The world is being transformed at an incredible pace. How will leaders respond to the megatrends that are shaping the 21st century?

Think back to what the world was like 25 years ago. In 1998, China was just starting to build its infrastructure. President Jiang Zemin and premier Zhu Rongji were busy dismantling state-owned enterprises and embracing the logic of the market. Boris Yeltsin was president of Russia, keen to integrate his country with the rest of the world. The World Trade Organization had just been established, with practically all the world’s leaders embracing free trade with gusto. The dumb mobile phone ruled the day, yet was in the hands of less than a quarter of all Americans. And artificial intelligence was just a technical curiosity.

How dramatically today’s world differs from that of 1998. Consider now that, in the next ten years, the world will change more than it has in the last 25. What are the megatrends reshaping the structure and dynamics of the global economy? How will they redefine the organizational features of global enterprises that hope to stay or emerge as the winners in the new era?

Global game changers

Among the multitude of forces pulling and pushing the global economy in various directions, we focus on the big five.

1. Asia moves to the world’s center

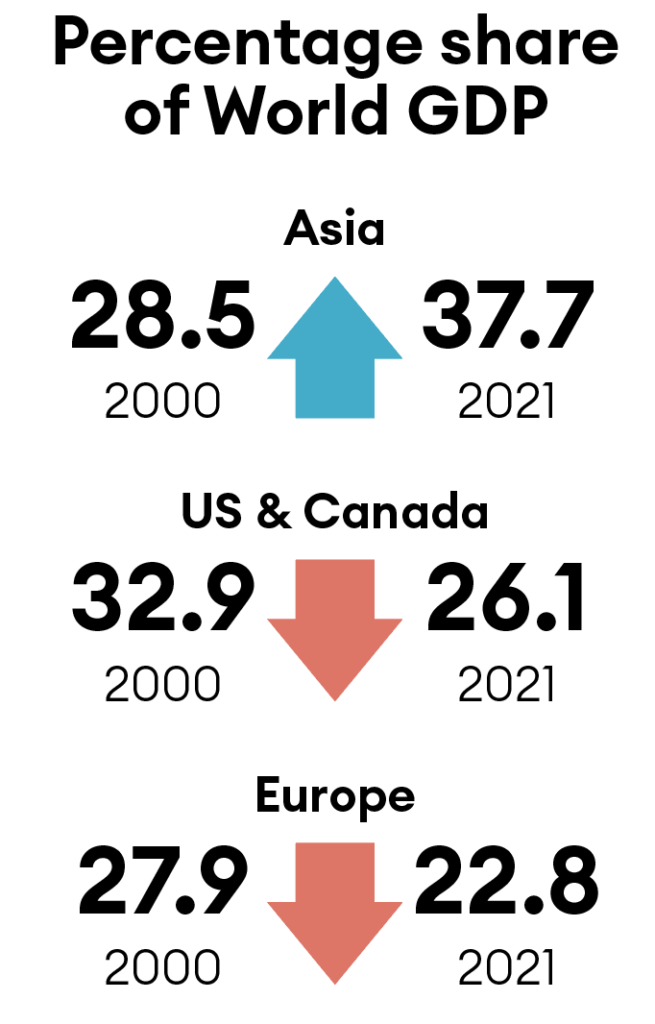

In 2000, North America, Europe and Asia accounted for 90% of the world’s economy, split roughly evenly across the three continents. Today, Asia’s share of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP) is 38% versus 26% for North America and 22% for Europe. In ten years, Asia’s GDP will likely equal that of the US and Europe combined.

Asia’s economic rise is being fueled by the fact that three of the world’s fastest growing large economic regions are all based in that continent – China, India and Southeast Asia. Given the slowdown in China, India is now the world’s fastest growing large economy. Currently the fifth largest, it will be the world’s third largest by 2028, according to IMF projections. While the US will remain the world’s dominant economic and technological power for quite some time, the next three biggest economies will all be Asian – China, India and Japan.

