruptions, reinventing themselves to take on new challenges.

Leaders ready to take on the Age of Acceleration need to shift their focus from the outputs of an entity – the brand and products – to the inputs, namely culture and capacity. Culture is an expression of the brand and product (or services) is the evidence of capacity. In the Age of Acceleration, a product or service – or any value created by the entity – is merely evidence of the company’s learning. Companies that will thrive in the Age of Acceleration focus on nurturing their culture and increasing their capacity by continually expanding and upgrading their capabilities. Capacity-focused leaders hire workers for their cultural and purpose alignment, learning agility and workplace adaptability. To attract capacity-matched workers, organizations must lead with their purpose and make clear their culture principles, and they must hold to these truths.

It is interesting to note that while freelance or gig workers are often perceived as lesser contributors to organizations than employees, the opposite may be true. An extensive study, Freelancing in America 2017 by Edelman Intelligence, found that not only do full-time freelancers feel their work is already impacted by rising automation (49% for freelancers vs. 18% for full-time employees), 65% of full-time freelancers report they invest regularly in updating their skills vs. 45% of full-time employees.

As the Institute For the Future’s Marina Gorbis proposed, “As we close the digital divide, the next divide to emerge will be the motivational drive. Those motivated to continuously learn and adapt will thrive.”

This is a tectonic shift in identity from external validation (for example, a degree or a job title) to internal validation, tapping into intrinsic motivations to learn and adapt for life in pursuit of our aspirational selves. Studies have shown that recovery from a job loss today can take twice as long as the grieving period for the loss of a spouse. This indicates a vulnerable sense of self subject to the whims of the market. We see a brighter, more adaptive and resilient future by tapping into internal motivation and passion.

How to do it

Few dispute the increasing rapidity of change, and the impact of that change on jobs and the future of work. A focus on trends in the gig-economy or retooling with robots is too narrow an answer. Here are four things you can do now to build a foundation for the future of work.

1. Be deliberate about culture and purpose

Every company has a culture, often not well-articulated. Take time to examine your organization, and document your purpose and your operating principles. Ask:

- Why do we exist?

- How is the world different/better because we exist?

- What will we do – and as importantly, not do – to achieve our purpose?

- How will we process and learn from failure?

- How do we acknowledge and celebrate success?

As you explore the answers to these questions, test them with colleagues at every level of the business. And then act on those beliefs. This is not a one-time or annual discussion; culture requires daily nurturing. Make a habit of framing tough decisions and difficult conversations through the lens of culture and purpose.

2. Identify your personal purpose and passions as a leader and team

Just as you document the culture of your organization, document the culture of your career. What do you value in yourself and your relationships with co-workers? What makes work worthwhile? How do you want to be evaluated by others? Which values do you bring to your work? Think of this as a sort of ‘operating manual’ for your work, explicitly stating your preferences in work style and in interaction with co-workers.

Once documented, discuss them with your team and encourage every team member to create an operating manual for themselves.

This exercise is the first step toward creating alignment that runs through the workforce, your leadership, and ultimately to the company’s purpose. It may lead to hard decisions if it uncovers poor alignment in some people or areas.

3. End every major project with a postmortem

Most businesses do postmortems all wrong. They quickly dismiss all that went well, then berate themselves (or worse, each other) over what went wrong. They promise to do better next time, then quickly fall back into business as usual. A learning postmortem looks at a project differently. It asks:

- What happened that we did not expect?

- What did we learn from that experience?

- What were the unexpected successes and how will they affect our future practices?

- What were the unexpected failures and how will they affect our future practices?

- What did you discover about your colleagues during this project?

- Which knowledge obstacles did we need to overcome? How did we do that? And what will that enable us to do in the future?

- Based on the experience with this project, what are we now prepared to do?

4. Institutionalize learning

Make learning an explicit goal of your organization and build learning into your organizational practices. For example, you might organize your teams around ‘learning tours’ that use work assignments to give your team exposure to different parts of the organization. Learning tours move individuals around the company in a manner that institutionalizes learning-as-outcome.

Add collaborative learning days into your company calendar. Set a challenge for work teams to develop, prototype and present a new product/service concept in a single work day. Don’t expect to identify your next billion-dollar line of business, but do watch, and have your employees report on, how these intense days spark new learning and insight.

Make talent discovery and sharing a part of your employee experience. Your people come to work as interesting and complex humans with many hidden talents. Use team meetings, ice-breakers, or explicit events as a means of drawing out these capabilities.

A learning culture

Building a learning culture is a deliberate and ongoing process, and it only happens with leadership committed to putting learning front and centre. Develop a learning plan for your organization that includes employees, contractors, gig workers and partners alike. Where we once learned to work, now we will spend long careers working continuously to unlearn – and relearn.

— Heather McGowan and Chris Shipley are sought-after thought leaders in the education and technology innovation sectors www.futureislearning.com. Heather will elaborate on some of the points in this article during our next Duke CE Leadership Series complimentary webinar on November 28th at 11:00-11:45AM EST, 4:00-4:45 GMT. Register.

An adapted version of this article appeared on the Dialogue Review website.