2. A more contested world

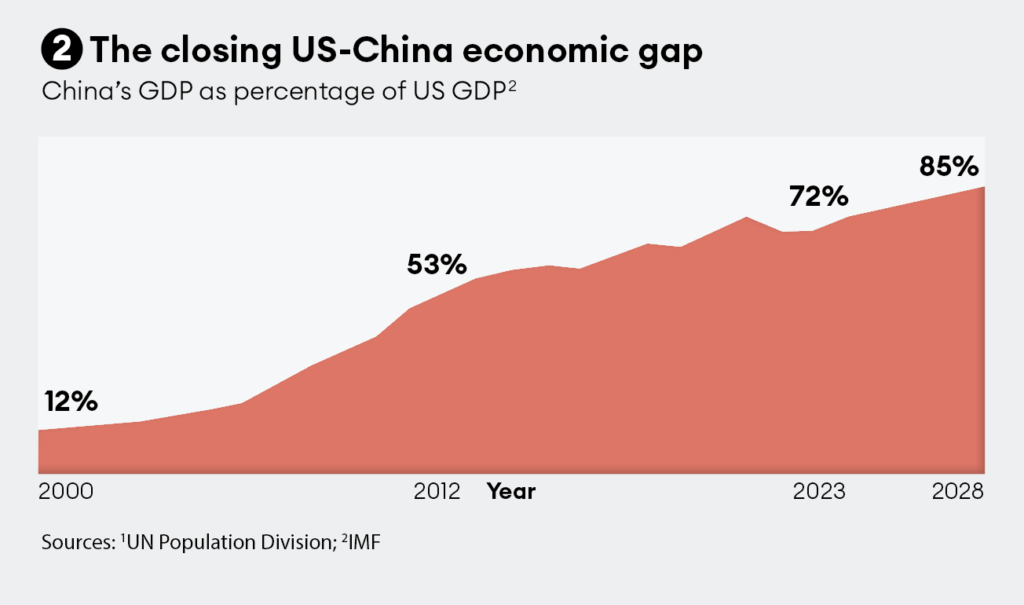

In 2000, China’s GDP was 12% of US GDP; today, it is 72%. The gap is closing, albeit much more slowly than in the past. President Xi Jinping has declared that his ambition is for China to supplant America and become the world’s most powerful nation. Given the geopolitical conflicts over Taiwan, the South China Sea, and East China Sea, the two countries are now locked in a new Cold War. Backed with clear bipartisan support, the US is engaged in an active economic and technological decoupling from China and is urging its allies to do the same.

Rising tensions between the US and China are not the only geopolitical challenges facing the world. China and India are trapped in a bitter territorial contest over their poorly demarcated 2,000-mile border. India and Pakistan have fought multiple wars and remain deadlocked over overlapping claims to Kashmir. North Korea remains a nuclear menace. And, with Russia’s aggression into Ukraine, we are now witness to the first major land war in Europe since World War II.

3. Crisis of global warming

More frequent occurrences of severe weather patterns everywhere are the concrete outcomes of the fact that the earth’s surface temperature has risen by 1.2oC over the last 150 years and could crack an even more dangerous 1.5oC level by 2040. Methane and carbon dioxide emissions are the two biggest culprits. Atmospheric CO2 concentrations have increased from 300 to 420 parts per million over the last century.

Global warming is the toxic side effect of an otherwise glorious development – faster economic growth in emerging economies, which account for 80% of the world’s population and over 40% of the world’s GDP. Until a decade ago, government officials in emerging economies used to argue that dealing with the climate crisis was something that only developed economies needed to worry about: the bulk of the CO2 in the atmosphere came from carbon emitted by developed economies over the last two centuries. The perspective now is different. Citizens in emerging economies suffer as much, if not more, from severe weather patterns. Unless emerging economies do their part as well, there can be no viable solution to the global problem.

Thankfully, entrepreneurs have responded to the climate crisis with powerful innovations such as solar and wind farms, electric vehicles, battery-based storage systems, and more energy-efficient buildings. These innovations also have implications for the structure of the global economy. While the world still consumes more oil, gas and coal each year, the fossil fuel intensity of the global economy is declining. As a direct result, global trade flows will depend less and less on shipments of bulk commodities such as oil, gas and coal.

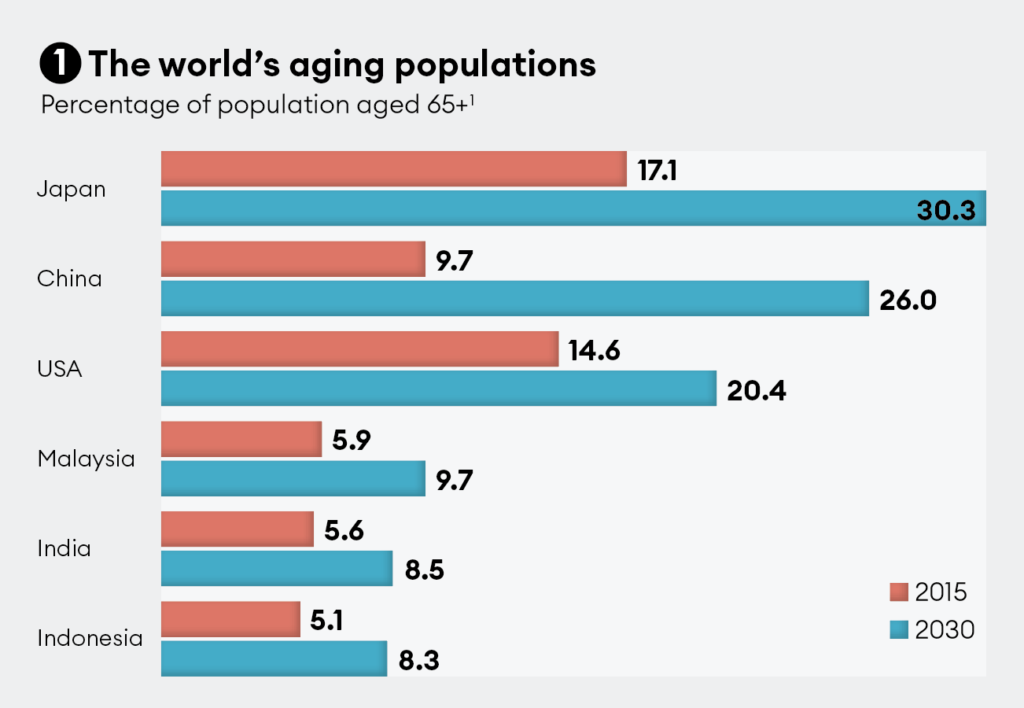

4. More gray hair

The world is aging rapidly. Since 1990, the world’s median age has jumped from 24 to 32. This too is a side effect of rapid economic growth in emerging economies. Irrespective of ethnicity or religious beliefs, when people become better off and more educated, they choose to have fewer children. Rapid aging is most intensely evident in Asia, the world’s fastest-growing economic region. The demographic challenges in China are particularly acute, owing to the disastrous long-term effects of the country’s one child policy. By 2030, 26% of China’s entire population will be 65 years of age or older.

Aging of the population creates several economic challenges. Health care and social security costs increase rapidly. At the same time, the size of the working-age population that can help grow the economy shrinks. Unless the elderly agree to delay the minimum retirement age, the only way out for governments is more debt and higher taxes. For developed economies, welcoming more immigrants from emerging economies would certainly help. Immigrants from the future (also called robots) could help as well.

5. Digitization of everything

Each passing day, virtually everything is becoming more digitized. Our factories, our business processes, our entertainment, our sports, our work, our meetings, our cars, our highways, our homes, our environment, our watches, our clothes and sneakers – even our bodies.

Digitization of everything, coupled with decline in commodities trade and shorter supply chains for manufactured goods, means that globalization – that is, cross-border integration among nations – is increasingly being defined by flows of bits and bytes rather than atoms. According to McKinsey, cross-border data flows are growing by 20% each year and already account for a bigger contribution to global GDP than trade in physical goods.

Strategic implications for global companies

Evolutionary theory tells us that, when the environment changes, organisms need to change as well. Otherwise, they wither and die. The outlines of what the above megatrends mean for global enterprises are already becoming clear.

Deepen your engagement with local ecosystems

Global scale remains important for global competitive advantage. As emerging economies scale up, no company – low-tech or high-tech – can hope to acquire the necessary scale without a deep commitment to win, not just in developed, but also in emerging markets.

Winning in large and intensely competitive markets is rarely possible without a deep commitment to and engagement with the local ecosystem, including the localization of a good chunk of the value chain. American companies discovered this early on in their battle for European and Japanese markets (and vice versa). This imperative is now becoming true for emerging markets as well. This is why Tesla has a giga factory in Shanghai, is building one in Mexico, and has signaled that its next giga factory after that could be in India.

Deeper engagement with local markets will require deeper market penetration in both urban as well as rural markets, localization of products and services, localization of production, much greater reliance on local talent, openness to local alliances, and deeper engagement with local stakeholders, such as the media and the government. Over time, these developments will mean that the global enterprise becomes more a federation of regional hubs than a centrally run monolith. As Enrique Lores, HP’s chief executive, remarked in a recent interview, “We’re going to go to a model that is going to be much more regional where there will be regional hubs both for manufacturing and, to some extent, design.”

De-risk your global supply chain

Growing geopolitical tensions mean that pure efficiency can no longer be the sole driver of how global supply chains are designed. Companies also need to factor in risks of disruption from government mandates or actual conflict. Depending on the product, the path to de-risking lies in an optimal combination of friend-shoring, near-shoring, and in-shoring.

As an example, take Apple which has historically concentrated the assembly of virtually all products in China. Working with manufacturing partners such as Foxconn, Apple is steadily but rapidly developing new global manufacturing hubs in India and Vietnam. Over the last year, India’s share of global iPhone production has grown from 2% to 7%. According to media reports, it is expected to hit 25% by 2025. Similarly, Apple has started diversifying the production of MacBooks from China to Vietnam.

Sustainability as a core plank in your strategy

Insurers are already starting to price in climate risks faced by companies. So are investors. The risks of ignoring environmental sustainability can only increase over time. Thus, companies must make sustainability an imperative in the design and management of every activity in the value chain – manufacturing, supply chain logistics, even office buildings. We are particularly impressed with Unilever’s efforts – what the company calls its Sustainable Living Plan – in this regard.

Given the growing awareness of the climate crisis among consumers, sustainability is also becoming an opportunity to increase the competitive advantage of the company’s products and services. Not surprisingly, in 2018, Unilever launched Omo EcoActive, a laundry detergent designed to deliver excellent cleaning performance while using less water and energy.

Look for the gold in the gray

An aging population is an economic challenge on a societal level, but also presents opportunities for companies. With the elderly accounting for a bigger proportion of the population, the demand for products and services that cater to their needs can be expected to grow at a faster pace than the overall economy. Pharma, retirement homes, in-home healthcare, robotic assistants and wealth management are some of the industry sectors that should be beneficiaries of the demographic changes under way.

A new China strategy: in-China-for-China

Companies with an already sizable market presence in China need to start compartmentalizing their China business from the rest of the global operations. Such a strategy would help the company stay committed to China while reducing the risks from potential adverse regulatory mandates from either China or the home country. A recent survey of 480 member companies by the EU Chamber of Commerce in China found that 27% of them had already started decoupling their Chinese operations from corporate headquarters.

Consider the German carmaker Volkswagen (VW). Starting in 2022, VW has invested over $2 billion in a partnership with Horizon Robotics, a Chinese software and chip maker focused on autonomous driving. According to a company statement, any technology developed by the joint venture will stay in China.

Optimize the management of digital assets

As we discussed earlier, for every company, the business value of digital assets is growing much faster than that of physical assets. Digital assets include software, digital platforms, product and process blueprints, data and AI algorithms. For the global enterprise, creating and managing digital assets requires paying attention to a number of questions.

- At which few locations in the world should the software and digital platforms be developed, maintained, and upgraded?

- Which few locations will be given the charter to develop global product blueprints? And process blueprints, e.g. regarding the design and management of factories?

- How will the company protect its intellectual property?

- How will the company make its software, digital platforms, and product and process blueprints accessible to and usable by dispersed local operations?

- How will the company ensure that its data collection and transfer processes do not fall foul of data privacy and sovereignty regulations?

- How will the company convert local data into global competitive advantage via the development of AI algorithms?

Organizations maximize their chances of survival when they mirror or adapt to changes in the external environment. The structure and dynamics of the global economy in 2030 will be dramatically different from those in 2010 or even 2020. Global enterprises that hope to stay or emerge as the winners in the new era must rethink and redesign almost all key aspects of their strategies and organizations. As the legendary Canadian ice-hockey champion Wayne Gretzky famously said: “Skate to where the puck is going, not where it has been.”

Anil K Gupta is the Michael Dingman chair in strategy and globalization at the University of Maryland. Haiyan Wang is managing partner of the China India Institute, a research and advisory organization.